The Jewbird

When Bernard Malamud died, in 1986, Saul Bellow composed a eulogy for the writer with whom he had been so often juxtaposed. The critical habit of viewing Bellow, Malamud, and the younger Philip Roth as a kind of literary consortium, a Jewish American all-star team, naturally irked all three of the men from time to time. It was Bellow himself who came up with the often-quoted quip that they were the Hart, Schaffner and Marx of American letters—a pointed joke, which suggests that Americans were more used to thinking of Jews as tailors than as contributors to American literature. For his part, Malamud was capable of envying Bellow’s success, which was an order of magnitude larger even than his own. Malamud may have won the Pulitzer and the National Book Award, but it was Bellow who got the Nobel Prize, as Malamud wryly observed in his diary in 1976: “Bellow gets Nobel Prize, I win $24.25 in poker.”

Yet in Bellow’s short eulogy, which can be found in his Letters, he welcomed the comparison with Malamud wholeheartedly:

We were cats of the same breed. The sons of Eastern European immigrant Jews, we had gone early into the streets of our respective cities, were Americanized by schools, newspapers, subways, streetcars, sandlots. Melting Pot children, we had assumed the American program to be the real thing: no barriers to the freest and fullest American choices.

It is easy to recognize in this description the Bellow who began The Adventures of Augie March with the triumphant words: “I am an American, Chicago born.” Bellow’s innate confidence—itself an American, Emersonian virtue—made it simply impossible for him to imagine that America and literature, which he loved so dearly, could refuse his love. This same confidence, the unquestioning self-acceptance that carried all before it, made Bellow’s feelings about Jewishness fairly uncomplicated, especially in the first part of his career. Jewishness was the condition of his existence, the environment in which he came to consciousness, intimately bound up with the helpless “potato love” that Bellow’s protagonists always feel for their family and early friends. If Jewishness was a problem, it was a problem for other people: In Bellow’s novel The Victim, it is the anti-Semite Allbee who is obsessed with the Jewishness of Leventhal, not Leventhal himself.

For Malamud, however, neither Americanness nor Jewishness were so straightforward. Far from feeling that he faced “no barriers to the freest and fullest American choices,” Malamud’s life can be seen as a desperate effort to vault the barriers that hemmed him in on every side. His early years were defined by his father’s business failures and by the mental illness of his mother: When Malamud was 13 years old, he came home to discover that his mother had swallowed a can of disinfectant in a suicide attempt. She survived, but had to go to a mental hospital, where she died two years later. As Malamud’s biographer Philip Davis and his daughter Janna Malamud Smith make clear in their books about him, these early miseries haunted the writer and his relationships for the rest of his life.

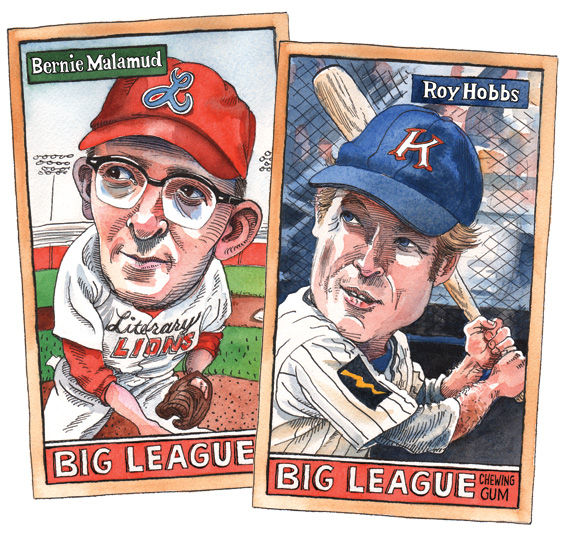

Perhaps the most significant thing in Malamud’s biography, however, is an absence. Born in 1914, he did not publish his first book, the baseball novel The Natural, until 1952, when he was 38 years old. For a man who already knew as a teenager that he wanted to be a great writer, this meant that 20 years, the prime of his manhood, were spent in frustration and distraction. The effects can be seen throughout his work of the 1950s and 1960s, now collected in two Library of America volumes edited by Philip Davis. (A third volume, covering the last part of Malamud’s career, is forthcoming.) During his twenties and thirties, Malamud taught high school at Erasmus Hall, worked for the Census Bureau, and took a few factory jobs. Time for writing was short, acceptances were few, and his first novel, The Light Sleeper, turned out to be a botch: After it was rejected by several publishers, he burned the manuscript. He drew on the experience in the 1953 story “The Girl of My Dreams,” in which the would-be writer Mitka does the same thing to his book:

In the late fall, after a long year and a half of voyaging among more than twenty publishers, the novel had returned to stay and he had hurled it into a barrel burning autumn leaves, stirring the mess with a long length of pipe, to get the inner sheets afire. Overhead a few dead apples hung like forgotten Christmas ornaments upon the leafless tree. The sparks, as he stirred, flew to the apples, the withered fruit representing not only creation gone for nothing (three long years), but all his hopes, and the proud ideas he had given his book; and Mitka, although not a sentimentalist, felt as if he had burned (it took a thick two hours) an everlasting hollow in himself.

