The Treasure of the Jews

In 1867, the Scottish adventurer John MacGregor descended a rope ladder into a subterranean tunnel by the walls of Jerusalem’s Old City. His guide was the famous British archaeologist Charles Warren, engaged just then in one of the first serious excavations of Jerusalem. Once underground, the men scrambled happily through the filthy shafts “like cats or monkeys,” peering into the city’s ancient layers, the walls slick with moisture and the floor soggy with sewage. “Once we have got down,” Macgregor wrote of the experience, “we can scan by the magnesium light a subterranean city, the real city of Jerusalem.”

That idea—that the real city of Jerusalem lurks somewhere beneath the actual city with its grocery stores, traffic, and inconveniently present residents—has been a powerful one since the mid-1800s, when the seductive aura of that real city began to draw a string of fascinating and often misguided characters with a Bible in one hand and a shovel in the other, looking for something beneath the surface. These are the stars of Andrew Lawler’s book Under Jerusalem: The Buried History of the World’s Most Contested City, a survey of some of the colorful and fraught episodes that have played out here underground over the past century and a half.

The idea of digging up Jerusalem caught on in Britain and elsewhere as science began to supplant religion in the nineteenth century and as some of the old preoccupations of Europe were dressed up in new rationalist clothes. Interest in the Jews’ ancient capital was transferred from the musty theology department to the new archaeology department, which was staffed by some of the same people.

Lawler gives us an excellent recounting of the 1865 creation of the Palestine Exploration Fund in London, where the founders included the naturalist Richard Owen, believed to have coined the word “dinosaur,” and the archbishop of York, who “called for a new crusade to rescue from darkness and oblivion much of the history of that country in which we all take so dear an interest.” Charles Darwin chipped in eight guineas. The explorers were inflamed by the possibility of grand findings from Jewish antiquity—palaces, figures, gold, the treasures of Solomon’s Temple!—to rival the ones from Egypt, Assyria, and Greece that were then filling up the storerooms of the British Museum.

Much of this betrayed a misunderstanding of Jewish history, as a few lonely souls knew even at the time. The archaeologist Austen Henry Layard, for example, pointed out that the Jewish aversion to graven images meant the expeditions were unlikely to find statues. Even at their height, the Jewish kingdoms of the Bible were small, and monumental treasures would be hard to come by. Although “some interesting fragments might be discovered, no series of sculptures such as those at Nineveh or Babylon could be hoped for,” Layard cautioned. No one listened, but he’d identified the key problem with much of the Holy Land archaeology enterprise. Using the Bible’s words to locate the monuments and treasures of the Jews misses the point: the words are the treasures of the Jews.

Nonetheless, off the explorers set from London, storming the alleys of the Old City and Silwan, tunneling beneath the paving stones and sniffing around the mosques of the Temple Mount, to the displeasure of Muslim authorities and religious Jews, setting the stage for an enterprise that has continued in different forms to the present. One digger, the dissolute aristocrat Montagu Brownlow Parker, arrived in 1909 armed with the work of an obscure Finn who believed his mathematical calculations based on Bible passages had decoded the location of the Ark of the Covenant. The excavation ended with the crew fleeing Muslim outrage to a ship sailing hurriedly from Jaffa. A New York Times headline announced that the Temple treasures were on board. A long modern tradition—credulous journalism reporting archaeological “science” that is actually laundered spirituality mixed with wishful thinking—had begun.

There is much to say about the days of Byzantine Jerusalem, or early Muslim Jerusalem, or the colorful and short-lived Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem, all of which have been excavated in recent decades. But these layers under Jerusalem are mostly overlooked in Lawler’s book in favor of more familiar fare: a recounting of the decades of Jewish-Muslim rivalry around the Temple Mount. This choice isn’t surprising, but it’s too bad, because it narrows the focus and places what could be a story about history and discovery into a predictable political context. Here archaeology takes a back seat to a narrative about the rival claims of Jews and Muslims, whom Lawler describes at one point as “Abraham’s quarreling children.”

