Homage to Orwell

I took my copy of George Orwell: Essays off my bookshelf in Jerusalem once again this month, amid the global psychiatric episode triggered by the war against Hamas in Gaza. Here in the 1,400 pages of Essays is old Eric Blair with his hand-rolled cigarette and reedy voice, neck pocked by a fascist bullet and face prematurely lined, a blue worker’s shirt under a jacket of incongruously expensive tailoring, pressing on us his understanding of Communism, class, toads, dirty postcards, rampaging elephants, obscure ideological rifts, writers unjustly forgotten or wrongly celebrated, and books barely read even when they were new.

Orwell is best known for the antitotalitarian novels he wrote in the 1940s, Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, but his true genius lies in his journalism. Some of his predictions were completely wrong (“If we can hold out for a few more months,” he declared amid the German assault in 1940, “in a year’s time we’ll see red militias billeted in the Ritz”) and many of his topics no longer matter. But because he told the truth as he saw it and was not seduced by fashionable opinion, because he preferred people to ideas, and because of his incomparably clear and urgent style, it is Orwell more than any other modern writer who remains the compass for those who hope to describe a bewildering world in clear English.

“Bewildering” is certainly one way to describe a Western intellectual scene that has responded to a murderous rampage by religious fanatics against Jews on October 7, 2023, and the subsequent war to defeat the culprits, by making excuses for Islamic terrorists while accusing the Jews of genocide. This might also be the right word to describe how a war in one small corner of the Middle East has morphed into a moment of cultural significance far beyond Israel’s borders. Orwell is unavailable for comment on current events. He died in January 1950 at age forty-six, but anyone who lives with his voice in their head cannot avoid wondering what he would say.

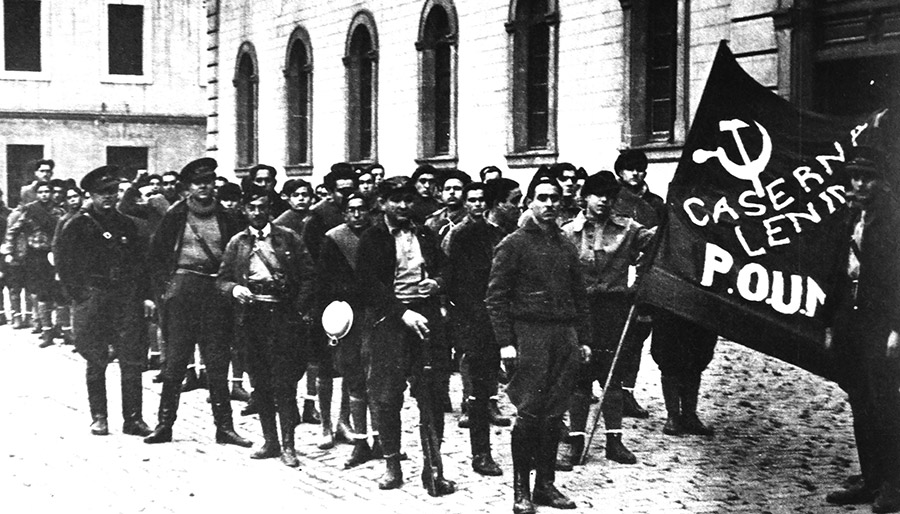

The pivotal episode of Orwell’s career was the Spanish Civil War, another local tragedy that ballooned into an international watershed, defining European politics of the 1930s and preparing the ground for the world war that would shortly follow. Orwell went to Spain at the end of 1936 meaning to write but instead joined one of the left-wing militias battling General Franco and his Nazi allies, marching with a raggedy detachment to the Aragon Front. Nearly killed by that shot in the neck, he recovered only to end up fleeing for his life—not from the Fascists but from people supposedly on his own side, Communists purging rival leftists on orders from Moscow. He arrived back in England battered and wiser, having seen through the facade of the war. It wasn’t between workers and capitalists, as he’d imagined, but between two totalitarian systems: Fascist and Stalinist. The idealism of his own comrades had been exploited and ultimately crushed by cynical Soviet power and by fellow travelers—including many of his colleagues in the liberal and leftist press, who remained committed to an ideological fantasy despite an avalanche of contradictory evidence.

