Nostalgia for the Numinous

In the beginning were the angry atheists: Sam Harris, Richard Dawkins, and their heaven-less hosts. Then came the response of the believers, of whom too there were many. After these books came more considered reflections, most from non-believers who nonetheless realized that religion spoke to something deep within the human condition. Among this third group were Jürgen Habermas’ An Awareness of What is Missing, André Comte-Sponville’s The Little Book of Atheist Spirituality, Alain de Botton’s Religion for Atheists, and the late Ronald Dworkin’s Religion without God. Perhaps most interesting was Hubert Dreyfus and Sean Dorrance Kelly’s All Things Shining, an out-of-the-box argument by two distinguished philosophers for a return to polytheism. Terry Eagleton’s new book Culture and the Death of God belongs to this category. His argument is simple: “Atheism is by no means as easy as it looks.”

We are meaning-seeking animals. And if we can no longer believe in God we will find other things to worship. Eagleton’s book is a brisk, intelligent, and provocative tour of Western intellectual history since the Enlightenment, understood as a series of chapters in the search for a God-substitute. The Enlightenment found it in reason, the Idealists in the human spirit, the Romantics in nature and culture, the Marxists in revolution, and Nietzsche in the Übermensch. Others chose the nation, the state, art, the sublime, humanity, society, science, the life force, and personal relationships. None of these had entirely happy outcomes, and none was self-sustaining.

The end result was postmodernism, a systematic subversion of meaning altogether. Postmodernism is Nietzsche without the anguish, tragedy, or will to power—all the things that made Nietzsche worth reading. Now, in place of the revaluation of values, we have their devaluation. We are surrounded by choices with no reason to choose this rather than that. Postmodern consciousness, in Perry Anderson’s phrase, is “subjectivism without a subject.” Eagleton calls it “depthless, anti-tragic, non-linear, anti-numinous, non-foundational and anti-universalist, suspicious of absolutes and averse to interiority.”

The result is that we are witnesses to the advent of the first genuinely atheist culture in history. The apparent secularism of the 18th to 20th centuries was nothing of the kind. God—absent, hiding, yet underwriting the search for meaning—was in the background all along. In postmodernism, that sense of an absence, or what Eagleton calls “nostalgia for the numinous,” is no longer there. Not only is there no redemption, there is nothing to be redeemed. We are left, Eagleton writes, with “Man the Eternal Consumer.”

There the story of the search for transcendence might have ended. But then came 9/11 and the realization that religion had not gone away after all. It had just signaled its presence in the most brutal fashion. “No sooner had a thoroughly atheistic culture arrived on the scene . . . than the deity himself was suddenly back on the agenda with a vengeance.”

The real trouble—and here Eagleton is surely right—is that the West no longer has a set of beliefs that would justify its commitments to freedom and democracy. All it has left is “a mixture of pragmatism, culturalism, hedonism, relativism and anti-foundationalism,” inadequate defenses against an adversary that believes in “absolute truths, coherent identities and solid foundations.” The West has, intellectually speaking, “unilaterally disarmed at just the point where it has proved most perilous for it to do so.” Eagleton regards this as an irony, but it is not. It is precisely the West’s loss of faith that made it seem vulnerable to its opponents. It is mostly the failure of postmodernism to speak to the most fundamental aspects of the human condition that has driven those in search of meaning and consolation into the hands of the anti-modernists for whom freedom and democracy are not values at all.

The substitutes for God turned out not to be substitutes after all. All the proposed alternatives to religion proved inadequate to achieve what the great faiths have done: “unite theory and practice, elite and populace, spirit and senses.” Rationalism devalued the emotions. Romanticism failed to check humanity’s darker drives. And culture was unable to bridge the gap between the elite and the masses.

What then is left? Readers of Eagleton will not be surprised to discover that the answer is unforthcoming other than a vague gesture to his lost but still nostalgically remembered faiths as a Catholic, then a Marxist (“a crucified body,” and “solidarity with the poor and powerless”). Nothing angers him more than a neo-conservative invoking religion for its character- and culture-strengthening properties: George Steiner, Roger Scruton, John Gray, and Alain de Botton all come in for Eagleton’s scorn. Yet it is hard to see what he is doing if not gesturing at the same sort of argument from a left-wing position.

