Life and Text

Life and tradition are in constant interaction,” writes Michael Fishbane in Fragile Finitude. It is Fishbane’s second work of personal theological reflection after a long and distinguished career as both a historian of biblical interpretation and an original interpreter of Jewish texts. In these books Fishbane describes how the words of tradition call us to attention and, in acts of exegesis, form the ground from which spiritual life blossoms.

Is Jewish theology really possible in our day? Fishbane insists that it is and that such work is a spiritual, cultural, and personal necessity. He argues that our interpretations of canonical Jewish texts are necessarily shaped by contemporary experience. But his thesis is stronger yet: interpretation is the lifeblood of religious consciousness, and it is simultaneously the key to our being in the world. We must, Fishbane writes, “cultivate a mind devoted to God’s all-creative vitality in worldly reality,” and the Jewish way to do so is through interpretation.

Fishbane begins with a striking reading of Job. In response to his bold questioning of God, Job receives not platitudes but a voice from a whirlwind challenging him to appreciate each and every created being. This revelation decenters Job, giving him new eyes. For Fishbane, Job’s private transformation serves as a template for moments of awakening to the world, a template that is open to modern seekers as well. We live in a kind of Jobian moment of inexplicable suffering, rupture, and breakdown, he suggests, and something new must emerge from the “collapse of older ideologies.” The heart of Fragile Finitude is a yearning to hear the kol, a voice of God that is audible yet lacking in the specific forms of language. This sacred voice is unending, claims Fishbane, and it continues to speak in infinite ways by calling us to attention through the unfolding of all things. “The divine voice is not hearable as such within the natural phenomena, but leaves the trace of an ineffable mystery, a spiritual echo of the awesome experience.”

Our responses to this voice are shaped by tradition, which gives us language. Scripture is itself a textual response to ineffable revelation, and hence, we ought to “study these canonical depictions of theological living and to appropriate them in accordance with scriptural values, tradition, and our modern sensibilities.” In this way, we add new personal layers to tradition by giving language and form to moments of inspiration and awakening.

From the Zohar on, medieval Jewish mystics spoke of four levels of biblical meaning: the peshat, or plain-sense contextual meaning of a scriptural passage; derash, the exegetical meaning as derived in rabbinic tradition; remez, the allegorical meaning; and sod, the esoteric, or mystical, meaning. The famous acronym for this is PaRDeS (literally, orchard). Fishbane used this traditional template in his marvelous 2015 JPS Bible Commentary: Song of Songs. Thus, on the famous verse “Let him give me of the kisses (yishaqeini) of his mouth, For your love is more delightful than wine” (Song 1:2), Fishbane comments:

Peshat . . . The verb yishaqeini expresses volition or desire. It articulates the speaker’s intense longing for a kiss. . . . The reader is drawn into this maiden’s intimate subjectivity and becomes a partner to the Song’s emotions. Every expression of intimacy is seen or heard. The reader is thus an all-present audience, a counterpart to the all-seeing and omniscient author.

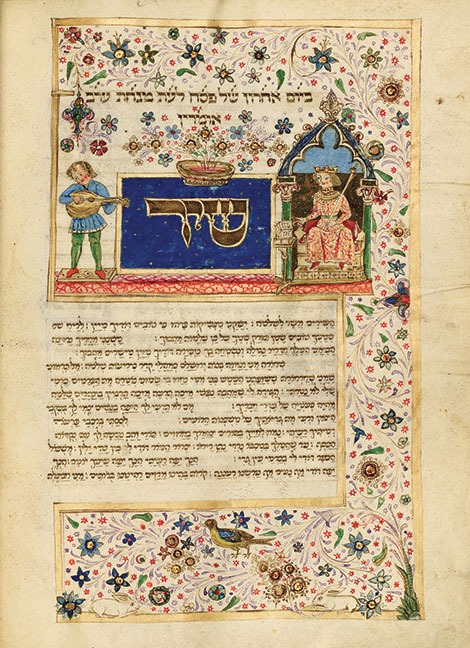

Illumination for the opening verse of Song of Songs, the Rothschild Mahzor, Florence, Italy, 1492. (The Jewish Theological Seminary of America.)

Derash . . . At the center of covenant love stands Mount Sinai, the classic site of a revelation whose words are like kisses—sealing a bond for all generations. . . . The cry yishaqeini (“Let Him kiss me”) is the voice of each and every worshiper (for the task is individual and collective) who eagerly wants to receive the kisses (neshiqot) of Torah. . . . This spiritual process renews Sinai at every moment.

Remez . . . Spiritual realization is ever partial and fragmentary. The honest seeker knows that the goal is to make contact with some modality “of” (or “from”) the great divine mystery—with something that remains hidden and other (“His”), even as one dares to imagine the connection in terms of knowable and human (“mouth”). . . . The kiss represents the desired infusion of divine reality into the human self—the yearning for spiritual transformation. It is a moment of meeting that silences speech.

Sod . . . The spiritual quest begins with great longing, marked by absence and otherness (as marked by the third-person Hebrew pronoun). It wishes for contact with Divinity, symbolized by a kiss. Spiritually understood, the kiss is the co-infusion of breath or spirit between one being and another.

Fragile Finitude extends the fourfold model of interpretation, offering it as a method for hearing the divine voice and for making sense not only of canonical texts but of personal experience. This possibility reflects Fishbane’s understanding that creation and revelation are parallel self-disclosures of the divine, both of which call for human interpretation.

For Fishbane, a theology of peshat is the acknowledgment that, as finite and embodied beings within the physical world, we are surrounded by a multitude of real-world phenomena that command our attention and invite interpretation.