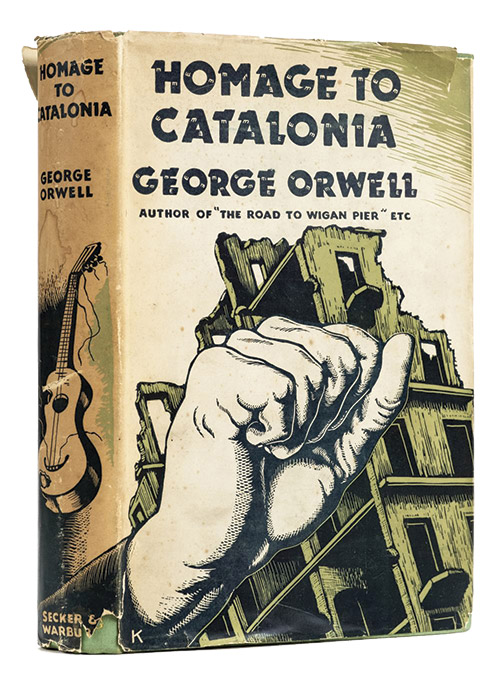

Homage to Catalonia is the famous book that came of all this, but my favorite Orwell text on the subject is the essay “Looking Back on the Spanish War,” which he composed a few years later with the benefit of perspective and with World War II already in full swing. He wrote:

Early in life I had noticed that no event is ever correctly reported in a newspaper, but in Spain, for the first time, I saw newspaper reports which did not bear any relation to the facts, not even the relationship which is implied in an ordinary lie. I saw great battles reported where there had been no fighting, and complete silence where hundreds of men had been killed. I saw troops who had fought bravely denounced as cowards and traitors, and others who had never seen a shot fired hailed as the heroes of imaginary victories, and I saw newspapers in London retailing these lies and eager intellectuals building emotional superstructures over events that had never happened. I saw, in fact, history being written not in terms of what happened but of what ought to have happened according to various “party lines.”

Many of Orwell’s comrades took his honesty about Soviet Communism as heresy, and he spent years afterward avoiding old Stalinists in pubs. An account of this time appears in a superb new biography by D. J. Taylor, Orwell: The New Life, which was published last year. Orwell’s publisher, Victor Gollancz, wouldn’t touch his book about Spain because of its anti-Soviet angle, as the biography recounts, and the New Statesman turned down his essay “Eye-Witness in Barcelona” for the same reason: it would “cause trouble.” The magazine’s editor, Kingsley Martin, explained later that though the article may indeed have been true, the editor’s decision must actually be based “on general public grounds, to the end that one side might win rather than the other side.”

All of this sounds as if it were drawn precisely from my own experience seven decades later working in the Western press in Israel, which left me with similar conclusions and ultimately led me to Orwell’s essays. It is obvious that the story in the Middle East and North Africa in our times is the rise of violent and conflicting strains of Islam and the move of these ideologies and their adherents into the West. A great deal of effort goes into obscuring this, even though the phenomenon is visible from Algeria through Syria and Yemen and Iraq to Afghanistan, and from the Twin Towers to the Bataclan theater to the Nice promenade and the Manchester Arena. For a reporter in Israel, the main local incarnations of the phenomenon are the Islamic Resistance Movement (known by the Arabic acronym Hamas) and Islamic Jihad among Palestinians and the more formidable Party of God militia (Hezbollah) in Lebanon, all allied to some extent with the Islamic Republic of Iran, all working to forge a new Islamic order, and all explicitly dedicated to erasing the unbearable pocket of Jewish sovereignty on 0.2 percent of the land of the Arab world.

