Scribes without a Torah

The Treason of the Intellectuals is one of those books that is famous even though almost no one actually reads it. Julien Benda’s title—either in English translation or the original French, Le trahison des clercs—has been a favorite shorthand in intellectual debates since it was published in 1927, invoked whenever one intellectual wants to accuse another of moral failure. In recent years, the liberal historian Anne Applebaum applied the phrase to conservative thinkers who supported Donald Trump; the far-left journalist Chris Hedges used it to denounce PEN, a writer’s group that defends press freedom, for failing to support Julian Assange and WikiLeaks; and the late rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks used it to denounce students and faculty who silence controversial speakers on college campuses.

One reason the phrase has endured is its flattering suggestion that intellectuals have greater moral obligations than humanity at large. Every one of us is charged not to murder or bear false witness, but people who reason in public are a special caste and should be held to a higher standard—much as, in Jewish law, priests are liable to certain kinds of impurities that ordinary people don’t have to worry about.

The problem is that, unlike priests, intellectuals have no Leviticus to tell them what’s taboo. Treason is in the eye of the beholder, and in practice it’s often hard to distinguish from plain old disagreement. The appearance of a new English translation of The Treason of the Intellectuals shows that this slipperiness has been a problem from the beginning, ever since “intellectual” emerged as a noun during the Dreyfus affair in the 1890s.

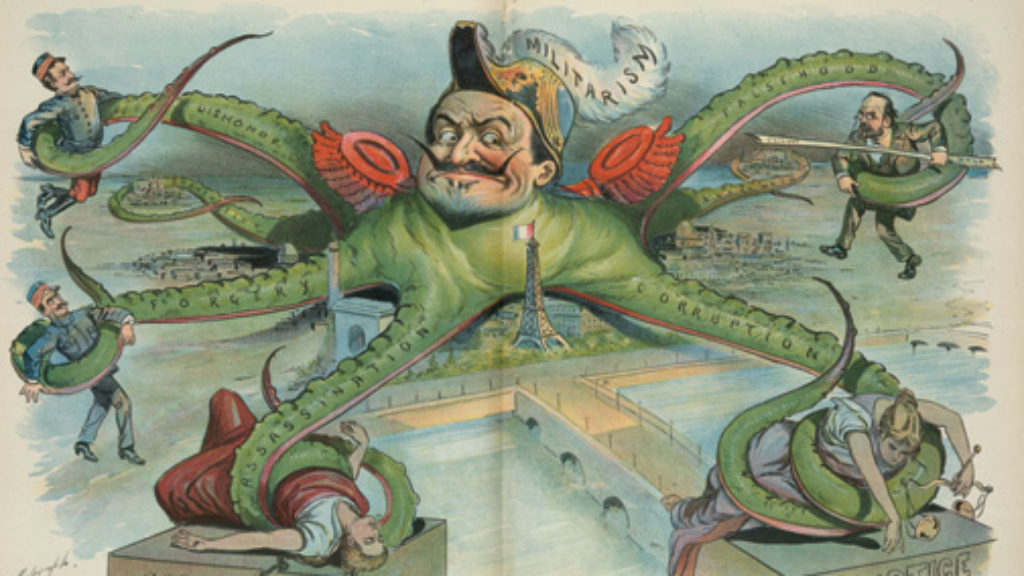

The affair began as a debate over the guilt or innocence of Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer in the French army convicted in 1894 of passing military secrets to Germany. But it quickly turned into a fierce culture war between secular progressives, who supported France’s Third Republic, and conservative nationalists and Catholics, who detested it. When evidence emerged that Dreyfus was innocent and had been railroaded by an antisemitic officer corps, the affair only became more bitter, as anti-Dreyfusards argued that the honor of France and its military shouldn’t be besmirched for the sake of a Jew. There were things at stake more important than the truth.

