Live Wire

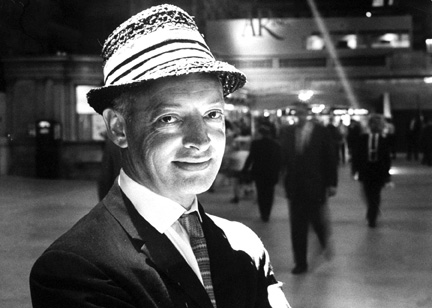

In his brilliant novella The Ghost Writer, Philip Roth sends his fictional alter ego, a young Nathan Zuckerman, on a pilgrimage to discuss the life and art of fiction with the eminent writer E.I. Lonoff, a character clearly modeled on Bernard Malamud (with a bit of Henry Roth thrown in). Eventually they come to their greatest contemporary. “The disease of his life,” Lonoff says, “makes Abravanel fly.”

I admire what he puts his nervous system through. I admire his passion for the front-row seat. Beautiful wives, beautiful mistresses, alimony the size of the national debt, polar expeditions, war-front reportage, famous friends, famous enemies, breakdowns, public lectures, five-hundred-page novels every third year, and still, as you said before, time and energy left for all that self-absorption. The gigantic types in the books have to be that big to give him something to think about to rival himself. Like him? No. But, impressed, oh yes. Absolutely. It’s no picnic up there in the egosphere. I don’t know when the man sleeps, or if he has ever slept, aside from those few minutes when he had that drink with me.

Abravanel is even more clearly Saul Bellow (with, maybe, just a bit of Norman Mailer thrown in), who, according to Roth’s recent chronicler Claudia Roth Pierpont, was not amused.

That his own fiction drew so heavily on his famously full and messy life has been both an obstacle and a blessing for Bellow’s biographers. On the one hand, it is hard to wring new insight from situations and events that Bellow described and thought through so deeply, repeatedly, and vividly in his fiction. On the other, it is easier to correlate the life and the art when the novelist in question approaches fiction as “the higher autobiography.”

Bellow’s first would-be biographer was Mark Harris, a novelist and acquaintance who approached Bellow in the mid-1960s and self-consciously imagined himself playing Boswell to Bellow’s Johnson. Bellow ducked and weaved for 15 or so years until Harris—who is now remembered mostly for his baseball novel Bang the Drum Slowly—finally published Saul Bellow, Drumlin Woodchuck. It’s an odd, charming memoir of his failures to pin down the elusive (and uncharmed) great author. The title is taken from Frost’s famous poem in which the drumlin woodchuck’s “…own strategic retreat/Is where two rocks almost meet,/And still more secure and snug,/A two-door burrow I dug.” A decade later, Ruth Miller, who had been among Bellow’s first students in 1938 and a friend ever since, tried to corner him with a study called Saul Bellow: A Biography of the Imagination. It wasn’t a great book; it was alternately chatty and ponderous, unsure whether it was a testimonial or a critical study, but it did hint at how much Bellow had drawn from his life for his fiction. They never spoke again.

Finally, in the 1990s, James Atlas was given full access to Bellow, his surviving family, friends, and papers (also his former friends, ex-wives, and enemies). Atlas succeeded in pinning Bellow down, and—to switch animals and famous poems (one Bellow once parodied in Yiddish, in fact)—when the novelist was pinned and wriggling on the wall Atlas alternated between shrewd insight and a competitive, sneering condescension. (Three examples of Atlas’ tone from early, middle, and late in the biography, taken almost at random: “Bellow’s onerous duties as a parent didn’t slow him down on the literary front,” “it is a novel of ideas to put it in the kindest light,” and, “After four marriages, Bellow was forced to acknowledge his shortcomings as a husband, but he continued to cast himself in the role of victim.”) Most recently and poignantly Bellow’s first son Greg has published a memoir, Saul Bellow’s Heart, which, while less than subtle in its literary readings, is nonetheless forceful in registering the human costs of his father’s art.

