As the Story Goes: Hanukkah Spears, Cheese, and Goblins

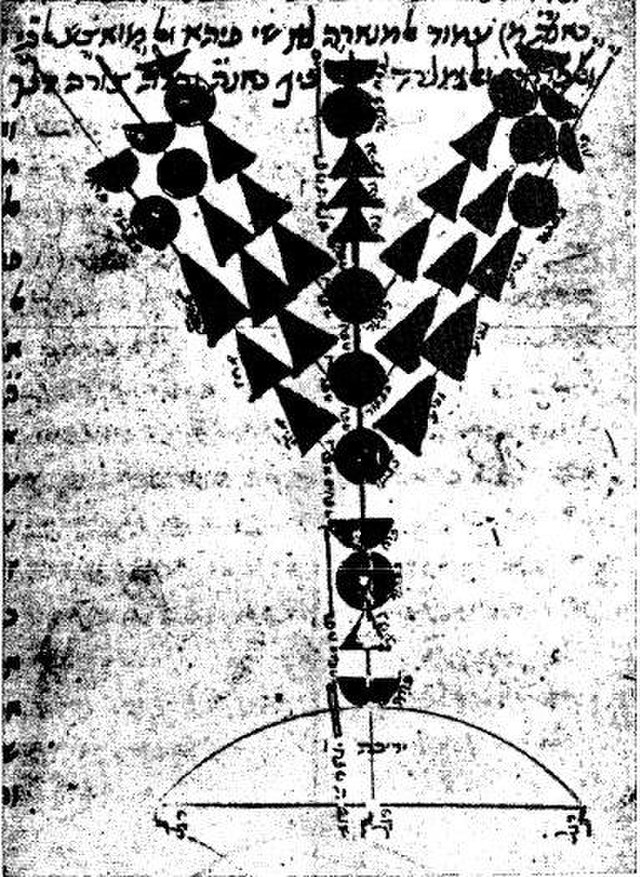

Last week on Twitter, an entertaining battle was raging: not the annual sour cream versus applesauce on latkes feud. It was tweet versus tweet, all citing sources and showing figures, arguing whether the original Hanukkah menorah had curved branches or if the branches were straight, jutting out from a common bottom spot. Proponents of that style—which today includes Chabad, and, historically, may or may not have included the great Torah commentators Rashi and Rambam (depending on who is interpreting their work)—argue that uncurved branches are the straight reading of the text. We won’t settle that debate today, but it puts in context a related midrash that claims the original Hanukkah menorah wasn’t from the Temple—whether curved or straight, the gold Temple menorah had been looted and lost. Instead, the Hanukkah menorah was crafted from the iron spears of defeated Greeks that the triumphant Maccabees fancied up, jammed into the Temple floor, and wrapped with tin. We relit the holy light of the Temple with weapons of our defeated enemy.

That’s quite a legend and is, surprisingly, one of the few. Unlike other Jewish holidays, Hanukkah is literarily sparse. Passover, by comparison, is absolutely swamped with stories, side adventures, wild midrash, and engaging commentary. The Exodus, to the rabbinic imagination, is a never-ending moment filled with burning bushes and pillars of fire, giant frogs and vegetable apes, coffins hidden in the Nile, guardian angel battles, Moses’s staff, Miriam’s well, and the Ark of the Covenant

The rabbis just don’t seem to like Hannukah very much. Our primary sources for the events, 1 and 2 Maccabees (or Sefer ha-Makabim) were never accepted as part of the Tanakh. The books belong to the Apocrypha, and observant Jews were long cautioned to avoid them. Maybe the martial victory never sat well with the rabbis: the Maccabees fought and defeated the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire, but apparently without God’s aid. In stark contrast, we read from the book of Zechariah as the haftarah for the week of Hanukkah. Zechariah’s “Not by might, not by power, but by My spirit—said the Lord of hosts” is the opposite of Hasmonean self-reliance. And of course, maybe the rabbis just never accepted the Maccabees’ legitimacy. The Hasmonean dynasty they established wasn’t of the Davidic line and didn’t sustain their zealous anti-Hellenic fervor very long. Big disappointment, politically and religiously speaking. So instead, the rabbis wrapped the victory in a midrash about the oil lasting nights and called it done. (Although don’t forget the spears.)