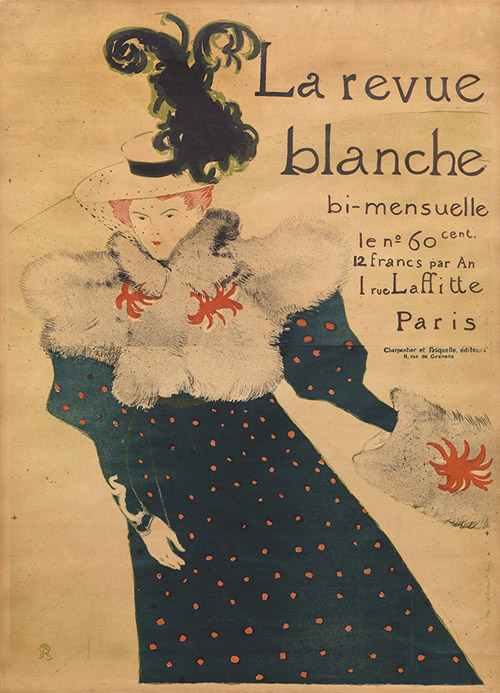

Some of the leading figures in twentieth-century France entered public life during the Dreyfus affair, including the novelist Marcel Proust, who was Jewish on his mother’s side, and the Socialist politician Léon Blum, who became France’s first Jewish prime minister in the 1930s. Both were associated with the pro-Dreyfus La Revue Blanche, a literary magazine launched in 1889 by the Natanson brothers, whose father, a Jewish banker, immigrated to France from Warsaw.

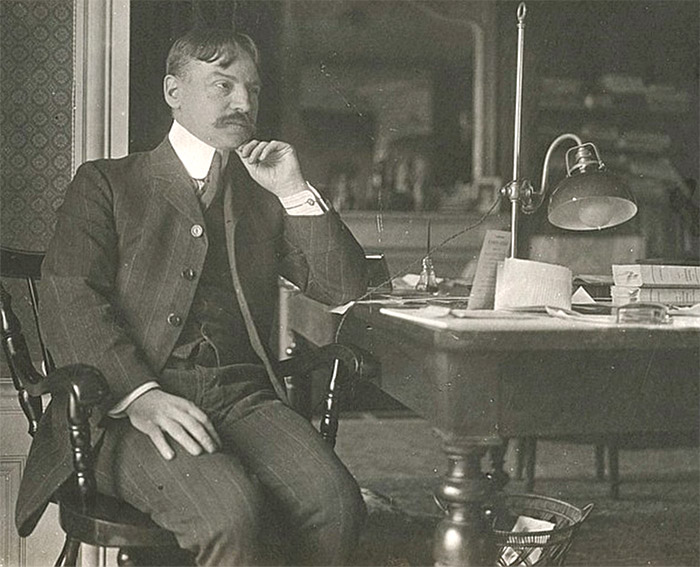

Julien Benda belonged to the same milieu. Born to a secular Jewish family in Paris in 1867, he made his debut as a writer in La Revue Blanche in 1891 and went on to publish many fiction and nonfiction books. Though his books are seldom read today, when Le trahison des clercs appeared, he was one of the country’s most respected writers. In 1912 he was a leading contender for the Prix Goncourt but lost due to the opposition of the jury chairman Léon Daudet, who was a leading anti-Dreyfusard and antisemite. The episode, which caused a scandal at the time, showed that the divisions opened up by the affair were still central to French intellectual life long after Dreyfus himself was exonerated and pardoned.

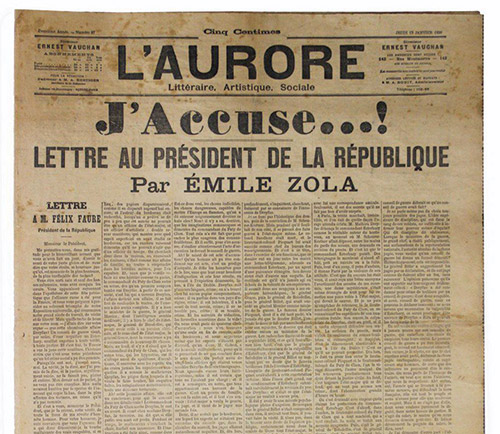

For Dreyfusards like Benda, the hero of the affair—the archetypal modern intellectual—was the novelist Émile Zola. In 1898, Zola published “J’Accuse,” an open letter to the president of France laying out the case for Dreyfus’s innocence. He accused several high-ranking officers by name of participating in a cover-up, noting that in doing so, he was exposing himself to prosecution for libel. Zola was duly tried and convicted of defamation, avoiding imprisonment only by fleeing the country for England.