Jews and Christians believe, in their different ways, that the Supreme Power entered history to redeem the supremely powerless. But if one does not believe this, then invoking God for political reasons is precisely what Eagleton accuses Machiavelli, Voltaire, Matthew Arnold, Durkheim, and Leo Strauss of doing, a strategy that he calls “unpleasantly disingenuous.” Eagleton is right to remind us that Judaism and Christianity have their revolutionary as well as their conservative moments. But we cannot feign faith if we lack it, and where in today’s deeply de-religionized culture will we find it?

Reading his book as a Jew, one cannot but feel that Eagleton understates the real pathos of the situation. For the post-Enlightenment search for a God-substitute, whether in reason, the human spirit, culture, or art, went hand-in-hand with the evolution of a new strain of one of the world’s most tenacious viruses, Judeophobia, or as it began to be called in the late 19th century, anti-Semitism. The epicenters of this deadly disease were the intellectual capitals of Europe—Paris, Vienna, and the University of Jena. You can catch at least a trace of it in most of the great philosophers of mainland Europe, in Voltaire, Fichte, Kant, Hegel, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Frege, and, most notoriously, Martin Heidegger.

This was the real refutation of Bildung and Sittlichkeit, “culture” and “sensibility,” as a substitute for religion: that more than a half of the participants in the Wannsee Conference that decided on the “Final Solution” carried the title “doctor,” that string quartets played in Auschwitz-Birkenau as a million and a quarter human beings—among them a quarter of a million children—were gassed, burned, and turned to ash. As George Steiner argued in Language and Silence almost half a century ago, civilization failed to civilize, and the humanities to humanize. And whereas the Catholic Church has tried to come to terms with its own history of Judeophobia, there has been almost no parallel self-reckoning on the part of secular philosophers as to how such a crime was possible, conceived, and enacted by the most self-consciously philosophical of Europe’s nations. (Jonathan Glover’s Humanity is an honorable exception.)

That tragedy has deepened in our time, as yet another new strain of anti-Semitism has emerged, substituting Israel for Jews and Zionism for Judaism. Jews find themselves for a third time denied the right to exist, first as a religion, then as a race, now as a sovereign nation. Once again not only has the academy by and large not protested, it has provided the new hatred with its most congenial home. In too many universities, campus life has become what Julien Benda called it in La Trahison des Clercs almost a century ago: a home for “the intellectual organisation of political hatreds.” Anti-Semitism is hardly the most pressing problem facing humanity, but over the centuries it has proved a reliable early warning of a civilization going wrong.

Can the West recover its faith? Livy said about 1st-century Rome that it had reached the stage where “we can endure neither our vices nor their cure.” Such is the degree of secularization among the West’s elites now that religious liberty itself is felt by many believers to be at risk. Having tried and failed to provide substitutes for religion, today’s public intellectuals have no new candidate to offer beyond the present mix of relativism, individualism, hedonism, and consumerism, which is neither elevating nor redemptive.

In global terms, the 21st century will be more religious than the 20th. In part this is because, after the failures of the God-substitutes, no other system remains as a source of meaning and consolation. In part it will happen simply because of demography. As Eric Kaufmann has documented in Shall the Religious Inherit the Earth? in most parts of the world religious practitioners have significantly more children than their secular counterparts. This really is the surpassing irony: Neo-Darwinian atheists risk extinction for the most Darwinian of reasons—their failure to hand on their genes to the next generation. In Europe, the epicenter of Western secularism, every native population is in decline.

But the religiosity likely to prevail in the future will not be the mild, latitudinarian God-as-an-English-gentleman variety. It will be passionate, zealous, and unforgiving, with none of the self-restraints we have come to associate with liberal democratic societies. Liberal theologies are everywhere in retreat. So too are traditional orthodoxies, committed to creative dialogue with the wider culture. As secular culture becomes increasingly hostile to religion, so religion becomes increasingly hostile to secular culture. And here lies the problem.

Enlightenment intellectuals and their successors did not, by and large, work within the world of faith itself even if they were themselves believers. They preferred to create neutral space—first science, then politics, then economics, then culture—systems that operated without religious presuppositions. There were liberal theologies aplenty, but none of them wrestled with the heart of darkness in many of the world’s great faiths.

