Return to Me

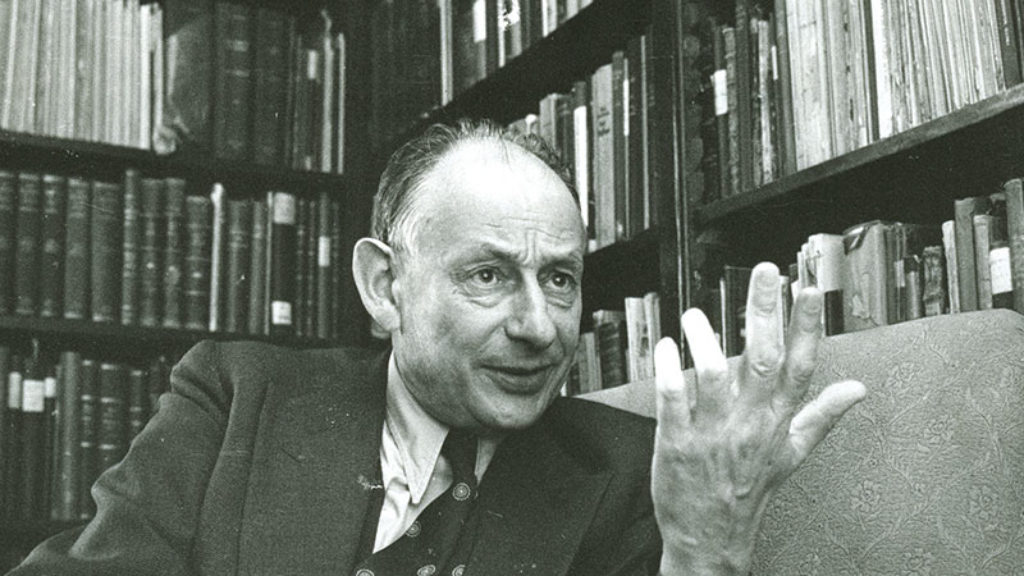

The Collected Plays of Chaim Potok, published this fall, comes as a surprise. It’s well known that Potok, who passed away in 2002, was a talented polymath. In addition to writing two bestsellers, The Chosen and My Name Is Asher Lev, along with a half dozen lesser known novels and a popular one-volume history of the Jews, he was a Conservative rabbi with a PhD in philosophy, an accomplished painter (he actually painted a version of his character Asher Lev’s blasphemous Brooklyn Crucifixion), and editor in chief of the Jewish Publication Society. But plays, too—who knew?

Potok will likely not be remembered as a novelist of Jewish ideas alongside Saul Bellow and Cynthia Ozick, but his best work, especially The Chosen, dramatized the struggles of the midcentury Jewish intellectual who aspired to excel in the modern world without compromising on the substance of traditional Judaism. This repeated theme recalls Potok’s own predicament—he was raised as an Orthodox Jew by immigrant parents before becoming a Conservative rabbi and aspiring modern novelist—and the narrative prose of his early novels had an urgency that his later stage dialogue does not match.

Potok’s stage adaption of The Chosen, written with Aaron Posner, does not quite recapture the emotional and intellectual intensity of the novel, which ends with a subtle goodbye between main characters Danny and Reuven, with much left unspoken: “Then he turned into Lee Avenue and was gone.” The play, in contrast, ends with a painful attempt to resolve everything with the compelling but overused rabbinic dictum: eilu ve-eilu divrei elohim hayyim—both these and these are words of the living God. And in case we didn’t quite get it the first time, Reuven repeats: “Both these, and these.” Most of the plays in this volume make one long for the novels they were based on.

Out of the Depths, the one fully original play in the collection, is an exception. It depicts the life of the great turn-of-the-century Yiddish writer S. An-sky, and it has real dramatic power. Born Shloyme-Zanvl Rapoport, An-sky authored the iconic and demonic play The Dybbuk. An-sky’s journey from traditional Jew to radical socialist and ultimately back toward affiliation with and advocacy on behalf of the Jews of his native Russia has been told before, but Potok turned it into the stuff of a Potok novel: an account of the unresolvable tension between traditional Judaism and something else—in this case, not art, psychology, historical scholarship, or East Asian religion, but a populist concern for the suffering of Russian peasantry.

Yet, unlike Danny or Asher Lev, this Potok protagonist does not teeter painfully between two irreconcilable worlds. Disgusted by the hypocrisy of the Bolsheviks and horrified by their persecution of the Jews despite their universalist rhetoric, An-sky comes back to the fold—decisively. To drive the point home, Potok depicts An-sky dying alone in a decrepit Warsaw lodging house, wrapped in a tallis.

In truth, the return might not have been as striking as Potok suggests. In a 2011 biography of An-sky called Wandering Souls (reviewed in JRB), Gabriella Safran argued that after An-sky’s communist adventures failed spectacularly, embracing Eastern European Jewry was simply another way for him to promote human rights.

And, admittedly, An-sky was uninterested in a conventional adherence to the Orthodoxy of his youth. As he put it: “I return on my own terms.” These would involve conducting a vast and unprecedented ethnographic study of Eastern European Jewry, making their difficult post-WorldWar I plight known to the world, as well as writing The Dybbuk. One of the repeated refrains of Potok’s play is derived from the Hasidic folk song “Mipnei ma” which is also the musical theme of The Dybbuk:

Wherefore, O wherefore

Has the soul

Fallen from exalted heights

To profoundest depths?