Bellow’s new biographer Zachary Leader is both authorized and judicious. His excellent biography is being published on the occasion of what would have been Bellow’s 100th birthday—he made it to 89—as is a new collection of his essays, lectures and reviews, There Is Simply Too Much to Think About, edited by Benjamin Taylor. The two books complement each other nicely and both should push the reader back to the great fiction, which is in the end their justification. (Taylor also put out a terrific collection of Bellow’s letters a few years ago, reviewed in these pages by Steven J. Zipperstein.)

Although Atlas did the initial spadework and interviewed many people who have since died, Leader has clearly done new and prodigious work in reconstructing and thinking through the details of a by-now familiar but still fascinating life, or rather the first half of it. Whereas Atlas took some 600 pages to tell almost the whole story (his Bellow: A Biography was published in 2000, five years before Bellow died), Leader takes almost 800 to get Bellow to the height of “fame and fortune,” after the publication of Herzog at the age of 49 in 1964. A second volume will carry Bellow through (to stop just at the highlights) a Broadway flop, a bitter divorce and decade-long alimony battle, Mr. Sammler’s Planet, co-editorship of several small literary magazines, journalism from Tel Aviv and Sinai in the midst of the Six-Day War, Humboldt’s Gift, the Nobel Prize, marriage to a glamorous Rumanian mathematician, then another bitter divorce, and his brilliant late-life renaissance culminating in Ravelstein, his novel about—an imprecise but unavoidable preposition with Bellow—his friend and University of Chicago colleague Allan Bloom. And, of course, his final, and finally happy, marriage to Bloom’s student Janis Freedman Bellow. It is hard not to be, like Roth’s Lonoff, overwhelmed just thinking about the roiling turmoil and gigantic achievements of such a life.

Saul Bellow was born in 1915, in Lachine, Quebec, just outside of Montreal, but Leader begins instead with his father Abraham and the family’s life in Russia. Abraham Belo (or Belous) was a volatile man, who had been briefly prosperous in Saint Petersburg before he was arrested for living there under false papers. In fact, the prosperity may have come from dealing in such papers (someone named “Belousov” was convicted of doing so around the same time, at any rate). Turn-of-the-century Russia is not Leader’s scholarly beat, but he is rightly more interested in the Russia of family lore that eventually made it into Bellow’s fiction than that of history. As Bellow once remarked “the retrospective was strong in me because of my parents,” so Leader moves swiftly from the Russia of Abraham Belo’s life to the old country that shadows his son’s fiction. Soon we are hearing of Herzog’s parents, who briefly lived like Bellow’s in a dacha in the old country, and of Pa Lurie in Bellow’s unpublished manuscript from the 1950s “Memoirs of a Bootlegger’s Son,” who was violent, “nervous like a fox,” and escaped from “Pobedonosteyev’s police” in Saint Petersburg, before eventually ending up in Chicago.

Bellow’s mother died when he was in high school. It hit him hard, and his relationship with his father was never easy. Although Bellow was a tough guy in print, Bellow’s father was a real tough guy, an operator who ended up running Chicago coal yards with his two older sons, and who could not understand his youngest or credit his success, even when it finally came. Of course things were not quite that simple; his parents had read Tolstoy and the other great Russian novelists (Dostoevsky was to become Bellow’s favorite), and, in an essay “On Jewish Storytelling,” included in There Is Simply Too Much to Think About, Bellow credited him with his sense of narrative, or rather with his sense that everything was a story. “My father would say, whenever I asked him to explain any matter, ‘The thing is like this: There was a man who lived . . . ’ [. . .] ‘There once was a widow with a son . . . ’ ‘A teamster was driving on a lonely road . . . ’” In Seize the Day, a beautiful novella published the year after Bellow’s father had died, the protagonist Tommy Wilhelm is asked if he loves his aged, emotionally remote father:

“Of course, of course I love him. My father. My mother”—As he said this there was a great pull at the very center of his soul. When a fish strikes the line you feel the live force in your hand. A mysterious being beneath the water, driven by hunger, has taken the hook and rushes away, writhing.