This is depressing but not very complicated. However, during my time in the press, we were expected to tiptoe politely around Islam’s two billion adherents and pretend the region’s key story was a group of six million Jews oppressing a minority, the Palestinians, who only wanted a peaceful state beside Israel. Because this was mostly fictional, my colleagues and I were forced into increasingly ludicrous contortions as we “built emotional superstructures over events that had never happened,” in Orwell’s words, and buried much of what was actually happening—like Israel’s rejected peace offer of late 2008, for example, which we were instructed not to cover, or like the way Hamas followed Israel’s withdrawal from Gaza by methodically wiring the territory like a suicide bomber, building a system of tunnels under the entire civilian landscape and quite clearly condemning vast numbers to death in the holy war they promised was coming.

This all fits what Orwell understood about the way Western observers are guided chiefly by their own politics and imaginations. Atrocities in war, he wrote, “are to be believed in or disbelieved in according to political predilection, with utter non-interest in the facts and with complete unwillingness to alter one’s beliefs as soon as the political scene alters.” He would have understood the refusal by many observers in our times to believe the details of the Hamas murders, rapes, and kidnappings of October 7, while being eager to believe a few weeks later that Israel had purposely bombed a hospital—and also the unwillingness of some on my own side to admit any civilian suffering in Gaza, and the desire to dismiss anything that makes us feel bad as “Pallywood.”

Some elements of Orwell’s writing suggest he would grasp the nature of Israel’s dilemma. One example stands out in particular: a striking line from a 1938 article phrasing the horrific dilemma of modern industrial war, which I read for the first time in Taylor’s biography. “The only apparent alternatives,” Orwell wrote, “are to smash dwelling houses to powder, blow out human entrails and burn holes in children with lumps of thermite, or to be enslaved by people who are more willing to do these things than you are yourself.” He hated wars, nationalism, and the British Empire, whose rapaciousness and racism he’d seen up close while a young man serving as a colonial policeman in Burma. But when World War II came, he tried to join the British Army, was rejected because of poor health, and ended up an enthusiastic recruit to the Home Guard. A responsible person will have to choose among poor options or different kinds of evil.

This might lead us to think Orwell would sympathize with Israel’s problem, or at least understand it. It’s hard to imagine Orwell seeing marches through London in support of Hamas as somehow in harmony with the left. But other elements of his work offer a Jewish admirer in 2024 fewer grounds for optimism. The new biography details an editorial meeting at the left-wing journal Tribune in 1943, for example, in which the editor made a speech embracing Zionism—hard to imagine now but quite logical at the time, when Zionism was dominated by the workers’ movement and with the gas chambers working at maximum capacity. Zionists, Orwell replied to the surprise of his colleagues, were “only a bunch of Wardour Street Jews who have a controlling interest over the British press.”

If his colleagues were surprised, they might not have read Down and Out in Paris and London, his first book, and its description of a London coffee shop where, “in the corner by himself a Jew, muzzle down in the plate, was guiltily wolfing bacon.” His diaries include several similarly ugly descriptions, including one of a “little Liverpool Jew” with a face that “recalled some low-down carrion-eating bird.” We may charitably observe that such descriptions were common across generations of British literature and that these appeared on Orwell’s pages before the Nazis made clear where such loathing would lead. But surely a man of his ideals and sensitivity should have known better.

By war’s end, with the horrors of Nazism evident to all, Orwell was capable of writing a thoughtful essay for the Contemporary Jewish Record grappling with antisemitism. My favorite part is a roundup of things he’s heard ordinary Londoners say about Jews. “Tobacconist (woman): ‘No, I’ve got no matches for you. I should try the lady down the street. She’s always got matches. One of the Chosen Race, you see.’” He recalls rumors that inflamed London at one point during the Blitz, when a fatal stampede at an Underground station was blamed on the Jews, and concludes, “To attempt to counter them with facts and statistics is useless, and may sometimes be worse than useless”—good advice for the well-meaning Jews who today pour money into quixotic campaigns against antisemitism. “Clearly, if people will believe this kind of thing,” he writes, “one will not get much further by arguing with them. The only useful approach is to discover why they can swallow absurdities on one particular subject while remaining sane on others.” But he remarks in the same essay that the antisemites occasionally do have a point, like the critique of Jews as petty exploiters in small-time commerce or the idea that “the Jew is a person who spreads disaffection and weakens national morale,” which he deems true of the “intellectuals” of the 1930s. We learn from the new biography that Orwell’s friend Malcolm Muggeridge believed him to be “at heart strongly anti-Semitic.” This thought crossed Muggeridge’s mind during Orwell’s funeral at an Anglican church in Oxfordshire, where he “reckoned the congregation was largely Jewish.” Orwell’s first publishers were Jews and so, if I may, were some of his best friends, notably Tosco Fyvel, later editor of the Jewish Chronicle and author of a memoir about Orwell, also a committed Zionist whose mother was a secretary to Chaim Weizmann.