Within itself, the fall

Contains the ascension

Potok’s An-sky play still feels relevant today. The word for repentance in Judaism, teshuvah, translates literally as “return.” A secular Jew who becomes observant is deemed a ba’al teshuvah, literally a “master of return.” Or, in modern Israeli parlance, a chozer be-teshuvah, which we might translate as a “returner to returning.” (His Christian equivalent is described as undergoing conversion or, in certain circles, as being “born again”—both of which are more radical than returning.) The word teshuvah implies that no great break is needed on the way to spiritual renewal. Rather, moving forward is a process of getting back in touch with what was, in some sense, there all along, though what you return to might be neither the religion of your great-great-grandfather in the Pale of Settlement nor that of an affable Chabad outreach rabbi half your age. Return need not be to any discernible prior place at all. The Talmud writes that God created the possibility for teshuvah before creating the world (Nedarim 39b). Return is a state of mind.

This riff of return seems to be everywhere right now. In Jake Marmer’s fantastic new poetry collection, The Neighbor Out of Sound, for instance, the poem “Master of Return” reflects on Marmer’s own ba’al teshuvah experience:

It didn’t matter that I was returning

to a past

wholly imagined,

A life I had not lived.

Myth and autobiography overlap

Extemporaneously.

For Marmer, it turns out, this imagined past is a source of some dissatisfaction, but his characterization of religious return as a place where “myth and autobiography overlap” rings true.

Likewise, in Nicole Krauss’s Forest Dark,a successful young Brooklyn novelist named—surprise!—Nicole flees a failing marriage and finds herself in the rather unfamiliar culture of present-day Israel, contemplating Freud’s idea of the unheimliche, the uncanny. Despite the strangeness, Krauss’s protagonist realizes that she may be more linked with the Jewish collective than she understood back home in New York. Return, in her case, takes the form of exploring something mysterious and new.

Ruby Namdar’s The Ruined House (excerpted in JRB) pushes the motif of teshuvah even further. Namdar’s protagonist, Andrew Cohen, a successful and painfully narcissistic NYU professor, spends a year being haunted by visions of the ancient Jewish Temple. His last name notwithstanding, Cohen has as much familiarity with the Temple cult as any other secular Jewish academic enmeshed in his own cult of self-congratulation and gourmet food—that is to say, none. At a distant cousin’s son’s ostentatious Orthodox bar mitzvah, Cohen, who would normally turn up his nose at such an affair, finds himself oddly moved by something as seemingly innocuous as Hebrew words on the wall. Namdar writes (in Hillel Halkin’s excellent translation): “Something about it tugged at him, like a secret code that suddenly seemed painfully familiar . . . A strange, wistful longing overcame him, for what he didn’t know.” From the celestial songs of the Levites to the gruesome details of the animal sacrifices and the horrors of the Temple’s destruction, Cohen can’t shake visions of a past he never experienced. Namdar leaves open what all this will mean in the long-term for Cohen, though perhaps this uncertainty is also a feature of teshuvah. If it could be a permanent mode of being, why would we need to return to returning on the High Holidays, year after year?

There is a way in which the motif of return in modern Jewish literature undercuts what we might normally expect from a novel: a journey toward something new. Even for the great homecoming heroes—think of Odysseus and Huck Finn, for instance—it’s the journey, not the arrival home, that is the point. In contrast with the shimmering horizons that lie before the hero on his journey, home is a static thing. Teshuvah, on the other hand, offers the idea that the home to which one returns is endlessly dynamic, a source of vibrancy and depth. Perhaps An-sky sensed some of this—certainly in Potok’s version, anyway.

And since you’ve read this far, allow me to now introduce myself. I write, review fiction, teach English Literature to haredi college students, moderate suburban book clubs, and try to soak up Jewish learning when I can. I focus on the interactions between literature and traditional Judaism, including its texts and lived experience. I plan to use this platform to explore this interaction, which generates both harmonious intersections as well as tensions. My columns will explore contemporary and classical literature, and the occasional film or song, looking for intellectually and religiously meaningful insights into our cultural moment, as well as deeper truths that transcend it. Stay tuned in the coming months for discussions of feminism, Hasidism, Israeli television, and more.

Suggested Reading

Rachel and Her Children

Eternal Life is Dara Horn’s fifth novel, and like her others it crosses time and place to tell a transfixing, multilayered story that draws on Jewish texts and themes in a deep, witty, and immensely readable fashion.

Swimming in an Inky Sea

Ilana Kurshan, a hyper-literary, ideologically egalitarian, hopeless romantic (in her words), doesn’t fit the typical profile of a Daf Yomi participant.

Posthumous Prophecy

Milton Steinberg's unpublished novel about Hosea was forgotten for a long time. For good reason.

The Secret Metaphysician

While a new crop of biographies about Gershom Scholem all, in one way or another, seek to account for the great man's fascination, they are themselves evidence of Scholem’s ongoing allure.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In