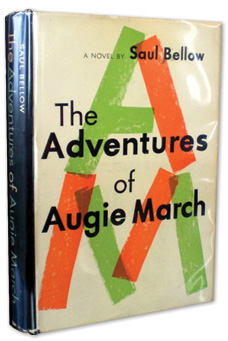

Although it took him a while to find it—he was in his late 30s and had already written two novels—Bellow’s first great subject was really his family and the Jewish Chicago in which he had grown up. He was in Paris on a Guggenheim fellowship, working on a depressing manuscript called “The Crab and the Butterfly,” in which two invalids philosophize in a hospital ward. As he later told Philip Roth: “I was walking heavyhearted toward my workplace one morning when I caught up with the cleaning crew who opened the taps at the street corners and let the water run along the curbs, flushing away the cigarette butts, dogs’ caca, shredded letters, orange skins, candy wrappers into the large-mouthed sewers . . . Watching the flow, I felt less lame, and I was grateful for this hydrotherapy and the points of sunlight in it—nothing simpler.” Bellow walked away from the street washers repeating to himself “I am an American—Chicago born,” at least so he remembered it in one version of the story (there were several and Leader quotes another variant). That is, he was suddenly writing the justly famous opening lines of The Adventures of Augie March:

I am an American, Chicago born—Chicago, that somber city—and go at things as I have taught myself, free-style, and will make the record in my own way: first to knock, first admitted; sometimes an innocent knock, sometimes a not so innocent.

As Leader says, this is when Bellow “found his voice as a novelist,” that distinctive freestyling prose that affects not to care exactly how its sprung rhythms and startling observations knock the reader. The last semi-grammatical phrase of that famous opening sentence, “sometimes a not so innocent,” has an unabashed Yiddish flavor, while the one that follows reminds you that Augie is as American as Huck Finn but not unlettered:

But a man’s character is his fate, says Heraclitus, and in the end there isn’t any way to disguise the nature of the knocks by acoustical work on the door or gloving the knuckles.

Bellow later spoke of his first two novels, Dangling Man and The Victim, as too proper, narrow, and constrained, an attempt, perhaps, to glove his knuckles or change the door.

Bellow’s not so innocent knock is generally taken as the moment when Jews barged into American literature without apology, but it wasn’t just a matter of voice. Augie March made an argument that the rough-and-tumble lives of Chicago Jews were as fit a subject for literature as any other. Standing there as the cleaning crew hosed down the Paris streets, Bellow says he thought of “a pal of mine whose surname was August—a handsome breezy freewheeling kid who used to yell out when we were playing checkers ‘I got a scheme!’” Charlie August, like his later fictional counterpart, Augie March, was a social type of the 1920s and 1930s that basically no longer exists in America, a poor immigrant Jew:

His father had deserted the family, his mother was, even to a nine-year-old kid, visibly abnormal, he had a strong and handsome older brother. There was a younger child who was retarded—a case of Down syndrome, perhaps—and they had a granny who ran the show. (She was not really the granny; she’d perhaps been placed there by a social agency that had some program for getting old people into broken homes.)

This recollection, along with that of the street cleaners’ “hydrotherapy,” comes from the wonderful (if fragmentary and repetitive) written interview that Philip Roth conducted on and off with Bellow in the last years of his life and published in The New Yorker after his death. Leader draws upon it in his biography, and it is now the last main selection in Taylor’s collection of Bellow’s nonfiction.