The occupational hazard of monotheism is dualism: the division of humanity into the children of light and the children of darkness, the redeemed and the infidel. The result is that in the 21st century we will face a world of increasing religiosity of the most unreconstructed, pre-modern kind, whose devotees believe themselves to be commanded to convert or conquer the world. Too little has been done within the faith traditions themselves to make space for the kind of diversity with which we will have to live if humankind is to have a future. As religious groups turn inward under the impact of aggressive secularism, all that will be left will be the extremes.

Terry Eagleton has written a witty and insightful book, but the real work—discovering within the word of God for all time, the word of God for this time—remains. Our grandchildren will pay a heavy price if we fail.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

History with a Flourish

So much gets lost in translation—and to history—when household items, heavy with use, first assume the status of heirlooms and then land in museum vitrines, heralded as art rather than history.

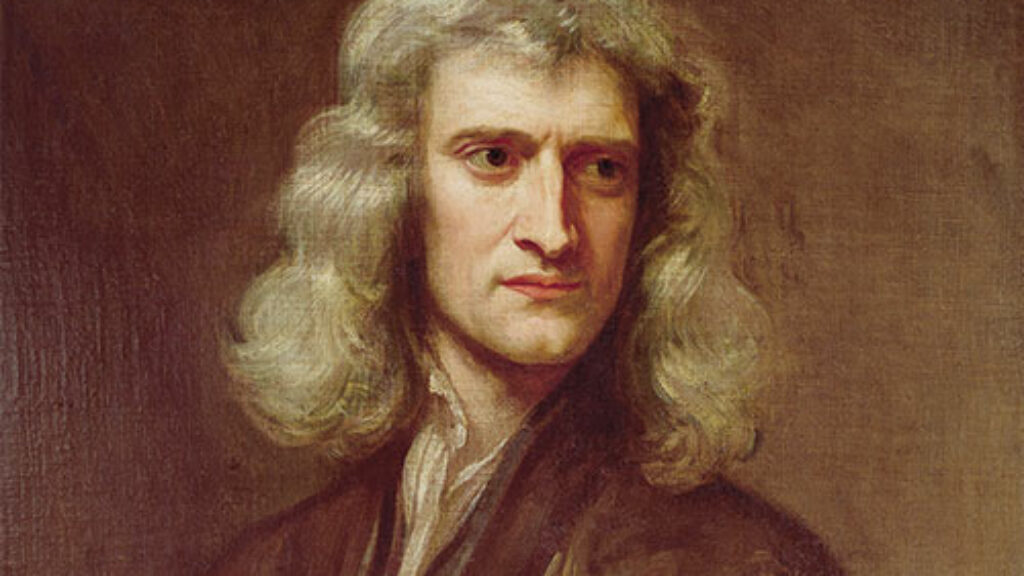

Maimonides, Stonehenge, and Newton’s Obsessions

It takes a bit of a genius to successfully study a genius, and in this case one must first master the millions of words Isaac Newton wrote about natural theology, doctrine, prophecy, and church history.

Strange Journey: A Response to Shmuel Trigano

Two historians challenge Shmuel Trigano’s analysis of anti-Semitic violence in France.

Life on a Hilltop

City on a Hilltop is superbly researched, altogether accessible, and will dispel many lazy stereotypes about the people whose story it tells. But it leaves out a lot.

witheo

“This really is the surpassing irony: Neo-Darwinian atheists risk extinction for the most Darwinian of reasons—their failure to hand on their genes to the next generation.”

No, but this is truly astonishing. Can anyone say such things, who happens to be Jewish by birth, rather than by conscientious choice? Or does one need to be rabbi Yaakov Zvi? Can Baron Jonathan Henry Sacks really make such claims, the former Chief Rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth? And get away with it?

The spiritual head, if not quite the religious authority, of the largest synagogue body in the UK and former Chief Rabbi of the Orthodox synagogues? Can he really resort to such a ludicrous proposition? As to suggest that ‘atheism’, whatever that is, could possibly be genetically inherited? With such authority?

Why, then being an ‘American citizen’ by accident of birth alone in like manner would fair make at once a dyed-in-the-wool patriot. Whether rabid Republican or demonised Democrat. Damned if I do and damned if I don’t. And all by virtue of descent and nought else?

N’ay, atheists’ are not so readily picked as would they grew on trees. Nor is ‘religion’ a something one can so confidently point a stick at. Not, at least, as to assert with such august authority that, “as secular culture becomes increasingly hostile to religion, so religion becomes increasingly hostile to secular culture.” Much too glib, I’m afraid.