By the end of World War I, he writes, “Yiddish-speaking Europeans” dominated Jerusalem, and “in many ways they had more in common with European Christian colonizers than with the Jews who had lived in Jerusalem for generations.” Whether you think the early Zionist pioneers fleeing pogroms had anything to do with European colonizers, they spoke Hebrew and tended to avoid Jerusalem. The “Yiddish-speaking Europeans” of the city at the time were still mostly impoverished ultra-Orthodox Jews who had nothing to do with European colonizers or with modern Zionism and its desire for a Jewish state.

Lawler also describes Israel’s Ashkenazi chief rabbi as “leader of the faith’s Ashkenazim” and his Sephardi counterpart as “leader of the Sephardim,”when both are actually government functionaries with no real following. And there are more serious missteps in the descriptions of Jewish history and practice, like the idea that there’s no material evidence for Judaism as a “distinct religion until about the first century BCE.” It is true that rabbinic Judaism crystallized in late antiquity as one of several rival versions of Jewish faith and practice, but all sprung from the Israelite culture whose ample texts and traces, including the Temple Mount, stretch over the preceding millennium. To leap to the idea that this “makes Christianity a younger cousin [of Judaism], but only by a century or so,” as Lawler writes, elides a great deal to make a questionable point.

These problems are linked to a more central one affecting many Western observers, with their narrative of a city “sacred to three faiths”—namely, a failure to understand the unique centrality of Jerusalem in Judaism or to admit that the city is of interest to other religions only because it was sacred to Jews first. It’s impossible to understand the city without grasping that Jerusalem has existed at the center of Jewish consciousness since Rome was a village on the Tiber and that it has that role in no other religion. Christianity cares about Jerusalem because Jesus and his followers were Jews who orbited the Jewish ritual center on the Temple Mount. Islam built the Dome of the Rock on the Temple Mount because that was the site of the Jewish temple. Both imperial religions have more important cities elsewhere but came here with architects and stonemasons to create a physical expression of a claim central to both—that they had supplanted the numerically insignificant but historically imposing natives of Judea. That’s the fact that exists “under Jerusalem.”

Under Jerusalem plays this down in favor of the idea that the Jews have only one story of three, and one they’ve probably overstated. For example, Lawler tells us that for several centuries before the 1800s, Christians, Muslims, and Jews all forgot Jerusalem, and “while the Talmud admonished the Jewish people not to forget Jerusalem, few actually paid a visit, much less settled there prior to the nineteenth century.” This misses that Jews from Yemen to the Yukon invoked Jerusalem and prayed to return in each of the three prayer services they conducted every day, which they recited facing Jerusalem, and also swore fealty to Jerusalem at the end of every Passover Seder and wedding. Given the difficulties, a remarkable number of Jews did manage to come throughout the centuries, and as soon as a Jewish national movement was created, it was called

“Zionism”—that is, “Jerusalemism.”

In one interesting quote in the book, Sari Nusseibeh, a prominent Palestinian intellectual and moderate, explains the lack of interest in archaeology on the part of Arab residents. “They know something is underneath, but they look upon themselves as a natural stage of evolution of that long history,” Nusseibeh explains to the author. “You will become another layer, so they have no interest in digging into that history; you are an outgrowth of what came before, but your interest is in yourself and your time.” I happen to think this is a lovely explanation, and true to a large extent; the archaeologist’s preoccupation with physical remains is foreign to many people of faith. But it’s not to be taken purely at face value. The aversion to archaeology is also related to the common, and politically dangerous, knowledge that if you dig past the city’s Islamic and Christian layers, what you’re going to find is Jewish.

“Like the strange concoction of broken stone beneath the city that can, at a moment’s notice, turn liquid, Jerusalem’s past is too fluid for any single narrative to contain,”Lawler writes, and this is true. The city’s history is often bastardized by politics or simplistic religious interpretations. What many Western observers don’t grasp, however, is that they, too, have their own distinct, recognizable, and subjective Jerusalem. Under Jerusalem very much operates in this Jerusalem, the same one you see in most news coverage. The lens through which this Jerusalem is seen involves misapprehending or purposely downplaying Judaism and its history, tiptoeing carefully around Islam, and remaining unaware of the cultural condescension embedded in the observers’ own Christian or post-Christian civilization.