Bellow said that Charlie August lived next door to him on West Augusta Boulevard, which is an Augustinian coincidence, though not impossible, even if it’s an unlikely name for a Jew and the novel he ended up writing about him was cast as a kind of spiritual autobiography. He also said that he never knew what became of his pal, which is surprising, given that the book was a best-seller and the first chapters were a close, heartbreaking description of life in the March/August home. Wouldn’t Charlie/Augie, or someone who knew him, have called? Everyone else Bellow ever wrote about seems to have. Atlas took this all at face value in his biography, but there is no indication that he checked it carefully, and I wonder if the Marches were a “purer,” or at any rate more complicated, fictional invention than Bellow let on. Zachary Leader doesn’t say this, but on the other hand he doesn’t quite repeat Atlas’ claim that the actual Augusts had the same familial set-up as the fictional Marches. Whatever the case here, one has the sense that, as a biographer, Leader has complete control of his material and does not feel the need to let the reader in on every calculation, contested reading, and judgment made in the back room.

Bellow gave Augie March himself many of his own adventures and experiences, from teenage jobs and pranks to his visit to Leon Trotsky in Mexico, only to find the great man dying in a hospital from the wounds of his axe-wielding Stalinist assassin. And Augie’s streetwise older brother Simon so closely resembles Bellow’s older brother Maurice, down to the salacious details of a scandalous affair and love child, that it caused a rift between them. Years later, Maurice’s daughter Lynn said of her uncle “What kind of creative? He just wrote it down.”

This was a frequent complaint from Bellow’s friends, relatives, and acquaintances who did not realize that they were sitting for a portrait, or did realize but didn’t like the way it came out. Not that he was easier on himself. Herzog, which is probably Bellow’s best, most fully realized novel, is an account of an intellectual falling apart and pulling himself back together after discovering that his wife and best friend are lovers, which of course is what happened to Bellow.

As a truly literary biographer, Leader understands that what is important is how Bellow “wrote it down.” In the case of the humble, mostly Jewish cast of characters in The Adventures of Augie March, one can see him asserting their significance as subjects from the very beginning, conjuring up the world of his childhood as he sits at a writing desk in Paris. Grandma Lausch, Augie’s dictatorial matriarch who “wasn’t really the granny,” is described as “one of those Machiavellis of small street and neighborhood.” Augie’s description of his first great mentor, the devious crippled landlord-philosopher William Einhorn, sets out the theory behind this, what you might call Bellow’s American aesthetic:

He had a brain and many enterprises, real directing power, philosophical capacity, and if I were methodical enough to take thought before an important and practical decision and also (N.B.) if I were really his disciple and not what I am, I’d ask “What would Caesar suffer in this case? What would Machiavelli advise or Ulysses do? What would Einhorn think?” I’m not kidding when I enter Einhorn on this eminent list. It was him that I knew and what I understand of them in him. Unless you want to say that we’re at the dwarf end of all times and mere children whose only share in grandeur is like a boy’s share in fairy tale kings, beings of a different time better and stronger than ours.

Of Einhorn’s wife, he writes, “While Mrs. Einhorn was a kind woman, ordinarily, now and again she gave me a glance that suggested Sarah and the son of Hagar.”

There was no fairy tale time different and better and stronger than ours, or, even if there was, one is still obligated to live and reflect upon this age and one’s own people. Of course, Mr. and Mrs. Einhorn were also based on figures in Bellow’s life, in this case the parents of his close friend, later enemy (he was his divorce attorney) Sam Freifeld, though it was another friend Dave Peltz, not Bellow or Charlie August, who really worked for them. As Leader quotes Bellow on the relation between fact and fiction: “The fact is a wire through which one sends a current. The voltage of that current is determined by the writer’s own belief as to what matters, by his own caring or not-caring, by passionate choice.”

It is perhaps this emphasis on literary art as the jolt of observant caring that brings memories and facts to life—as “when a fish strikes the line,” and “you feel the live force in your hand”—that explains a puzzling feature of Bellow’s work. He was, without a doubt, the most celebrated American novelist of his generation, winning every prize and most of them two or three times. But as compositions very few of the novels really hold together. Narrators overshare, narratives trail off, seemingly stray characters take over, and the individual elements of a novel can feel curiously unbalanced for a writer of such manifest artistry. The individual parts—breathtaking descriptions, brilliant dialogue, utterly original turns of phrase—often seem greater than the whole.

