From Venice to Harlem

Not long ago, a workshop was a small factory where artisans gathered to produce objects such as picture frames or toy trains; today, a workshop refers to an assemblage of academics engaged in lengthy deliberation of a given topic, usually devoid of any tangible result. That’s nothing, however, compared to the ways in which the meaning of the word “ghetto” has shifted. Its widest currency these days is likely via hip-hop culture, where it indicates adjectivally the quality of street credibility in speech, manner, and dress. Admittedly, “the ghetto” as a noun still retains some of its earlier meaning as an inner-city neighborhood afflicted by poverty, blight, and crime. Yet a glance at the online Urban Dictionary, an addictive time-sink if there ever was one, indicates a number of further definitions, such as anything dilapidated, run down, or of inferior quality, or conversely “bling,” as in the sentence, “‘See how ghetto I look!’ Muffy said, as she put on her Gucci sunglasses.”

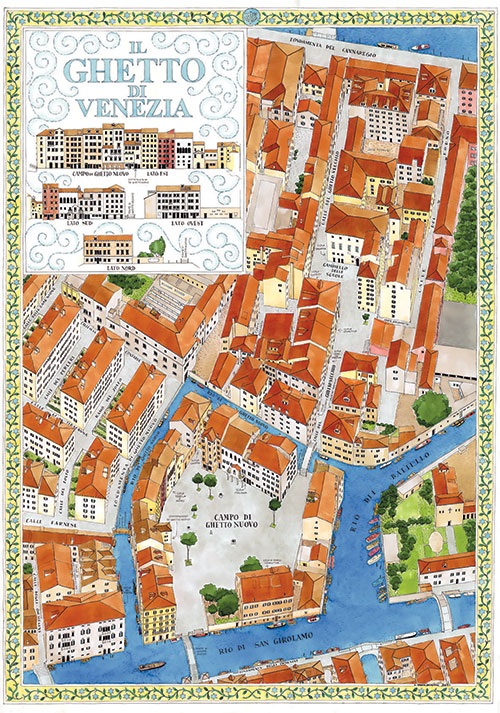

It is striking that none of the Urban Dictionary’s entries for “ghetto” refer to Jews. Of course, long before a ghetto was a confined and congested black residential quarter, it was a Jewish one. But even when it comes to its Jewish origins, as Daniel B. Schwartz shows in his excellent Ghetto: The History of a Word, it has proven a remarkably slippery concept. Does it refer, for instance, to the original Venetian ghetto, established in 1516 as a walled-off section of the city (eventually several adjacent areas) where Jews were compelled to live? Or is it better understood to refer broadly to the more or less voluntary Jewish residential quarters in medieval Europe and modern times, including such Jewish immigrant neighborhoods as London’s East End, New York’s Lower East Side, or Chicago’s Maxwell Street?

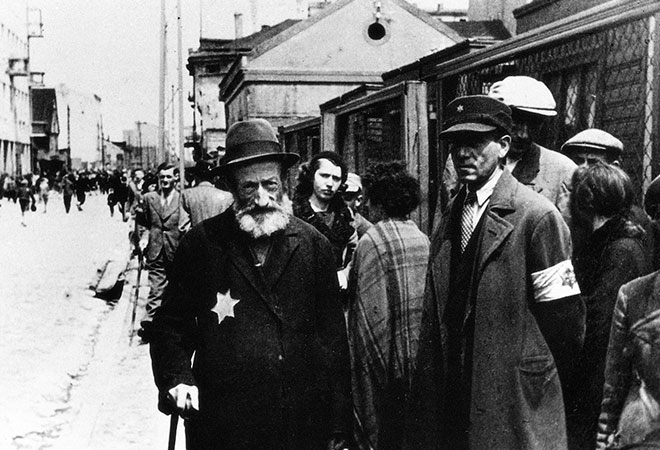

In mid-19th-century western Europe, “ghetto” began to acquire its symbolism as a blanket term for premodern Jewish life as a whole, not only in terms of living spaces but of religiosity, culture, dress, and the like. This usage was subsequently adopted by historians such as Salo Baron, whose classic 1928 essay “Ghetto and Emancipation” juxtaposed the evident benefits of the latter—individual civic and political rights—with the overlooked virtues of the former, especially Jewish self-government and the accompanying sense of communal belonging. In this usage, “ghetto” became a kind of red flag in arguments over the nature of Jewish modernity. Little more than a decade later, the term took on a far more sinister incarnation when the Nazis applied it to those urban prisons in cities like Warsaw and Lodz that functioned as torturous way stations to Jewish extermination.

