Yehuda Amichai and the Jerusalem of the Middle

Some evenings, in the still calm of Massachusetts, I stretch out on the couch and open Google Maps. My fingers glide over that gleaming digital globe, from North America to the Middle East, and once they find Jerusalem, I start running the regular route I used to take, before I went into this temporary exile in North America. I leave my home in the Katamon neighborhood, cross Emek Refaim in the German Colony, and come upon the overgrown field that the Jerusalem Municipality fenced off some two decades ago, planting a sign that reads: “Here will be built the Yehuda Amichai neighborhood.” Next to the sign, someone installed a placard with the lines to his ironic poem, “Mayor”:

It’s sad

To be the Mayor of Jerusalem.

It is terrible.

How can any man be the mayor of a city

like that?What can he do with her?

He will build, and build, and build.

(Translated by Assia Gutmann)

Despite successive mayors and endless building projects, the notional “Yehuda Amichai neighborhood” remains unbuilt. Yet the poem persists: as a monument to another Jerusalem; a forgotten Jerusalem; a secular, simple, and self-aware Jerusalem—a Jerusalem that included in its ranks one of the most important poets in the history of Hebrew poetry, Yehuda Amichai.

Like many of those associated with the city, Amichai, who would have turned one hundred this year, immigrated to Jerusalem from another place and with another name. It was in Jerusalem that Ludwig Pfeuffer, a young boy from Würzburg, Germany, became the poet Yehuda Amichai:

All the generations before me

donated me, bit by bit, so that I’d be

erected all at once

here in Jerusalem, like a house of prayer

or charitable institution. It binds. My name’s

my donor’s name.

It binds.

(Translated by Harold Schimmel)

The Israeli literary scholar Boaz Arpaly counted 220 times that Jerusalem is mentioned in Amichai’s poems, more than any other topic, even love. Amichai writes of the city in his classic style, mixing the personal and the collective while regularly alluding to the religious education he imbibed with his mother’s milk and which he turned his back on as a young man. His poems about the city give us Jerusalemites the ability to lead an almost normal life in a place that always seems on the verge of collapse from the weight of so much history and holiness: “The air over Jerusalem is saturated with prayers and dreams / like the air over industrial cities.”

Amichai wrote, “Jerusalem is forever changing her ways,” and he lived through several of the city’s many incarnations. He immigrated to Jerusalem during the Mandate period as a young teenager when, under the close supervision of the British, its atmosphere was thick with the national aspirations of Jews, Arabs, and Christians. After the War of Independence, Amichai built his home in the divided city, and even then, his desire for a life of normalcy was evident. In his poem “Jerusalem,” he described both sides of the border as longing for the same simple humanity:

On a rooftop in the Old City

laundry hanging in the late afternoon sunlight:

the white sheet of a woman who is my enemy,

the towel of a man who is my enemy,

to wipe the sweat off his brow.

In the sky of the Old City

a kite.

At the other end of the string,

a child

I can’t see

because of the wall.

We have put up many flags,

they have put up many flags.

To make us think that they’re happy.

To make them think that we’re happy.

(Translated by Stephen Mitchell)

Of course, in 1967 Amichai heard the call “the Temple Mount is in our hands,” but he also listened attentively to earlier voices:

The city plays hide-and-seek among her names:

Yerushalayim, Al-Quds, Salem, Jeru, Yeru, all the while

whispering her first, Jebusite name: Y’vus,

Y’vus, Y’vus, in the dark. She weeps

with longing: Ælia Capitolina, Ælia, Ælia.

She comes to any man who calls her

at night, alone. But we know

who comes to whom.

(Translated by Stephen Mitchell)

Unlike the Israeli mood of the time, Amichai’s poems from this period are not euphoric. “What do you know about Jerusalem,” he asks in this poem, which is titled “Jerusalem, 1967.” “You don’t need to understand languages; / they pass through everything as if through the ruins of houses. / People are a wall of moving stones.” And later: “Jerusalem stone is the only stone that can / feel pain. It has a network of nerves.”

Amichai made his home in Jerusalem’s Yemin Moshe, at a time when the neighborhood was still a dangerous borderland, “in no man’s land in the divided Jerusalem. / Our roof was hit, our walls wounded by bullets and shrapnel.”