Philip Roth, who is Bellow’s greatest champion, puzzled over this and once suggested that maybe he was in just too much of a hurry, which, in a way, is what Bellow himself wrote to Malamud in defense of Augie March: “A novel, like a letter, should be loose, cover much ground, run swiftly, take risk of mortality and decay.” He wasn’t aiming for a jeweler’s perfection but rather to capture and requicken messy, creaturely, contingent moments of human life, when a “mysterious being beneath the water, driven by hunger, has taken the hook and rushes away, writhing.” And he loved a good joke.

Bellow’s sense of the relation between life and literature and the purpose of the latter also helps to explain a curious feature of the non-fiction collected in There Is Simply Too Much to Think About. He was one of our great men of letters, the most discursive of fiction writers, a professor at the University of Chicago’s august Committee on Social Thought who seemingly gave lectures and wrote essays at the drop of an (elegant, rakish) hat, but he disdained literary critics and even the act of literary criticism. His own few reviews are more in the way of astringent encouragement of his peers. Reviewing Philip Roth’s now-famous first book of short stories, Goodbye, Columbus, he wrote “Unlike those of us who came howling into the world, blind and bare, Mr. Roth appears with hair, nails and teeth, speaking coherently.”

Critics, in short, ought to provide useful encouragement and then get the hell out of the way. This—as much as their differing temperaments and approaches—helps to explain the lifelong tension between Bellow and Lionel Trilling, the leading critic of his time, certainly among the Jewish intellectuals who came of intellectual age with Bellow in the 1930s. Invited to write a review of a new book of essays about Shakespeare’s sonnets for Trilling’s book club magazine The Griffin, Bellow writes “Perhaps the pleasure this collection gives me is in part the pleasure of seeing modern critics working hard in the 17th century. It is like having mischievous children at last out of the house.” Around this time, the mid-1950s, Leader recounts a story of Bellow greeting Trilling at a party: “Still peddling the same old horseshit, Lionel?”

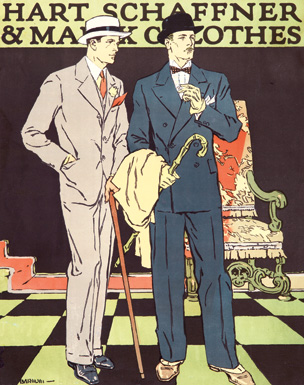

Calling his Bellow-character “Abravanel” was a good joke, though one doubts that either Philip Roth or Bellow would have recognized Don Isaac Abravanel if he had stepped out of Ferdinand and Isabella’s court and swatted them with a copy of his commentary to the Guide of the Perplexed. In the autobiographical lecture, which opens There Is Simply Too Much to Think About, Bellow wrote that he had tried “to fit his soul into the Jewish-writer category but it does not feel comfortably accommodated there.” And then comes the famous crack:

I wonder now and then whether Philip Roth and Bernard Malamud and I have not become the Hart Schaffner and Marx of our trade. We have made it in the field of culture as Bernard Baruch made it on a park bench, as Polly Adler made it in prostitution, as Two-Gun Cohen, the personal bodyguard of SanYut-Sen, made it in China. My joke is not broad enough to cover the contempt I feel for the opportunists, wise guys and career types who impose such labels and trade upon them.

Roth and Malamud also resisted the category, but both of them made the meaning of Jewish identity a central problem in their fiction in ways that Bellow did not. Although Bellow was, intermittently, a spiritual seeker, his sense of Judaism, or rather Jewishness, was visceral, not intellectual. When William Faulkner advocated, as chairman of a distinguished committee of writers empanelled by President Eisenhower, freeing the fascist poet Ezra Pound, who had been tried for treason but found insane, Bellow wrote to him:

Pound advocated in his poems and in his broadcasts enmity to the Jews and preached hatred and murder. Do you mean to ask me to join you in honoring a man who called for the destruction of my kinsmen? I can take no part in such a thing even if it makes for effective propaganda abroad, which I doubt . . . Free him because he is a poet? Why better poets than him were exterminated perhaps. Shall we say nothing in their behalf?