All these gaps, elisions, and tensions are what make the other great story associated with Hanukkah so striking:

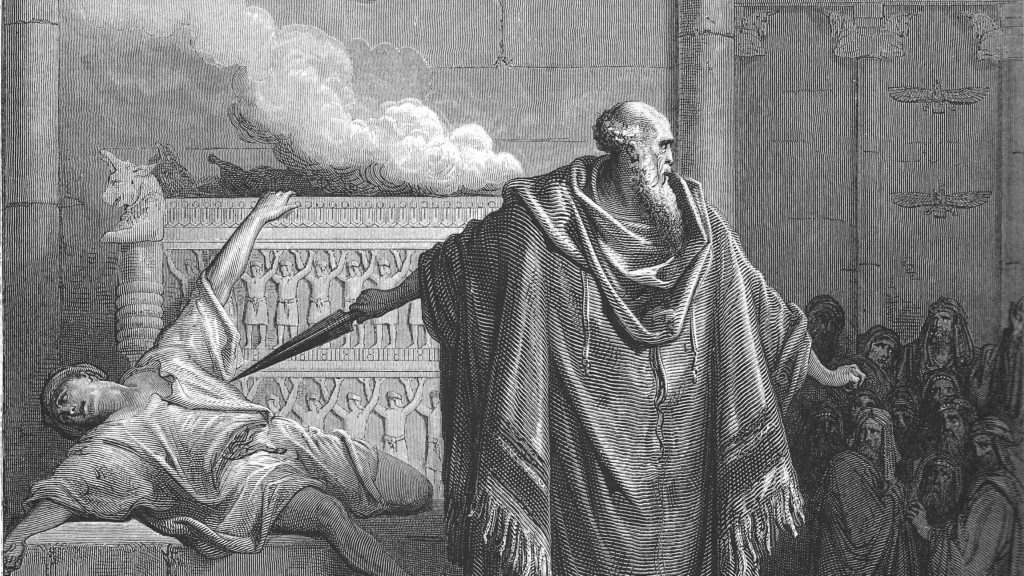

Her name was Judith, as the story goes, and she was the daughter of Yochanan, the high priest. She was extremely beautiful, and the Greek king wanted her to lay with him. She fed him a dish of cheese to make him thirsty, so that he would drink a great deal and became drunk and recline and fall asleep. And it happened just that way, and once he was asleep, she took his sword and cut off his head. She brought his head to Jerusalem, and when the armies saw that their leader had been killed, they fled. For this reason, we have the custom of eating a cheese dish on Hanukkah.

It’s not clear why Judith became so beloved to medieval Jews, but the apocryphal protagonist of the book of Judith was Hanukkah’s answer to Purim’s Queen Esther. Dozens of retellings of her story, including the procheese Kol Bo version, were written, distributed, and read in some European synagogues. Judith, following the model of many biblical heroines, was pious, brave, clever, and decisive. When her community of Bethulia considered surrendering to the harsh Assyrian general Holofernes, Judith acted. She prayed, bathed, dressed, and headed out into Holofernes’s camp and into his tent, carrying cheese and wine. And there, under a purple and gold netting that dripped with emeralds, he lay waiting, powerful in his opulence. After tricking Holofernes into falling asleep drunk on his beautiful bed, the pious seductress cut off his head with his own sword and returned home with the prize wrapped in opulent netting. With trickery, fierceness, and a bit of God’s help, Judith spurred her community into action. The Jews were saved, and peace was restored. But Judith’s story has faded from view. For all the Purim spiels filled with costumed Esthers that I’ve attended, I have never heard Megillat Yehudit read, either in its original form or in its medieval rewrite.

I’m struck, though, by the parallels between the story of Judith and what is, arguably, the most beloved contemporary children’s Hanukkah story, Hershel and the Hanukkah Goblins,written by Eric Kimmel and illustrated by Trina Schart Hyman. On the surface it’s a very different tale. First published in 1985 in the children’s magazine Cricket, Goblins tells the story of Hershel of Ostropol, who, by his wits and chutzpah and some help from God, defeats eight goblins, one per night, to chase them away and restore the Festival of Lights. One of the goblins says:

“We don’t allow Hanukkah. Not around here.”

“Is that so?” said Hershel. “Who’s going to stop me? A little pip-squeak like you?”

“I may be little, but I’m strong,” said the goblin.

“Really? Can you crush rocks in your hand?” asked Hershel.

The goblin laughed. “Crush rocks? You’re joking. Nobody’s that strong!”