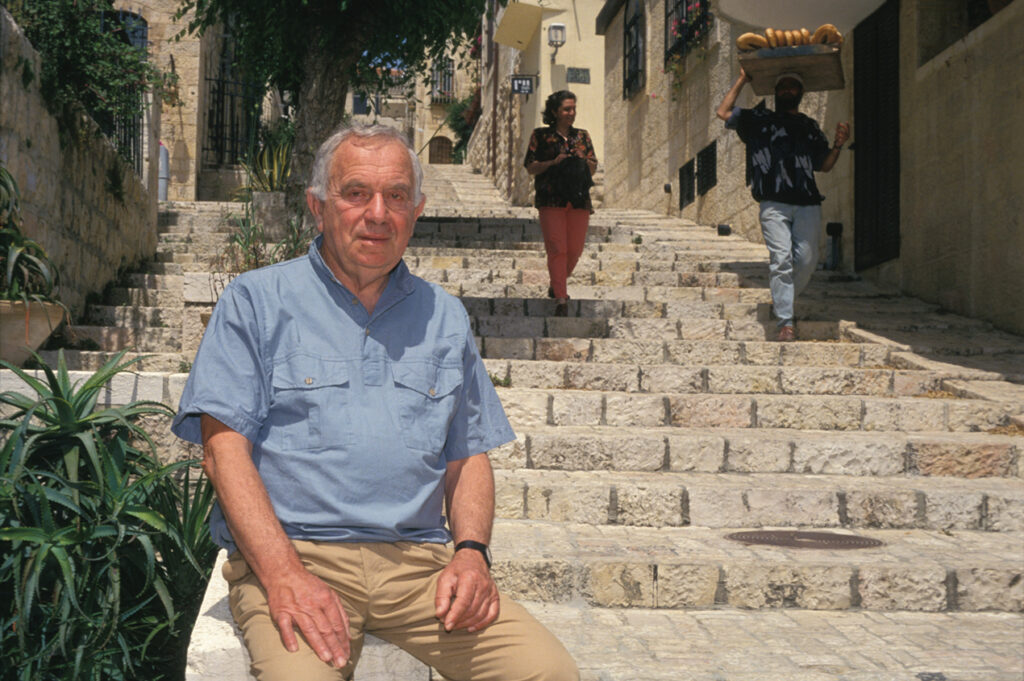

After the war, during a period of municipality-accelerated gentrification, the Mizrahi immigrants who had lived in the neighborhood during its hour of danger were forced to leave, and their homes were renovated. The bohemians arrived first, and when prices rose, they were replaced by rich Jews from around the world, whose houses with breathtaking views of Mount Zion and the walls of the Old City are left empty most of the year. Amichai was the very opposite; he was a man of the city who lived his life and conducted his affairs there. His sharpest irony was directed at the occasional visitors—for whom he served as a human backdrop, like the gates and the towers. His poem “Tourists” offers the sharpest articulation of what matters and what’s frivolous in Jerusalem. Although the first stanza is written in free verse and describes the hordes of tourists visiting the city’s many symbolic sites, its famous second part, written in lyrical prose, offers a parable:

Once I sat on the steps by a gate at David’s tower, I placed my two heavy baskets at my side. A group of tourists was standing around their guide and I became their target marker. “You see that man with the baskets? Just right of his head there’s an arch from the Roman period. Just right of his head.” “But he’s moving, he’s moving!” I said to myself: redemption will come only if their guide tells them, “You see that arch from the Roman period? It’s not important: but next to it, left and down a bit, there sits a man who’s bought fruit and vegetables for his family.”

(Translated by Glenda Abramson and Tudor Parfitt)

Redemption, according to Amichai, prioritizes the human over the mythical, the living person over the dead symbol—especially in Jerusalem, which is full of people and full of symbols. But Amichai does not seek to negate the meaning of symbols; he does not want to immigrate to secular Tel Aviv, and he does his shopping in the outdoor Mahane Yehuda market, not in the supermarket. He chooses to live in this overwrought city, to draw inspiration from it, to understand and honor it, but he chooses different priorities: “From man thou art and unto man thou shalt return.”

His last book of poems, Open Closed Open (1998), dedicates a final cycle to the city and tries again to understand, “Why Jerusalem, why me? / Why not another city, another person?” At the poem’s peak, Amichai succeeds in describing the city as it is, as he tried to live in it:

Why is Yerushalayim always two, the celestial and the earthly

I want to live in Yerushalayim the middle

Without banging my head up above and without stubbing my foot down below

And why is Yerushalayim in the language of pairs like hands and feet

I want to live in only one Yerushal

Because I am only one and not two

(Translated by Chana Bloch and Chana Kronfeld)

“Yerushalayim the middle” is not an expression of compromise, a middle path, or the manifesto of a centrist party. The poet wants to experience the prayers of the angels and the garbage collectors together on the streets. Amos Oz liked to say that he had two pens on his desk, one black and one blue. “I use one pen when I want to tell the government to go to hell,” Oz said. “I use the other pen when I want to write a story. And I never mix between them.” Amichai wanted to mix things up. He was fond of saying, “I sign my income tax forms with the same pen I use to write poetry.”