In the face of such bewildering variety, Schwartz performs marvels of clarification and condensation in steering the reader through the labyrinthian twists, turns, and hidden alleyways that mark this terminological odyssey. He deftly traces the ghetto’s Italian origins, its subsequent 19th-century transformation into a metaphor for the bygone Jewish age (even when it was not yet entirely gone), its deployment by 20th-century American sociologists as a broad paradigm for the immigrant ethnic enclave, its usurpation by the conquering Nazi regime in Poland, and finally its appropriation and application to the American inner city, where its usage became an object of competition and a bone of contention between African Americans and Jews. Astonishingly, he demonstrates equal command of all of these disparate contexts.

Contention and confusion have surrounded the term “ghetto” from the very start. Most scholars today agree that Venice, from which Jews had previously been excluded, established the first true ghetto as a compromise, enabling the authorities to make use of their fiscal services (mostly lending money to the poor) while sealing them off from the Christian population residentially if not commercially. Most scholars assume the likeliest derivation of the word is from the name of the former copper foundry in whose surroundings the Jewish refugees were settled. Confusion arises from a competing popular etymology connecting “ghetto” to the Hebrew term for a bill of divorce, get. This notion originated in the Roman ghetto, not the Venetian one, but it is poignant, suggesting that Jews regarded their confinement as a forced separation from a formerly intimate partner. Schwartz, however, doubts the pervasiveness of such a sentiment, since prior to the 18th century, the ghetto’s Jewish occupants rarely complained about the institution itself, only the imposition of additional hardships (mostly limitations on their permitted livelihoods). At times, Jews even praised the ghetto as a divinely ordained vessel of communal purity and wholeness. As Schwartz tells us:

Verona’s Jews commemorated what they referred to as kenisat hatser ha-geto, the “entry into the enclosure of the ghetto” with a torch-lit procession of the Torah scrolls around the synagogue. They recited the Hallel prayer reserved for festive days of the Jewish calendar, along with special hymns.

If the first ghetto was, as Schwartz nicely puts it, “a largely tactical, temporizing response to an unforeseen and largely unwanted development,” subsequent Italian ghettos were the result of a deliberate policy of Counter-Reformation popes to herd Jews into constricted quarters where they were subjected to intense missionary pressure while Christians were supposedly protected from their corrupting influence. Even so, Jews were never hermetically sealed in their ghettos. More to the point, this enclosed space meant that while Jews in Western and central Europe were being expelled en masse by the 16th century, they still had a place in ghettos.

Nevertheless, by the 18th century, the onerous, indeed oppressive, character of the Italian ghettos had become undeniable and the object of Enlightenment rebuke. The walls of most northern Italian ghettos came tumbling down in the wake of Napoleon’s conquests, though some, like Rome’s, were restored after his fall. It was then, in the mid-19th century, that the Roman ghetto attained its reputation as an intolerable throwback to an era of obscurantism and clerical tyranny. Like those described by the American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, the Jews of Rome “lived in narrow streets and lanes obscure / Ghetto and Judenstrass, in mirk and mire.” The 19th-century German historian Ferdinand Gregorovius called these Jews “Rome’s only living ruins.” There they would remain, astonishingly, until 1870, when the completion of the Risorgimento, Italy’s national unification, finally dissolved the papal states and the ghetto within.