By the time The Natural was accepted, by the legendary editor Robert Giroux, Malamud was teaching composition at Oregon State University, in the small college town of Corvallis. It was not a good job, and his negative feelings about both the school and the place are eminently clear from his novel A New Life, where they are satirized as nests of mediocrity and conformism. Still, teaching college was a step up from the life he had known in Brooklyn. On the cusp of 40, Malamud had escaped his family and finally established himself as a writer. From then on, his career would describe an upward arc. From Oregon he would move to Vermont, where he was a professor at Bennington College, and his stories and novels would earn steadily increasing acclaim (and money). In the end, Malamud’s was a success story—a life redeemed from obscurity and mediocrity by sheer talent and hard work.

The experience of prolonged struggle, the sense that the goal to which he dedicated his life might remain forever out of reach, shaped Malamud profoundly. Certainly it shaped the lives of his fictional characters, starting with Roy Hobbs, the baseball prodigy of The Natural. The Natural is in obvious ways an anomaly among Malamud’s books—a tall tale or folk legend, where most of his novels would be homely and demotic; a programmatically American subject, with not a single Jewish character to be found. The story regularly lapses from narrative into dream or vision, and Malamud enforces a mythical framework that gives the whole book a self-consciously literary quality, a willed alienation from reality that it shares with Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, published the same year. (If you don’t immediately grasp that the story of Roy Hobbs’s redemption of a failing baseball team is a modern recasting of the medieval Fisher King legend, Malamud nudges you along by naming the team the Knights, and its manager Pop Fisher.)

The Natural is a Jewish immigrant writer’s two-handed lunge for America, and while what Malamud came up with bears little relationship to the America he knew, the sheer effrontery involved energized his language in a way that he would never quite repeat. Here is Roy in his first professional at-bat, wielding his custom-made bat, his Excalibur, Wonderboy:

He couldn’t tell the color of the pitch that came at him. All he could think of was that he was sick to death of waiting, and tongue-out thirsty to begin. The ball was now a dew drop staring him in the eye so he stepped back and swung from the toes.

Wonderboy flashed in the sun. It caught the sphere where it was biggest. A noise like a twenty-one gun salute cracked the sky. There was a straining, ripping sound and a few drops of rain spattered to the ground. The ball screamed toward the pitcher and seemed suddenly to dive down at his feet. He grabbed it to throw to first and realized to his horror that he held only the cover. The rest of it, unraveling cotton thread as it rode, was headed into the outfield.

What rings truest in this passage, what would prove to characterize Malamud more than the poeticism, is Roy’s sense of being “sick to death of waiting.” One of the disorienting things about The Natural is that it is structured around a false start. When the book opens, the teenage Roy is riding a train to Chicago, where he is supposed to have his major-league try-out. Then, in a weird, abrupt, and dream-like scene, he is shot in the stomach by a madwoman, a serial killer of athletes whose presence in the story has just barely been prepared for by a brief allusion early on. When the novel resumes, Roy is in his mid-thirties and has somehow made his way back to the majors. But nothing can make up for the time he has lost, and his age means that his first season as a baseball player might be his last. We hear about Roy’s missing years only in hints, and the effect is as if he had been put to sleep, Rip Van Winkle-like, and then woken up almost two decades later. Malamud was deeply drawn to the situation of a man taking his last shot at happiness—a man who feels he has wasted the best years of his life.

That same feeling is shared by the protagonists of all the novels included in these two Library of America volumes. All of them approach middle age as if they had never been young, as if large parts of their lives had simply been deleted. Frank Alpine, the thief turned grocery clerk in The Assistant, feels like Roy: “I’ve been close to some wonderful things—jobs, for instance, education, women, but close is as far as I go. . . . Don’t ask me why, but sooner or later everything I think is worth having gets away from me in some way or other.” The very title of A New Life suggests that Seymour Levin, by following his creator and moving to Oregon to teach in a college, is making his last grasp at resurrection. (Unlike Malamud, Levin’s missing years are explained as the result of his alcoholism.) And in The Fixer, Yakov Bok gets himself into disastrous trouble when he, too, rebels against what he sees as a wasted life in the shtetl, symbolized by his inability to produce children with his wife, Raisl. “I’ve been cheated from the start,” Yakov grumbles. “The shtetl is a prison . . . it moulders and the Jews moulder in it. . . . I want to make a living, I want to get acquainted with a bit of the world.”