The term “intellectual” entered the debate when L’Aurore, the newspaper where Zola’s letter appeared, published a statement of support written by its editor, Georges Clemenceau, who would later lead France to victory as prime minister during World War I. It was signed by many prominent cultural figures, described by Clemenceau as “all these intellectuals, from every point on the horizon, who join together under one idea.”

The right-wing writer and politician Maurice Barrès quickly replied with an essay titled “Protest of the Intellectuals,” attacking those who had taken up Dreyfus’s case. In an occupational sense, Barrès was an intellectual too. A prolific man of letters who emerged as a novelist in the 1880s, he used fiction and essays to express the political ideas he fought for as a longtime member of the Chamber of Deputies. But he insisted that he wasn’t an intellectual in Clemenceau’s sense. “What is an intellectual? An individual who persuades himself that society should be founded on logic, not knowing that in fact it rests on prior necessities that can be foreign to individual reason,” Barrès explained.

This was intended as a criticism, but it’s not far from what Zola said

about his own motives in “J’Accuse.” He had spoken out and put himself at risk

precisely because he believed society should be founded on principles: “The

action I am taking is no more than a radical measure to hasten the explosion of

truth and justice,” he wrote. For Zola, there was no necessity prior to truth

and justice; no considerations of national interest or honor could justify

sending an innocent man to Devil’s Island. “I have but one passion, the search

for light, in the name of humanity which has suffered so much and is

entitled to happiness,” he declares in the peroration.

For Benda, this single-minded devotion to principle was the intellectuals’ special contribution to the welfare of humanity. They are the latest incarnation of a human type that has played a similar role throughout history, which Benda calls the clerc. The French word is cognate with the medieval English “clerk,” meaning a member of the clergy, but a clerk wasn’t necessarily a priest, just a literate man.

Though David Broder’s new translation keeps the traditional English title “The Treason of the Intellectuals,” in the text he renders clerc as “scribe,” an inspired choice that captures the association of wisdom, writing, and the sacred, evoking the Biblical soferim Ezra and Baruch. For Benda, scribes were “an uninterrupted series of philosophers, churchmen, men of letters, artists, and scholars” stretching back to antiquity, though most of his examples came from Western Europe after the Renaissance, including Leonardo da Vinci, Goethe, Erasmus, Kant, Galileo, and Montesquieu.

These figures have little in common in terms of what they actually did and thought, but for Benda, they were all scribes because of their “explicit opposition to the realism of the crowds.” By “realism,” he meant the pursuit of the worldly advantages that most people consider the only real goods in life, such as money, status, and power. Scribes, by contrast, “preached the adoption of an abstract principle superior to and directly opposed to these passions, in the name of humanity or justice”—the very principles Zola invoked in “J’Accuse.” The sine qua non for a scribe is to seek truth instead of gain.

Looking at history, one might conclude that the purity of the scribes hasn’t done much to improve the moral character of the nonscribes. Benda acknowledged as much, and his claim for the value of scribes was pointedly minimal:

It is thanks to these scribes . . . that humanity did evil for two thousand years but nonetheless paid tribute to the good. This contradiction was an honour to the human race, opening up the crack whereby civilisation could occasionally slip through.

Writing in 1927, Benda saw that crack closing, and he held the scribes responsible. “Our century,” he observed in the book’s most famous sentence, “will properly be called the century of the intellectual organisation of political hatred.” In the past, kings made war on one another, but their subjects remained largely indifferent. Now fascism and communism had made political hatred universal and self-conscious; people believed it was virtuous to hate members of a different nation, race, or class. Philosophers openly claimed that there was no universal truth but a French truth and a German truth, a bourgeois truth and a working-class truth.