A man doesn’t have time in his life

To have time for everything.

He doesn’t have seasons enough to have

A season for every purpose. Ecclesiastes

Was wrong about that.

A man needs to love and hate at the same moment

To laugh and cry with the same eyes,

With the same hands to throw stones and to gather them,

To make love in war and war in love.

(Translated by Chana Bloch and Stephen Mitchell)

Examining the hundreds of metaphors and images Amichai used for Jerusalem could fill a composition notebook with endless contradictions: Sometimes Jerusalem is “a port city on the shore of eternity, the Venice of God,” and sometimes “Jerusalem is Sodom’s sister-city, / but the merciful salt didn’t have mercy on her / and didn’t cover her with silent whiteness.” In one poem, “Jerusalem is an unconsenting Pompeii,” while in another, “Jerusalem is like an Atlantis that sank into the sea: / everything there is submerged and sunken.” Amichai questions endlessly: Why Jerusalem, why not New York, why not London? And yet he always chose to live in “Jerusalem. An operation that was left open / The surgeons went to take a nap in faraway skies, / but her dead gradually / formed a circle, all around her.”

“I want to die in my own bed,” Amichai wrote. He got his wish, the celebrated poet lying in his Jerusalem deathbed twenty-four years ago. And even so, as the rabbis said of the biblical Jacob, Yehuda Amichai never died. When I am here, in the United States, it is easy to see that although the stock of Hebrew literature and poetry is crashing, Amichai’s value remains steady. His poems have been set to music and are regularly played on Israeli radio. His dialogue with the Jewish canon has granted him a place in contemporary Jewish prayer books, and his love poems are sent on WhatsApp as love letters. The poet Mark Strand once asked, “How else can you explain the fact that there are young poets today in the United States, for example, who are influenced by Amichai and [Vasko] Popa more than by T. S. Eliot, Wallace Stevens, or their successors in American poetry?”

For more or less the same reasons, however, Amichai’s prestige among Israeli elites has diminished. He is too accessible, too simple, a poet who wrote to be translated. And his central sin: he was too successful. The Israeli literary republic loves its poets poor, rejected, and undecipherable. But Amichai’s position is guaranteed: On my last visit home, on an evening stroll in the Hinnom Valley, I sat in front of the walls of the Old City and saw groups of tourists, Israelis and foreigners, and their guides held a Bible in one hand and a book of Amichai’s Jerusalem poems in the other.

I was named Amichai after my grandfather, Amishadai, but there was a time when I told girls whom I wanted to impress that I was named for the poet. In Jerusalem of the previous decade, that was worth a few points on dates. Like Amichai, I had also moved to Jerusalem.

As a child growing up in Ramat Gan, Jerusalem seemed to me like a long corridor built of stones, filled with haredim, Arabs, and government officials. I moved to the city after finishing yeshiva. It was in Jerusalem that I fell in love, got married, studied film. My children were born there, and it was there that I published three books of poetry. Yet I always felt that in Jerusalem, there was room for only one Amichai in poetry. Some time ago, I called an elderly beloved poet to invite her to read at an event in Jerusalem. “You told me that you’re Amichai from Jerusalem,” she said. “But that doesn’t make sense! Your voice is so young.”

Suggested Reading

A Complex Network of Pipes

You couldn’t know Yehuda Amichai without being struck by the casual way in which original and sometimes startling metaphors dropped from him in ordinary conversation. It wasn’t done for effect. It was just the way his mind worked. One thing made him think of another and what it made him think of was generally something that would not have occurred to anyone else.

A Walk in Jerusalem

Jews and Arabs live separately and are rarely friends, but they deal with each other constantly. The city can’t function otherwise. A walk in the Old City under a cloud of unease.

Pogrom: A Poem

Will the hunters come again to our abode tonight, seeking our souls with gun threats? Will they come quiet and furtive, until the crack of a shot cuts through the crickets? Perhaps they will arrive with a shofar blast like the lords of the land subduing the world, bringing their sons to teach them the wiles of war, carrying our…

Lives in Translation

The elegant essays in Hillel Halkin's new book are the fruit of a lifetime devoted to Hebrew literature.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In