Orwell’s excellent question, “why they can swallow absurdities on one particular subject while remaining sane on others,” could be posed to him, just as it could be posed today to someone like Andrew Sullivan, another British-born cultural observer who is skeptical of many media narratives but seems to believe the ones about Israel. “How Many Children is Israel Willing to Kill?” was the headline of a recent article by Sullivan, one whose emotional superstructure—drawn from the internet, hard-left NGO propaganda, and the dark recesses of the Christian imagination—was about what you’d expect.

Overt narratives of Jewish evil are back in the mainstream, as in the recent London Review of Books cover story declaring that Israel’s war in Gaza was a deliberate slaughter of innocents that exploited the Holocaust while effectively transforming Jews into the new Nazis. The author, an Indian intellectual named Pankaj Mishra, obviously knew little of real Israelis or Palestinians and was writing from abroad and from his own imagination. Yet he was applauded for his bravery by figures like the British historian William Dalrymple, whose manic Twitter activity during this war has included comparing Israelis to feudal overlords and Genghis Khan. Orwell’s name, which is invoked in Mishra’s essay, hovers over much of this discussion.

So what would Orwell write? The question is akin to the hope of a forlorn Lubavitcher flipping open the dead Rebbe’s Holy Letters—the great man, one suspects, will think what we want him to, and would rightly resent the enterprise. It’s better to ask how we may use what’s great in Orwell’s spirit to understand and explain our own world.If we seek lessons in his life and work, these are apparent: Majority opinion is overwhelming but often wrong. Wars look different close up than they do from afar. Time in uniform will make you wiser than time in school. Writing that lasts is more likely to appear in small journals than in the mainstream press. Those who ride the ideological currents may rise but will then sink, and in posterity only the honest observer has a chance of staying afloat.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Fire Now

"As horrific as the Holocaust was, it is firmly in the past. . . . Though I remain horrified by what happened, it is history. Contemporary antisemitism is not. It is about the present. It is what many people are doing, saying, and facing now," writes Deborah Lipstadt in her latest book.

The Ukrainian Question

"If I had to choose between Hitler and Stalin, Adam Michnik once said, I pick Marlene Dietrich." Vladimir Putin's propaganda notwithstanding, this is not the choice facing Ukrainian Jews.

Lost from the Start: Kafka on Spinoza Street

Jerusalem-based writer Benjamin Balint has crafted a wise and eloquent study of Kafka around the eight-year battle in Israeli courts over Max Brod’s literary estate.

Israel’s Sea Change

The first Zionist ship was a refurbished English vessel with 20 years of rough service behind her, including the wartime evacuation of Singapore in 1941.

Zachary Narrett

I believe Orwell the master journalist and essayist would appreciate this article for its eloquence, wisdom, and truth.

Daniel Saunders

Orwell has been informing my view of Israel, the West and Islamism for twenty years, despite his antisemitism and anti-Zionism.

A couple of passages in my head in recent months: the bit from Inside the Whale where he attacks left-wing intellectuals who speak of "necessary murders" as people who are never around when the trigger is pulled and that much of left-wing rhetoric is "playing with fire by people who don't even know that fire is hot." Queers for Palestine, he sees you.

The other is a line (I don't remember which essay it's from -- maybe The Lion and the Unicorn) about the difficulty free democratic nations have fighting "nations who breed like rabbits and whose chief industry is war" (quoting from memory, but it's about right) which is not a very politically correct or woke thing to say nowadays, but which happens to still be very true and very relevant.