But we are also social beings, and that is the realm of derash, which the classical rabbis used to create community. Fishbane intimates that even the Torah itself is a kind of derash,a textual witness to an ineffable—and unending—event. Modern readers and exegetes such as Fishbane are guided by the classical rabbis’ thinking and their reverence for scripture, approaching them as a model for commitment to the canon while bringing forth new ideas and applying language to a God that remains beyond words.

The search for “individual expression”takes place within the domain of remez, also the site of allegorical, metaphorical, and philosophical interpretations. The texts of our tradition shape this interior journey as do “the social claims or existence of other creatures.” Of course, some fuzziness plagues these categories, and remez—standing as it does between the thickness of derash and the interior mysteries of sod—is somewhat undeveloped. Such ambiguity might be expected, however, as Fishbane reminds us we are not meant to commit ourselves exclusively to any one level.

The fourth level, sod, is that of mysticism. Like Job, we confront the whirlwind of mysterious complexity that surrounds a unity that cannot be spoken: “At the border of speech and silence we sense the great mystery of creation in the depths of God-given being.” The traditional sources from Kabbalah and Hasidism guide us in uncovering the mysteries found beneath the textual and ritual bedrock of the tradition, but this is more than an intellectual enterprise; modern seekers must open their own hearts to creative wonder.

“Taken together,” writes Fishbane, “these four levels of interpretation helped formulate a ladder of religious or spiritual development, with each successive level absorbing the truths of its predecessors into a dynamic synergy.” Despite the inevitable metaphor of the ladder, Fishbane’s PaRDeS is perhaps more of a spectrum than a hierarchy. In this, his approach to spiritual reflection mirrors the many simultaneous layers of human consciousness as well as the multivocal biblical text.

Although Fragile Finitude draws upon both rabbinic and Western philosophical traditions, Fishbane’s readings are frequently shaped by classical Kabbalah’s conception of an all-expansive Torah that predated creation and by Hasidic thinkers who attempt to awaken their readers to derekh ha-avodah—the spiritual work in this world that emerges from encountering a canonical text. In Fishbane’s terms, the experience of sod returns us to the ethical demands of peshat as “we realize that we cannot abandon our concrete lives; and must engage our spiritual quest from within the particulars of our experience, language and community.”

The mitzvot are prompts to attention, acts of recentering and awakening that also link us to the community. But, Fishbane insists, commitment to normative Jewish practice cannot be allowed to squeeze the spirit of vitality from the mitzvot. “Norms may give us the general structure,” argues Fishbane, “but modifications are required amid the complexities of life.” God does not command in a literal sense, yet the mitzvot ought to be understood as reflective responses to the commanding divine summons. Astute readers will hear echoes of the famous “Builders” debate between Franz Rosenzweig and Martin Buber, with Fishbane suggesting that formal laws can once more be transformed into commandments when they are approached as a way of life rather than abstract law.

Fragile Finitude is a book of personal theology, written from the heart and much concerned with questions of private devotion and interiority. Yet Fishbane, whose own spiritual life was shaped by participation in Somerville’s Havurat Shalom while in graduate school at Brandeis in the late 1960s, is personally committed to the necessity of a living community and traditional observance. He believes that creative theology must strive “to build (or reinforce) a common ethical or spiritual vision.”

Fragile Finitude is a very important contribution to the practice and theory of Jewish spirituality. In 1975, Fishbane wrote:

PaRDeS was, itself, a programme or strategy of reading and interpretation in the deepest sense. It allowed a reader to distinguish different levels of meaning in the Bible, but without having to relinquish any one of them. We moderns are faced no less with the need to conceptualize the multiple dynamics of the hermeneutical task.

Almosta half-century later, Fishbane has made good on the promise of using PaRDeS as a “strategy of reading and interpretation in the deepest sense” on the challenges of modern Judaism. He has provided a conceptual structure for contemporary Jewish theology and practice. Fragile Finitude is a demanding work that asks a great deal from the reader, but it is also me’irat eynayim—illuminating and eye opening—awakening its readers to the Jewish—and human—task of living in the presence of the sacred.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

I Have Come to My Garden

Without the Torah, says Rabbi Akiva, we would still be able to discover all its truths by delving deeply into the words of the Song of Songs.

Hasidic Renewal on the Brink of Destruction

Kalonymus Kalman Shapira, a Hasidic communal leader, and Hillel Zeitlin, a writer who sought to bring Yiddish religious books to a new audience, met on the page, and almost certainly in the Warsaw Ghetto.

Our Rabbis J, E, P, and D

At the heart of Benjamin D. Sommer’s project is a contrast between the stenographic theory of revelation and what he calls the “participatory” theory, which “puts a premium on human agency and gives witness to the grandeur of a God who accomplishes a providential task through the free will of human subjects under God’s authority.”

Hardware, Software—or Love?

Maimonides’s Abraham was a natural philosopher who discovered God through reason, but the biblical Abraham did nothing at all to earn God’s election.

gershon hepner

THE BIBLICAL LADDER AND ITS SPECTRUM

Biblical interpretation may be thought of as a ladder

involving an ascent for the allegedly plain meaning of the text, peshat, frequently as inaccurate as can be any dictation,

followed by remez, hints to meanings that are normally a little madder,

and moving with far more deliberation to derash, a meaning of the text that is a parafictional, creative derivation,

At the summit of the ladder you may reach

A meaning that is dangerous to teach,

appropriately called a secret, sod

the Hebrew word for it, extremely odd,

like people who are on the spectrum, as atypical

although their meanings sound terrific, all

very hard to understand, in contrast to

ones far more typical, appreciated by just few

devoted followers, as is very sadly true

of peoples who hold spectral points of view,

which while to understand them is extremely hard, are

sometimes more comprehensible than verses of a baffled bard are.