This was a new kind of hatred based on ideas, and it could not have happened, Benda believed, without the connivance of the traditional custodians of ideas. The scribes had become realists, exalting power and gain like everyone else. Benda compared them to Callicles, Socrates’s interlocutor in the “Gorgias,” who argues that might makes right and that people only praise justice because they’re too cowardly to simply take what they want. The difference is that the modern scribes’ desires aren’t for themselves as individuals but for the collective to which they belong:

After preaching for twenty centuries that the state should be just, the scribes now proclaim that the state should be strong and pay no attention to justice (one need only recall the most important French scholars’ attitude during the Dreyfus affair).

Indeed, while Germany and Italy could have offered plenty of examples of intellectual treason, Benda was mainly interested in the failures of French scribes. His examples included Georges Sorel, who urged the working class to revolt in Reflections on Violence, and Charles Maurras, the founder of the protofascist group Action Française, who would later be convicted of collaborating with the Germans during World War II.

But the name that appears most often in the book is Maurice Barrès. Like Zola, Barrès was radicalized by the Dreyfus case, but in the opposite direction. Instead of truth and justice, he glorified la terre et les morts, the earth and the dead, which he saw as the basis of the mystic unity of the French nation. It was on these grounds that Barrès became a fierce antisemite, seeing Dreyfus as a representative of a conspiracy of aliens whose earth and dead lay elsewhere. “That Dreyfus is capable of treason I deduce from his race,” Barrès wrote. If he shouldn’t be called a traitor, it’s only because “Dreyfus doesn’t belong to our nation, so how could he betray it?”

Historians like Michael Curtis and Zeev Sternhell have followed Benda’s lead in seeing Barrès, Maurras, and Sorel as key intellectual precursors of fascism. In attacking the Enlightenment and democracy while exalting violence, nationalism, and unreason, they created a blueprint for the fascist ideology that would find mass support after World War I. The major innovation of Nazism was to add biological racism to the mix: Where the French thinkers called for war between nations and civilizations, Hitler envisioned a Darwinian fight for the survival of the fittest race. But he agreed with Barrès and Maurras about the identity of the chief antagonist, which was of course the Jews.

In The Treason of the Intellectuals, however, antisemitism is the dog that doesn’t bark. Benda acknowledges early in the book that “the movement against the Jews” is one of the chief drivers of the political hatred he deplored; later he observes that “the scorn which the likes of Barrès have displayed toward the Jews . . . has brought real damage to the objects of their contempt.” Yet that is the sum total of his discussion of the subject. It would be easy to read Treason without realizing that it is a book by a Jewish writer attacking notorious Jew-haters and that the Jewish question had been bound up with the very issues Benda was writing about since the Dreyfus affair.

During World War II, when the triumph of unreason and of antisemitism were at their peak, Hannah Arendt wrote:

One truth that is unfamiliar to the Jewish people, though they are beginning to learn it, is that you can only defend yourself as the person you are attacked as. A person attacked as a Jew cannot defend himself as an Englishman or Frenchman. The world would only conclude that he is simply not defending himself.

The Treason of the Intellectuals is a perfect case in point. Not only did Benda not write as a Jew, he seemed to write as a Christian: “We will have to look among those who have left the Church if we want to hear Christian ministers who will profess their Master’s true teaching,” he wrote. Indeed, for Benda, the true clerc is an explicitly Christlike figure: “These scribes all say, in one way or another: ‘My kingdom is not of this earth.’”

And it is this Christianization of the intellectual that led Benda’s argument astray. The central idea in The Treason of the Intellectuals is that a clerc should scorn realism because it is contrary to his special vocation. The “absence of practical value is the very thing that gives his teaching its grandeur,” Benda writes. “The proper morality for the prosperity of kingdoms (which are, indeed, worldly) is the morality of a Caesar and not his own erudite one.” Benda’s clerc renders this world unto Caesar and unto God what is God’s.