Bellow’s unapologetic moral clarity here (and not only here) derived, in part, from the same intuition as the famous opening of The Adventures of Augie March: that one can be Jewish and entirely American. His job was to make something of that. As he wrote in an introduction to an anthology of Jewish stories: “We do not make up history and culture. We simply appear, not by our own choice. We make what we can of our condition with the means available. We must accept the mixture as we find it—the impurity of it, the tragedy of it, the hope of it.” This was written in 1964, the last year Leader’s biography covers, but the sense of life and literature it expressed will carry his subject forward into the next volume. Bellow remained ineluctably Jewish and perpetually attuned to living in chaos.

This is the key to understanding his life, his live-wire approach to artistic creation, even his jokes. A friend of mine was invited out to dinner with Bellow sometime in the 1990s. At the restaurant, his wife urged him to order healthily to which Bellow replied “enough of this Tofu va-vohu!”—Tohu va-vohu being, of course, the book of Genesis’ description for the chaos out of which God created the universe.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Faith and Miracles: Hasdai Crescas’s Passover Sermon

In Hasdai Crescas’s brilliant critique of Maimonides, he replaced the self-intellecting intellect that was Aristotle’s God with the God of Israel, whose essential nature, he argued, was one of unbounded and unfailing love.

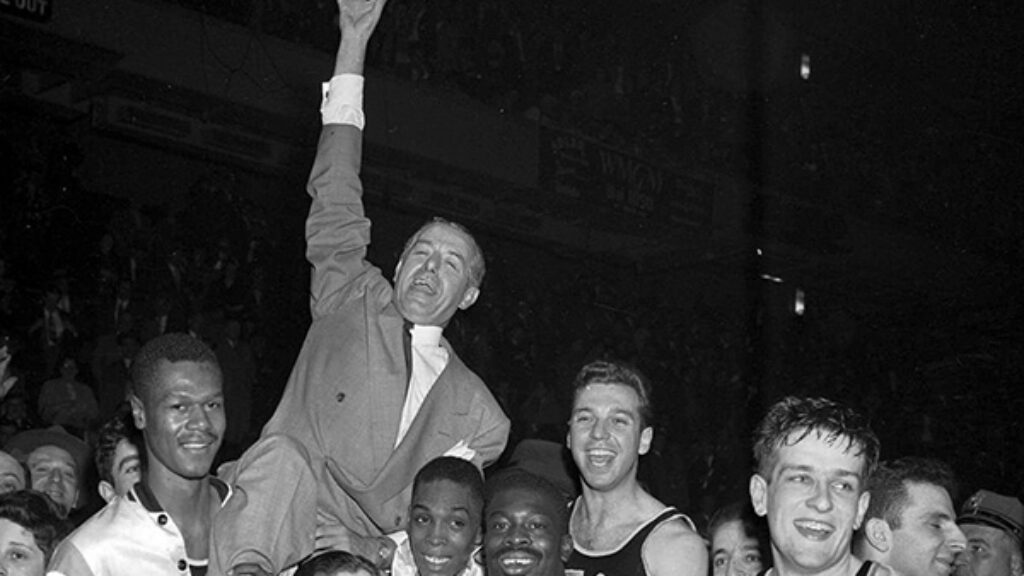

The Fix Was In

The 1951 basketball game that pitted CCNY, which fielded blacks and Jews, against the all-white University of Kentucky seemed less a meeting of schools than a clash of civilizations: old versus new, South versus North, prejudice versus tolerance.

Let the People of Israel Remember

The earliest literary commemoration of Zionism’s fallen heroes was a book entitled Yizkor, published in Palestine in 1911 by members of Poalei Zion (Workers of Zion).

Leviticus on the Fourth of July

Biblical narratives and imagery have played a surprisingly large, even outsized, role in the formation of the American national consciousness and institutions.

mikerol

Terriffic review.