Yet none of these characters achieve the success that Malamud himself eventually did. Roy Hobbs makes it to the majors and becomes a sensation, only to lose everything when he agrees to throw a crucial game in exchange for a big bribe. Seymour Levin’s story ends on a desperate note, as he agrees to take in his married lover, with her children, even though he no longer loves her; his bid for a new life has landed him in a new kind of prison. And Yakov Bok finds himself literally imprisoned. When he moves to Kiev and tries to seek his fortune under a Gentile name, his identity as a Jew is discovered and he is scapegoated for the murder of a local Russian boy. Perhaps only Frank Alpine can be said to achieve “a new life,” though he does so by taking over the old life of the poor grocer Morris Bober, confining himself voluntarily to poverty and insignificance.

If Frank’s confinement looks to Malamud like a victory, rather than a defeat, it is because it is undertaken voluntarily, like monastic orders. Yet the form that this monkhood takes is, paradoxically, conversion to Judaism. The novel ends with Frank undergoing circumcision as a kind of inverse baptism: “One day in April Frank went to the hospital and had himself circumcised. For a couple of days he dragged himself around with a pain between his legs. The pain enraged and inspired him. After Passover he became a Jew.”

These are the book’s last words, and though abrupt, they nevertheless feel exactly right—the destination to which the whole story has been heading. Outwardly, that story is fairly undramatic, after the initial hold-up that brings Frank into Morris Bober’s store and life. The rest of the book chronicles Frank’s attempt to make up for the robbery by becoming Bober’s assistant and the consequent moral education that he undergoes. This is, in the novel’s terms, an education in Judaism: Morris lectures Frank about the majesty of the Law, which he construes not in religious or ritual terms but strictly ethically. And Morris himself is an ethical paragon, refusing ever to cheat his customers or take advantage of people, even though he is at the bottom of society’s pyramid. Becoming a good person, for Frank, means becoming Morris; and since Morris is a Jew, Frank must become a Jew as well.

Malamud’s definition of what it means to be a Jew is teasingly dialectical. One of the first things we learn about Frank is that he was raised in a Catholic orphanage, where he was exposed to miracle tales about St. Francis of Assisi that he has never forgotten. Becoming a Jew, for him, may be merely the name he gives to becoming a good Christian. Indeed, one of the main themes of the novel is that, while Morris’ Jewishness consists in fidelity to the Law—unswerving ethical behavior—Frank’s Christianity is expressed as Love, a matter of inwardness, conscience, and good-heartedness. That is why Frank can continue to hold the reader’s sympathy when he repeatedly backslides, committing crimes against the Bober family even as he claims to be helping them: stealing from Morris’ cash register, even raping his daughter Helen. These are sins, but Frank, as a Christian, comes to teach the Bobers (and the reader) the importance of forgiveness and mercy—exactly the lesson that Portia tries and fails to teach Shylock in The Merchant of Venice. At the same time, the Bobers are there to teach Frank the final earnestness of the Law—to help him to reach a state of moral perfection in which it is no longer necessary to be forgiven, because he no longer has the need to rebel.

In equating Christianity with Love and Judaism with Law, Malamud is of course reinstating an old and troublesome binary opposition—one that he learned not from Judaism, to which it is foreign (or at least as foreign as Paul), but from the Western culture and literature that shaped him. Yet at the same time, Malamud reverses the usual weighting of that equation, which makes Law benighted and Love superior. Both, he suggests in The Assistant, are necessary, but the Law is finally supreme: It is Frank who must become a Jew, not the Bobers who must become Christian. Jewishness, for Malamud, is less important as a religious or ethnic identity than as the password to a moral existence.

Here again, the contrast with Bellow is illuminating. If the first line of Augie March is Bellow’s credo, Malamud’s might be the last line of “Angel Levine”: “Believe me, there are Jews everywhere.” For Bellow, Jewishness was a condition of the self, but for Malamud it had a tendency to metastasize into the condition of the world—a moral and metaphysical quality that pops up in the most unlikely places. In addition to the Catholic Frank Alpine, among the Jews we meet in Malamud’s novels and stories of the 1950s and 1960s are the African-American angel of “Angel Levine,” an Italian aristocrat in “The Lady of the Lake,” and a bird in “The Jewbird.” In “The Jewbird,” indeed, the Jewish bird is persecuted unto death by the Jewish family with whom he seeks refuge. They are “anti-Semeets,” to use the bird’s Yiddishized pronunciation, not because they hate Jews—after all, they are Jews—but because they demonstrate the kind of cruelty and distrust of the Other that, to Malamud, is at the heart of anti-Semitism.