This distinction is only compelling, however, if there is a God to render to. A religious vocation depends on religious faith. Benda, like Zola and most modern intellectuals, was aggressively secular, and he could offer no better justification for clerkish aloofness than guild loyalty or esprit de corps. The ultimate punishment for the intellectual traitor, he writes, is to be kicked out of the club: “The just man . . . will accuse him of cunning and expel him from the ranks of the scribes.” Ever since, intellectuals have wielded the charge of treason against one another like a blackball.

But the contempt of Benda and the Dreyfusards didn’t make reactionary intellectuals like Barrès and Maurras doubt their bona fides. They had their own definition of what it meant to pursue truth and goodness, and plenty of people agreed with them, including many inside the literary establishment: both were elected to the Académie française. Six years after Benda wrote, Martin Heidegger emerged as an enthusiastic Nazi, at least for a while, and any definition of intellectual or scribe or clerc that excludes Heidegger is self-evidently inadequate.

Indeed, as Mark Lilla writes in his probing introduction to this new edition, Benda himself ended up committing exactly the kind of treason he denounced. In the 1930s, he joined many erstwhile liberals in becoming a fellow traveler, defending the Soviet Union despite its blatant crimes against “truth and justice.” The scribe who once believed it was unacceptable for France to imprison one innocent man now defended the right of the Communist Party to execute thousands. Lilla quotes a passage Benda wrote in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War:

I say that the scribe must now take sides. He must choose the side which, if it threatens liberty, at least threatens it in order to give bread to all men, and not for the benefit of wealthy exploiters. He will choose the side which, if it must kill, will kill the oppressors and not the oppressed.

After the German occupation of France in World War II, which Benda survived in hiding, he continued to be a vocal fellow traveler until his death in 1956.

Benda’s evolution shows why the charge of treason is useless when it comes to keeping intellectuals on the straight path. It isn’t an argument, it’s a meta-argument: an argument about what arguments are allowed to be made. By definition, however, thinkers who go beyond the boundaries of legitimate opinion have stopped caring about being called illegitimate, just as politicians who violate laws and norms wouldn’t stop even if all the editorial boards in the world condemned them. Intellectual traitors believe they are answerable to a more important authority than scribedom, whether it is the nation or the international working class.

To really refute advocates of violence and unreason—in the 1920s or the 2020s—requires coming to grips with primary problems. Does national belonging depend on religious or ethnic identity? Is reason shallow and violence redemptive? Can it ever be right to send an innocent person to prison? These are not unlike the difficult, substantive questions that Socrates tried to answer, but he never thought that he could best Callicles simply by telling him that he had betrayed his calling.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Saladin, a Knight, and a Jew Walk Onto a Stage

Outside of Germany, Nathan the Wise is one of those works more often read than performed, and more often read about than actually read.

An Affair as We Don’t Know It

Harris retells the “Dreyfus Affair” from Lieutenant-Colonel Marie-Georges Picquart’s point of view, dramatically reconstructing how he zeroed in on the true culprit.

The Jewish Critic and the Devil’s Point of View

We have never met this Mendele before, but he expects us to trust him, appreciate his wit, catch his references, and share his attitudes. In a few deft lines, the author created a figure so democratic you don’t have to look up to him, so familiar you don’t have to fear him, and so appealing you won’t realize you’re being flogged.

The Rogochover Speaks His Mind

After he visited the odd talmudic genius, Bialik said that “two Einsteins can be carved out of one Rogochover.”

gershon hepner

LACKING A LEVITICUS

To know what is taboo our intellectuals don’t have a Leviticus

informing them what sort of culture they should, since it is unkosher conduct, cancel,

so they don’t know what of sex it’s right for them to, in their city, cuss,

and whether it is a transgression for a Gretel to transform into a Hansel.

Janet Rice

Great article. Great points.

Re Anne Applebaum's purported liberalism, though -- and I think the term is being used in the conventional American way, as the opposite of "conservative" -- she has called herself center-right in the pages of The Atlantic.