You May View the Land from a Distance: Chaim Weizmann, May 1948

An excerpt from Chaim Weizmann: A Biography

On the fifth of Iyar 5708, Friday, May 14, 1948, four in the afternoon in Tel Aviv, nine in the morning in New York, the Provisional State Council convened in the Tel Aviv Museum to declare that an independent Jewish state would come into existence and that the council would then reconstitute itself as the Provisional Government of Israel. Chaim Weizmann, seventy-four years old, ill and both physically and mentally exhausted, received the news in his room at the Waldorf Astoria, which was kept dark because he could not bear the light. He sprawled on his bed, his face to the wall, as if he had just finished a marathon. His wife, Vera, entered. “The Jewish state was proclaimed in Palestine,” she told him. “The name is Israel. I would have preferred Judea.” Silence. Weizmann turned his face to his wife, who stood gazing into his eyes, waiting to hear what he would say. “Call Riva” were his first words. Riva Ziv, his secretary in New York, tiptoed in.

Weizmann, still prone, dictated a message to Riva without pause or revision, as if the words had long been ready in his mind. It was a brief letter to the men and women who at that moment in Tel Aviv were crossing the finish line in the long relay race of Jewish history and Zionism’s much shorter but arduous contest. He evoked the Jewish people’s two thousand years in exile, commended the forthcoming provisional government, and offered to be of service. His message was directed primarily at the citizens of the state that would be born the next day, especially those of the labor settlements. He also expressed his gratitude to Britain and to the mandate for their vision at the start—an allusion to the Balfour Declaration and to his role in it—as well as to the United Nations and the countries that voted in favor of partition. But what stood out was his aspiration for the establishment of a liberal democratic state, for coexistence and harmony among all the citizens of the new entity, Jews and Arabs, and for peace with Israel’s neighbors. Weizmann had not seen the text of the declaration that Ben-Gurion had delivered in Tel Aviv just a short time before Ziv took down his letter, but his sentiments were remarkably similar to those expressed in the Israeli Declaration of Independence.

The details began to fly in over the telegraph lines and were soon out in the press. In a telegram to the government and the citizens of Israel, Weizmann declared: “Renewed Israeli State is first historic bikurim [first fruits] after over eighteen centuries.” Visitors, flowers, telephone calls, and congratulatory telegrams began to stream in. Weizmann’s face remained inscrutable. According to Vera, he looked “worn out.” Herzl, the First Zionist Congress, and the Balfour Declaration were all mentioned in the declaration, but not Weizmann. He was chagrined not to find his name where he thought it deserved to be. A few months later, when the Declaration of Independence was formally inscribed and signed, he and others would lament that he had not been asked to add his name to it. But at the moment the declaration was made, all he wanted was recognition of the role he had played in history. In the meantime, he swallowed another painkiller, asked for a cup of tea, and complained to his wife.

In the torpor of his illness, he lost all sense of time, until, at six in the evening, President Truman sent a cable. Truman’s message acted like no medicine could. It notified him that the United States was granting de facto recognition to the state that had just come into being in a part of Palestine. Weizmann came to his senses and had a summary of his previous day’s letter to the president released to the press, focusing on his demand for recognition and for the end of the American embargo on arms shipments to the Middle East. He was back in the game.

On Saturday, a hotel employee presented him with a silver platter on which lay an envelope. Vera opened it and took out the telegram inside. Although the letters were Latin ones, the language was Hebrew. Chaim, with his poor eyesight, could not read the text, but he could make out the names of the prominent signers, including his colleagues and rivals Ben-Gurion, Sprinzak, Kaplan, Remez, Shertok, and Golda Myerson. Joseph Cowen was called in to read it. “We congratulate you on the founding of the Hebrew state,” it said. Then came the sentence Weizmann had been waiting for so hungrily: “Among those who are still with us today, there is no one who contributed as you did to its creation. Your position and your assistance at this stage of the struggle encouraged us all.” They concluded: “We look forward to the day on which we will have the privilege of seeing you as head of state, in days of peace. May we see you go from strength to strength.” Color immediately returned to Weizmann’s face.