As the process of Jewish legal emancipation meandered forward in mid-19th-century central Europe, “ghetto” began to take on a broader meaning. Schwartz notes that both the German Jewish writer Berthold Auerbach and the Bohemian Jew Leopold Kompert, whose elegiac Aus dem Ghetto: Geschichten (From the Ghetto: Stories)was published in the revolutionary year 1848, made use of the term despite their awareness that the small-town Jews (Dorfjuden) they depicted weren’t residents of a ghetto, properly speaking. This deliberate blurring was intended, Schwartz explains, to make “ghetto” stand for a Jewish way of life that was rapidly disappearing in the face of modernization. Auerbach, Kompert, and others wished to memorialize the lost world of their fathers while also expressing confidence that they and their peers would take their rightful place in a more integrated modern society.

Once untethered from its original meaning and locale, “ghetto” was even applied to the vast territory of the Russian Pale of Settlement, home by the mid-19th century to nearly half of the world’s Jews. Schwartz traces this terminological expansion to a late 19th-century work by the American Reform rabbi David Philipson, who lamented that “in barbarous Russia, the medieval spirit still rules, and a Ghetto exists whose condition is more horrible perhaps than ever that of any Ghetto of earlier days.” In reality, the Pale was more than twice the size of contemporary France, and within this space, Jews comprised no more (and probably less) than 10 percent of the total population. Admittedly, they represented a far greater proportion of the Pale’s urban population, in total about 38 percent, and in many towns and cities as much as 50 percent or above. Yet what made the Pale seem a ghetto writ large was the fact that Jewish residential rights there were so heavily restricted. Not only were few Jews permitted to reside outside it, but even within, they were often required to remove themselves from border regions or were cleared away from parts of the countryside as a dubious safeguard against Jewish “exploitation” of the local peasantry.

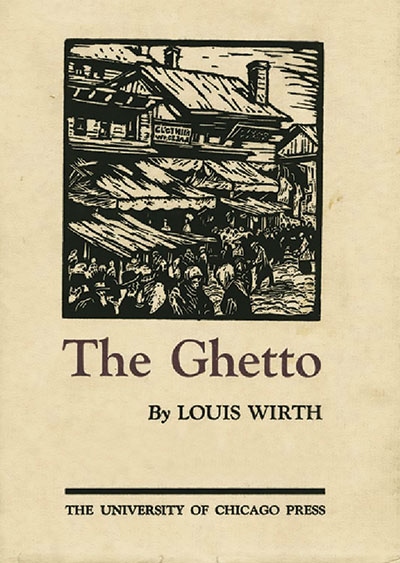

The Pale was the principal source of Jewish westward migration from the last quarter of the 19th century to the first of the 20th, populating immigrant neighborhoods from Vienna’s Leopoldstadt to New York’s Lower East Side, which now too became “ghettos.” Schwartz shows that some observers became fascinated with the ghetto as a kind of experiment in the processes of immigrant assimilation. Far from an insular island, the immigrant ghetto and its attendant institutions—ethnic newspapers, theaters, and lecture clubs—functioned, in the words of Yiddish daily Forverts editor Abraham Cahan, as “so many preparatory schools” for—and “stepping stones” to—an “English-speaking, self-educational society.” Taken up by sociologists associated with the University of Chicago’s Robert Park, particularly his Jewish student Louis Wirth, author of the 1928 The Ghetto, “this perception of the American ghetto as a ‘purgatory’ or ‘way station’ or ‘preparatory school,’” Schwartz notes, “would emerge in time as a master narrative of the immigrant experience.” Paradoxically, these sociologists found in the Jewish ghetto a veritable laboratory of engaged citizenship and a rehearsal stage for assimilation.

A key question posed by Park’s postwar successors was whether African Americans would proceed along a similar path. Black Americans’ Great Migration began in the 1910s, decades after the arrival of Jews from Eastern Europe and southern Italians. For scholars of American immigration like Oscar Handlin, writing in the early 1950s, the rise from the ghetto of preceding immigrant groups should have been a model for blacks too. Schwartz rightly observes that the application of “ghetto” to black neighborhoods like New York’s Harlem or Chicago’s South Side had an old pedigree, dating back at least to 1910, but he also notes that its usage expanded dramatically in the postwar decades. By then, the harsh ghetto image seemed far more characteristic of the experience of contemporary inner-city blacks than of what remained of Jewish life in the Lower East Side and even less so of the so-called gilded ghettos of suburban Westchester or the Five Towns.