What Jewishness is not, for Malamud—what it cannot be, if it is to be a universal experience—is a concrete identity, or a specific religious tradition, or the history of a people. In a short memoir, “The Lost Bar-Mitzvah,” Malamud recalled that when he was about to turn 13, he petitioned his father for a bar mitzvah, but the family’s poverty and basic indifference to religion meant that it came to nothing. Instead, on his 13th birthday, his father put tefillin on him, had him recite some incomprehensible blessings, and it was all over: “Then he kissed me and said I was bar-mitzvahed, and he went downstairs into the store, to wait on any customer who may have appeared.”

As this anecdote shows, poverty, the grinding need to make a living, which Malamud writes about as well as any American ever has, was the bedrock reality of the family’s life. And because the writer came to know Judaism in no other form than the family, he ended up equating being poor and hardworking and terribly earnest with being Jewish. Contrast the list of non-Jewish Jews in Malamud’s fiction with the actual, ethnically and religiously, Jewish protagonists: Morris Bober, miserably poor but ethically sublime, and Yakov Bok, ditto. Notably, both these characters are directly based on real people: Morris on Max Malamud and Yakov on Mendel Beilis, the victim of a blood libel in 1913 Kiev. When Malamud searched the past for authentic Jews, what he found were tragic and serious men, usually victims.

At least, that is what he finds in his novels. But reading these Library of America volumes confirms the usual critical verdict that it is in his stories, rather than his full-length novels, that Malamud emerged as not just a talented writer, but a unique one. The best stories in The Magic Barrel (1958) and Idiots First (1963) avoid the earnestness and moralizing of Malamud’s novels. He achieves this by deflecting Jewishness away from actual Jews, who command his pity and respect, and toward “Jews”—angels, birds, mystic matchmakers—who are so flagrantly unlikely as to become comic. The collision of the surreally absurd with the tragically earnest is what defines Malamud’s fiction at its best. The opposites ought to cancel each other out, but instead they crazily coexist, and the leap of faith this demands from the reader helps to explain why stories like “Angel Levine” and “The Magic Barrel” seem like religious parables.

If, like Kafka’s parables or Hawthorne’s, they remain impossible to fully interpret, that is because all three of these writers knew what it meant to live in the grips of a religious tradition they no longer understood. Indeed, Malamud is one of the great writers of Jewish modernity precisely because Judaism has been severed, for him, from any determinate content. For exactly this severance from the past is the defining trauma of Jewish emancipation: The emancipated Jew finds himself answerable to a name that no longer corresponds to any definition.

Malamud’s mischievous contribution to this post-traditional tradition was to point out the contradiction involved in equating Jewishness with such universal identities. If Judaism is moralism, then why isn’t Frank Alpine a Jew? If it is chosenness, why isn’t Angel Levine a Jew? If it is victimhood, why isn’t the Jewbird a Jew? The outrageous answer Malamud gives is that they are: Everyone, pushed to the most extreme version of themselves, becomes Jewish. That this answer could seem plausible and meaningful, not just to Malamud himself, but to the large audience that acclaimed him, speaks volumes about the unique position of Jews and Judaism in post-Holocaust America—the objects of tolerance and pity and shame and envy and admiration, all at once, a condition never before experienced in Jewish history. But such a historical moment could not last forever, and while Jewish American literature continues to live, we will probably never again see a writer who conjoins, or confuses, the Jewish and the human as daringly as Bernard Malamud.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Exodus from Kishinev

From Kishinev, Moldova to Israel with Ukrainian Jewish refugees.

Redesecration and Solidarity in Greece

“Even if they vandalize the monuments one hundred times we will repair them one hundred and ten times,” pledged Yiannis Boutaris, the mayor of Thessaloniki, after the latest act of anti-Semitic destruction in the city.

Heart Work

As a successful young novelist, my father had literary friends who now included Angus Wilson, Frederic Raphael, John Wain, and Isaac Bashevis Singer. All came to tea in my nursery. Stanley Moss, my godfather, went on to make a fortune from art dealing.

Torah and the Thermodynamics of Life: An Interview with Jeremy England

Hailed by some as the next Darwin, immortalized as a character in a Dan Brown novel, Jeremy England discusses religion and science, his background, and his intellectual influences.

gwhepner

WHEN WHAT IS TRAGICALLY EARNEST AND SURREALLY ABSURD COLLIDE

From collisions between what is tragically earnest and surreally absurd

leaps of faith will generally provide just temporary relief,

since leapers in their flights of fancy, after hovering like a hummingbird,,

collide into reality from heights of their surreal belief.

[email protected]

gwhepner

WHY SO MANY JEWS ARE REFORMERS

Losing touch with Jewish tradition,

or not understanding it, writes Adam Kirsch, is the defining trauma

of emancipation, leading to loss of inhibition

that’s why so often an emancipated Jew turns into a devout reformer.

[email protected]