But Chaim and Vera still didn’t celebrate. Visitors were kept out of the room. Vera carefully vetted the crowd gathering in the corridor, letting only a chosen few into the suite’s sitting room and none into his bedroom. A telephone call to the hotel office from an Associated Press reporter at nine thirty the next evening, May 16, brought the news that Weizmann had been elected president of the Provisional State Council. The reporter asked for a statement from Dr. Weizmann. Vera told him to call back later when Weizmann’s political adviser would be in. She put down the receiver, approached Chaim’s bed, and congratulated him. He asked what for. “You are the first president of Israel,” she told him.

He pondered the signs he had already seen—vague ones, to be sure—that he would not be left by the wayside. Following the message from the Mapai leadership and the notification of his election, he was so certain that he was being reinstated to his natural position as leader that his mood soared. That same evening Weizmann used the word “Israel” for the first time. He could not sleep. At 6:30 p.m., they ordered champagne and invited Cowan, Joseph Linton, and Abba Eban as well as Vera’s sister Rachel and her husband, Joseph Blumenfeld, who were then in New York. They made a toast to the State of Israel and its first president.

The new state’s flag was raised over his hotel. Everyone in New York and Washington was referring to him as President Weizmann. The fact that the nature of the post was not clear and that Weizmann had not yet been sworn in did not bother anyone. The Washington Post went so far as to explain that, in Israel’s case, the post of president of the Provisional State Council was equivalent to that of the country’s president.

Since Friday, the telegraph office at the Waldorf Astoria had been on the brink of collapse. Many of the people who had worked with Weizmann over the years sent their congratulations. Albert Einstein wrote to him in his unique way, resentful of their shared political rivals in the movement and sharp as a razor:

I have read with great satisfaction that Palestinian Jewry has placed you at the pinnacle of the new state and in doing so have rectified, at least in part, the ungrateful attitude they have displayed toward you and your achievements. The game the English are playing against us is a pathetic one and America’s attitude looks ambiguous to me. I am confident that our people will overcome this last great demon and that you will gain satisfaction at having created a happy Israel community.

President Truman was not one to worry about details. He and his aides forgot that he had only granted the new state de facto recognition and that this needed to be followed by formal de jure recognition. They immediately invited President-Elect Weizmann to make a formal visit to the White House. For Jews all over the world and in Israel, and for many non-Jews, Weizmann was the embodiment of the new State of Israel.

At three that afternoon, the Weizmanns stepped out of the Waldorf Astoria. An excited Vera reported in her diary that “we are accompanied or rather preceded by [a] police escort of motor bikes, who make an unholy noise like [an] air raid siren, and we go through all the red traffic lights. A special carriage [is] reserved for our party with a [special lounge] for Ch[aim] and myself.” When they arrived in Washington, they were greeted by the president of the District of Columbia Board of Commissioners, who granted Weizmann a key to the city. They set out for Blair House, the official residence for guests of the president. Great consideration was given to Weizmann’s medical condition. Dinner was kept small, and the address he was slated to give before a joint session of Congress, as was the custom for foreign heads of state, was canceled.

After twelve hours of rest and recovery, Weizmann received three senior American officials, all three of them Jews with close ties to the president, Felix Frankfurter, David Niles, and Jacob Robinson, to prepare him for his meeting with Truman.

Weizmann and Truman then met for the first time in public. Weizmann gave Truman a Torah scroll with an elaborate mantle and thanked him for his support. The two presidents then retired for a brief conversation.

Weizmann had not been briefed by the provisional government, but he acted on his remarkable political instincts (and perhaps also the advice of Frankfurter, Niles, and Robinson). He asked Truman to end the arms embargo that was blocking the new country from purchasing weapons and ordnance it desperately needed to fight the invading Arab armies, to credential the provisional government’s representative in Washington, and to loan the government $100 million for defense and to pay for reconstruction after the war.

President Truman promised to consider all three requests favorably. With regard to the loan, he said it would not be a problem—after all, Jews always repaid their debts. At the press conference that followed the meeting, Weizmann adeptly responded to this without making it an issue. “Jews always pay their debts,” he said, “but I’m not aware that they ever were owing anybody anything.”