This text deals too lightly with altogether too many ‘isms’. As though all of the substance is there plainly identified on the label. Obviously, ‘post-modernism’, as poorly as here expounded, can thus hardly be honourably defended. Any more than ‘polytheism’, ‘’secularism’ or Judaism’. Let alone ‘’the West’ or that ultimate of conceits, ‘the world of faith’. Where, in the name of your reputation, is that place? Other than woven into your text.

“All [the West] has left is ‘a mixture of pragmatism, culturalism, hedonism, relativism and anti-foundationalism.’” None of these ‘isms’ are ever seen paraded on the street. Wherever ‘the West’ might be.

If indeed it may be credibly stated that ‘the West no longer has a set of beliefs that would justify its commitments to freedom and democracy”, then surely that is for no better reason than that there never was such a coherent body as to entertain such fine luxuries.

Surely, sir, being Jewish, or even ‘religious’, whatever that might mean, must and always will remain a matter of individual conscientious conviction. Not ‘Darwinian’ genetic mutation. Failing which, no other ‘ism’ yet devised, I assure you, can ever sit credibly on any shoulders bereft of the will to put such on, and wear the same with pride. And dignity. For all thy scorn to the contrary.

Mandi Lea Abrahams

I wonder if you feel the same post-Trump.

ian

'The result is that in the 21st century we will face a world of increasing religiosity of the most unreconstructed, pre-modern kind, whose devotees believe themselves to be commanded to convert or conquer the world.'

Just because religious fanatics believe that the results of violence prove that their faith is justified against those who eschew violence and believe in the futility of waging war, does not prove that Atheists are wrong, merely that they value living on earth rather than existing in some mystical paradise in the mistaken belief that their particular deity will provide them with pleasures and benefits greater than they would have experienced on earth.

hbroder

R. Sacks could have offered a far better critique of Eagleton, one that might have followed an entirely different genealogy of postmodernism altogether, by tracing a phenomenology of religious practice(a la James, Husserl, Cohen, Soloveitchik) or of postmodern, and/or post-structuralist ethics (a la Levinas's critique of Heidegger, or Derrida's response to Levinas). The critique's theory, in a nutshell: There's plenty of Jewish, post-Enlightenment, and even pre/post-Platonic (midrashic) thinking in such genealogies, in their ability to both critique interiority as such and to discover consciousness of religion in various practices of exteriority.

clarkegary248

Great insight here- thank you. "Eagleton understates the real pathos of the situation"- wonderful assessment.

"Can the West Recover its Faith"- has resonance with the Indian Philosopher Vishal Mangalwadi (the Book that Changed Your World). I can't help but think that Lord Sacks and Mr. Mangalwadi could collaborate on ideas that might turn or at least stem the tide in the West.

gwhepner

UNDONE BY OUR VICES

Undone by our vices we aren’t able to endure

what by talking heads we are advised may the cure.

Most solutions offered for our malaise seem too iffy,

making men as livid as the countrymen of Livy,

although the one that’s offered by religion is assoc-

iated with high rates of reproduction. Its revival

is thought by non-believers to be both grotesque and gross,

yet they seem like the fittest for Darwinian survival.

[email protected]

YM Goldstein

We truly need Moshiach now

swhecht

Bravo to this review, so well conceived and written, and to JRB for publishing it. Reading this at the end of August 2014 it echoes even more than when it was published a few months before. An analogy for living without religion I considered partway through reading this review was: it is fascinating to learn of a man who has taught himself to eat neatly using only one hand and without utensils and we admire his achievement; it is not, however, at all pleasant to eat with all the others who try to imitate his feat. My only quibble with the review is why Durkheim was listed as one of those who invoked God for political reasons, but my bias in this respect is probably due to the strong substitute sociology has been for religion also. Thank you for this enlightening review.