“I am! Watch!” Hershel took a hard-boiled egg from his pocket and squeezed it until the yolk and the white ran through his fingers. “That’s how hard I’m going to squeeze you if you try to stop me from lighting these candles.”

The little goblin’s eyes opened wide.

Goblins feels deeply Jewish. Its sleepy shtetl setting is filled with lighthearted shenanigans that echo the Wise Men of Chelm stories. While the plot, according to Kimmel, comes from the Russian folktale “Ivanko, the Bear’s Son,” the character of Hershel of Ostropol was a legendary Jewish trickster. A real person, Hershel was born in 1757 in Balta and took his name from the town of Ostropolye, both towns in an area that is now part of Ukraine. After losing his job as a schochet for constantly joking and offending his employers, he became a court jester in the Hasidic court of Rabbi Barukh of Mezhbizh, the grandson of the Ba’al Shem Tov. Hershel was a well-known figure, and long before Kimmel chose him for Goblins, the character of Hershel was the subject of stories, plays, and even a radio show. For all its gleeful mayhem, Goblins echoes the story of Judith. Like Judith, Hershel finds himself in a moment in which the Jewish community is imperiled and unwilling to act. Pious, clever, and brave, he enters the synagogue, finds the enemy waiting, and, with trickery, fierceness, and a bit of God’s help, comes out the victor.

I like to imagine Goblins being read in synagogues with the earnestness and awe that Judith was once received. After all, on Hanukkah we remember the best of our folk—people who were pious, clever, and brave enough to enter the enemy’s tent with cheese and wine, boiled eggs and pickles—just for a shining, flickering, moment.

Suggested Reading

Hanukkah and State: The Hasmonean Legacy

The exchange between Rabbi Riskin and Rabbi Sacks on Jewish power and politics is illuminated by the history of Hanukkah.

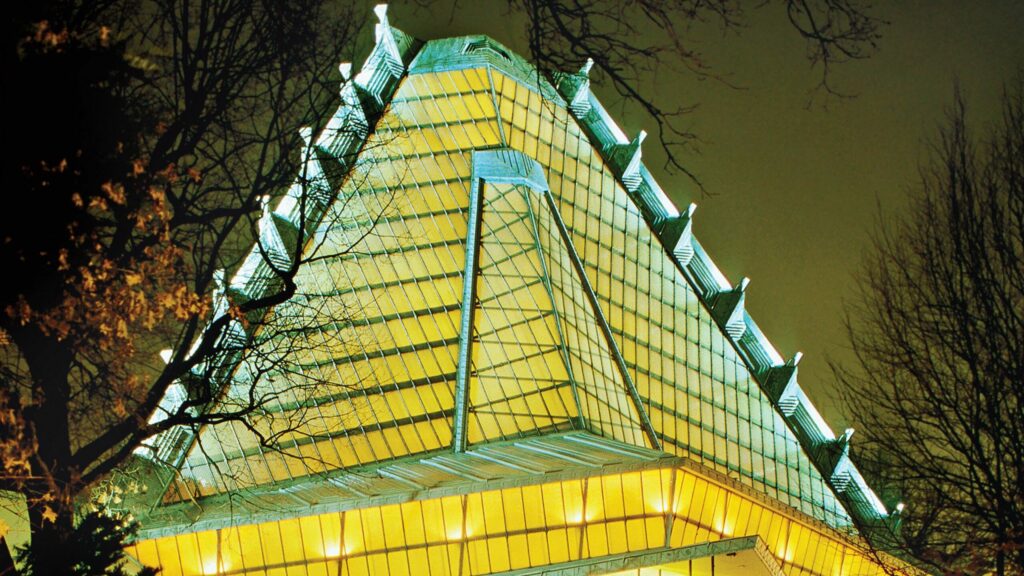

A Tale of Two Synagogues

Frank Lloyd Wright built a dazzling temple outside Philadelphia. Too bad he didn’t look closely at the synagogue of Gwoździec, Poland, built two hundred years earlier.

Faith and Miracles: Hasdai Crescas’s Passover Sermon

In Hasdai Crescas’s brilliant critique of Maimonides, he replaced the self-intellecting intellect that was Aristotle’s God with the God of Israel, whose essential nature, he argued, was one of unbounded and unfailing love.

A Dashing Medievalist

Ernst Katorowicz had great courage and old-world personal charm—his Berkeley students were mesmerized by him.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In