For the first time, Chaim Weizmann had entered the White House through the front door, he and the country he represented, with all protocols observed.

Suggested Reading

History—and Israel—from the Outside In

Chaim Weizmann's outsider view of the Yishuv often led to conflict with the Zionist leaders based in British Mandatory Palestine. But it was precisely that perspective that present-day historians (and arguably Israelis) would do well to recover.

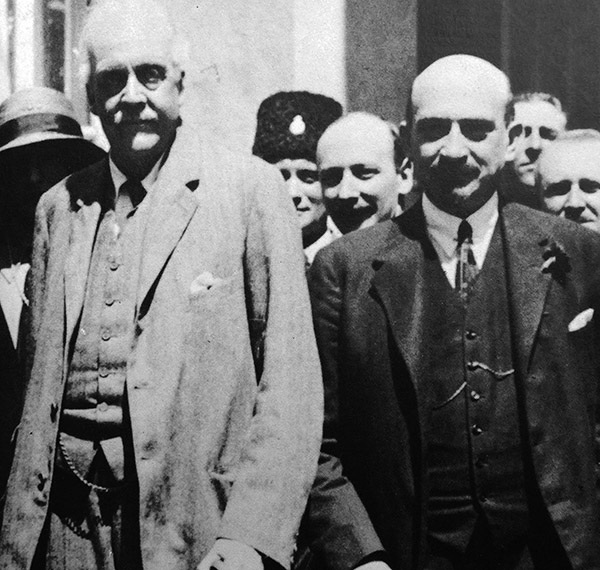

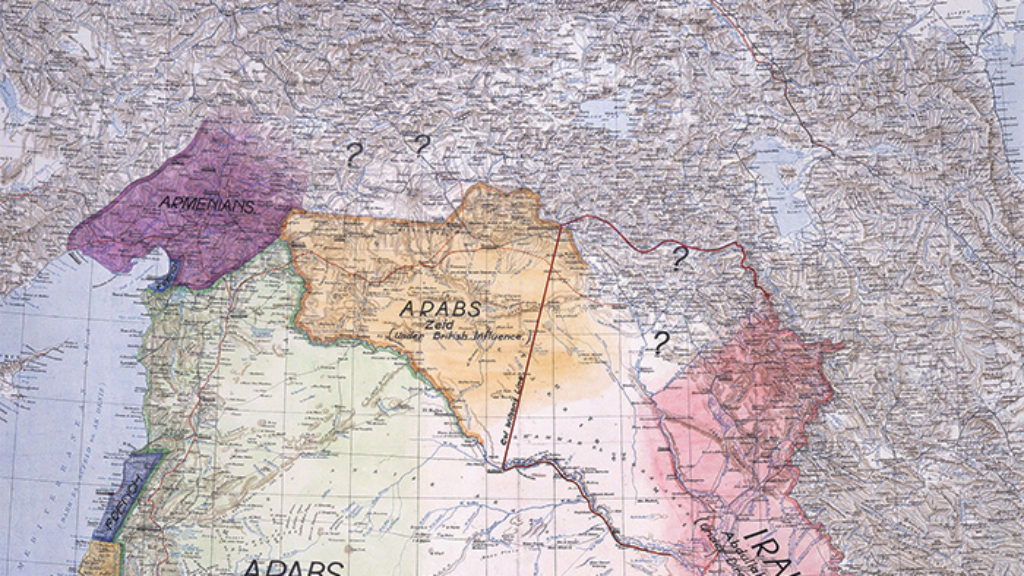

Chaim of Arabia: The First Arab-Zionist Alliance

Chaim Weizmann regarded his 1919 agreement with Emir Faisal as an epoch-making treaty. That didn’t turn out to be the case, but a century later an Arab-Zionist alliance may be reemerging.

Zion and Party Politics, 1944

In the summer of 1944 support for Zionism was transformed from a low-risk political gesture to a bona fide election issue. FDR was not pleased.

Theater and Politics in Oslo

Veteran Middle East negotiator Itamar Rabinovich gauges the distance between drama and diplomacy in his review of Oslo.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In