jpnedved

Love this review of Eagleton's book. Very illuminating. The only thing I dispute is Eagleton putting Strauss in the list of those who are guilty of "invoking God for political reasons, a strategy that he calls 'unpleasantly disingenuous.'” No. 1, Strauss was not a rabbi, he was a political philosopher; No. 2, man IS a political animal. Above and beyond that, it pains me to read bilge putting Strauss in the atheist / nihilist camp. As a Catholic and avid Straussian, I am appalled that a man who can open the eyes of the blind (liberal) should be thus maligned. What I mean is, it is highly unlikely that I can reach a young modern liberal (who believes only in "science") with my Catholicism. But if I hand him "The City and Man" and ask him to start at p. 42, I can knock his socks off (or rather, have Strauss do so). Google (in quotes) "the world is the work of a blind necessity which is utterly indifferent as to whether it and its product ever becomes known" to read Strauss's unsurpassed description of the mindset and assumptions of modern science as a species of dogmatic skepticism whose hypotheses remains exposed to revision in inifinitum; how this "leads to the transformation and eventually abandonment of the questions which, on the basis of the primary understanding reveal themselves as the most important questions; the place of the primary issues is taken by derivative issues…”

Then, in his 1962 talk (to be found online) entitled "Why We Remain Jews - or Can Jewish Faith Still Speak To Us" Strauss compares religion to science, and does not find religion losing. He refers to the Aleinu prayer and asks, "What if it is a delusion?"

He writes:

“…delusion… We also say a “dream.” No nobler dream was ever dreampt. It is surely nobler to be a victim of the most noble dream than to profit from a sordid reality and to wallow in it. Dream is akin to aspiration. And aspiration is a kind of divination of an enigmatic vision. And an enigmatic vision in the emphatic sense is the perception of the ultimate mystery, of the truth of the ultimate mystery.

“The truth of the ultimate mystery - the truth that there is an ultimate mystery, that being is radically mysterious - cannot be denied even by the unbelieving Jew of our age. That unbelieving Jew of our age, if he has any education, is ordinarily a positivist, a believer in Science, if not a positivist without any education.

"As scientist he must be concerned with the Jewish problem among innumerable other problems. He reduces the Jewish problem to something unrecognizable: religious minorities, ethnic minorities. In other words, you can put together the characteristics of the Jewish problem by finding one element of it there, another element of it here, and so on. I am speaking from experience. I once had a discussion with some social scientists in the presence of Rabbi Pekarsky, where I saw how this was done. The unity, of course, was completely missed. The social scientist cannot see the phenomenon, which he tries to diagnose or analyze, as it is. His notion, his analysis, is based on a superficial and thoughtless psychology or sociology. This sociology or psychology is superficial and thoughtless because it does not reflect on itself, on science itself. At the most it raises the question: 'What is science?'

"Nevertheless - whatever may follow from that - I must, by God, come to a conclusion.

"Science, as the positivist understands it, is susceptible of infinite progress. That you learn in every elementary school today, I believe. Every result of science is provisional and subject to future revision, and this will never change. In other words, fifty thousand years from now there will still be results entirely different from those now, but still subject to revision.

"Science is susceptible of infinite progress. But how can science be susceptible of infinite progress if its object does not have an inner infinity?

"In other words, the object of science is everything that is - being. The belief admitted by all believers in science today - that science is by its nature essentially progressive, and eternally progressive - implies, without saying it, that being is mysterious.

"And here is the point where the two lines I have tried to trace [religion/revelation vs. modern science - JN] do not meet exactly, but where they come within hailing distance. And, I believe, to expect more in a general way, of people in general, would be unreasonable.”

Also, in 2006, Heinrich Meier published "Leo Strauss and the Theologico-Political Problem" which gives previously unpublished fragments of Strauss's thoughts about religion / revelation.

David Levine

Rabbi Saks will be MISSED. His presence was profound and needed. Who else could give Tony Blair and Prince Charles a Talmud lesson on an aircraft? Who else could garner the regard and respect of both Chasid and Reform? Who else could all of us rush to hear and listen to when his presence was announced? He should have had many more years with us and we with him!

David Levine

Rabbi Saks will be MISSED. His presence was profound and needed. Who else could give Tony Blair and Prince Charles a Talmud lesson on an aircraft? Who else could garner the regard and respect of both Chasid and Reform? Who else could all of us rush to hear and listen to when his presence was announced? He should have had many more years with us and we with him!

Mandi Lea Abrahams

Thank you for reposting this piece. The sudden loss of Rabbi Sacks has been a great shock but he has left us more than enough to think about and reflect on. There is such a huge task ahead to build a more humane world that we really can't be wasting time bickering.