Amidst the simmering urban unrest of the period, it was becoming increasingly apparent that blacks were not following in the footsteps of European immigrants and that for them, the ghetto was almost inescapable. As Schwartz details, rhetorical competition over who owned the term was now thrown into the pot of a long-simmering conflict between African Americans and Jews. As early as 1948, a young James Baldwin limned a harrowing portrait of the Harlem Ghetto in the pages of Commentary Magazine, depicting it not only as a theater of foreclosed hopes and stunted lives but also as a stage of bitter conflict between “Negro” residents and Jewish “small tradesmen, rent collectors, real estate agents, and pawnbrokers” who “operate in accordance with the American tradition of exploiting Negroes.” The fact that Jews had escaped their ghettos especially galled blacks, Baldwin claimed, in part because they suspected that Jews were no more authentically white than they were. Subsequent and more temperate discussions by social scientists and activists such as Charles Silberman, Kenneth Clark, and Bayard Rustin showed how misplaced was the Jewish-black analogy since color prejudice, postindustrial job loss, and an array of social pathologies had conspired to make the ghettos of America not way stations to the American dream but something closer to black Americans’ permanent prison.

Some blacks had adopted the “ghetto” label during and after World War II as a way of underscoring the hypocrisy of the United States fighting a war against a ghettoizing Nazi regime abroad while facilitating the growth of segregated black neighborhoods at home. In fact, of the many incarnations of the ghetto idea, none was as cynical as its Nazi usage during World War II. Previous ghettos, even at their most repressive and squalid, had still functioned as protective living spaces for Jews. The Nazi ghettos were the opposite.

In fact, as Schwartz shows, the Nazis employed the term only hesitantly, sometimes exploiting it for public relations purposes, as if they were merely reviving a venerable Christian institution, at others deploying it as a kind of justification for imposing ever harsher measures. Some Nazi leaders like SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich initially argued against ghettoization, fearing that ghettos were the Jews’ natural habitat from which they would only draw strength. At the same time, Schwartz poignantly explores Jews’ own struggles to come to terms with these new ghettos, with some finding solace in their presumed resemblance to medieval forerunners and others recognizing their murderous intent. Perhaps the ultimate conceptual reversal of the “ghetto” concept occurred with the uprising of the Warsaw Ghetto in the late spring of 1943, an event which gave birth to a novel connotation, that of the ghetto Jew as a symbol of heroic resistance. But which in the end was the “real” ghetto? If Schwartz’s book has a failing, it lies in hewing too closely to its subtitle, “the history of a word.” This method, which was inspired by Nietzsche and draws on the work of the literary scholar Raymond Williams and intellectual historians like Reinhart Koselleck, offers the virtue of demonstrating change over time by focusing on a single concept through its (sometimes radically) shifting meanings. But one must still explain why the term in question proved so resonant, fruitful, and malleable over such a long time and in the most varied contexts. Early on, Schwartz asserts that the idea of the ghetto “has been fundamental to the very definition of Jewish modernity.” But why? If “ghetto” became, as he writes, a “metonym” for the Jewish Old World, then why did it survive, thrive, and morph in the New World, to the point of spinning off entirely new and entirely non-Jewish meanings? Daniel Schwartz has written an accessible, rigorous, and supple history of a confounding and important term. But whether the word “ghetto” today expresses more than a provisional and contradictory set of meanings remains an unresolved question.

Suggested Reading

Unquiet Ghosts of the Ghetto

As we mark the 80th anniversary of the fall of Poland to the Germans in World War II, a new documentary gives a glimpse inside the Warsaw Ghetto.

A Book and a Sword in the Vilna Ghetto

If the destruction of Jewish culture and Jewish life were intertwined, then the reverse was also true: The rescue of books, manuscripts, Torahs, and so on was almost as much a form of resistance as the preservation of life itself.

Du Bois, the Warsaw Ghetto, and a Priestly Blessing

When the editors at Jewish Life asked the venerable civil rights leader W. E. B. Du Bois to speak about the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, they had no idea that it would lead to a priestly blessing.

Out of the Ghetto

Are they for the Jewish state or against? A new book from Israel distills recent scholarship on the haredim.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In