Lawler’s book ends with the idea that Christianity and Judaism are actually “cousins,” and Islam just barely younger, meaning that everyone has the same kind of claim, and, anyway, the borders between the religions are mostly “illusory.” This idea—that all thought systems and cultures are interchangeable and everyone’s ideas equal—is a religious idea in itself, the product of a specific moment in Western thought and one that could use some more rigorous introspection from its adherents.

Andrew Lawler does his best to understand the motivations and prejudices of all the people poking around Jerusalem—except his own. It’s a missed opportunity in a work that contains much of value. The psychology and politics of Jerusalem excavation, whether archaeological or journalistic, offer a potentially rich vein of investigation. What on earth is everyone looking for? That would be a worthy inquiry, but it will await a different book.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Professor and the Con Man

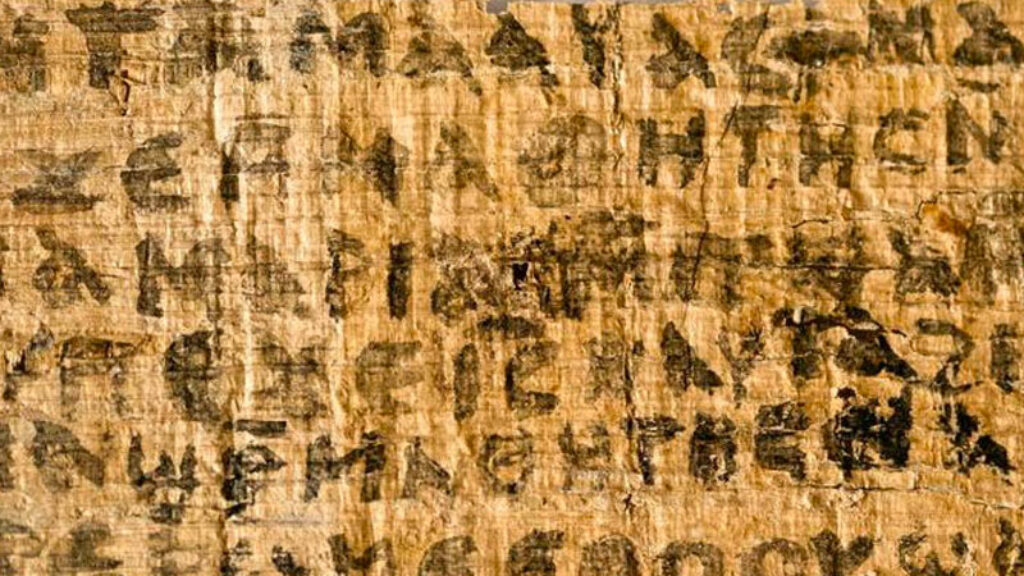

The saga of the papyrus that became famous as the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife began with an email sent to Karen King, a distinguished Harvard professor, in July 2010. The subject line read, simply, “Coptic gnostic gospels in my collection.”

Bling and Beauty: Jerusalem at the Met

In a new exhibit at the Met curators Barbara Drake Boehm and Melanie Holcomb wear their liberal hearts on their sleeves, imagining that Jerusalem's crowds might yet be resurrected as a convivial medieval pluralism.

A Complex Network of Pipes

You couldn’t know Yehuda Amichai without being struck by the casual way in which original and sometimes startling metaphors dropped from him in ordinary conversation. It wasn’t done for effect. It was just the way his mind worked. One thing made him think of another and what it made him think of was generally something that would not have occurred to anyone else.

Jerusalem Reconstructed

The Mendelsohns' converted flour mill on the outskirts of Rehavia became a cultural salon, with concerts and poetry readings.

judy snitzer

THANK YOU THANK YOU! Matti for writing a critical review of this book. Could you please try to get it published in more places. Everyone else I have read or heard via podcast just praises the book. You said some very important things about Judaism and Jerusalem. More than I was able to express myself. Especially appreciate your interpretation of why Muslims aren't interested in archaeology.

Margo Woll

I also agree with this review. As I was reading it I was very disturbed by some of his comments and personal theories. It is very much like some of the current news reported today, biased and inaccurate.