A Harem of Translators

Reviewing The Collected Stories of Isaac Bashevis Singer for The New York Times Book Review in 1982, Cynthia Ozick concluded by pointing out that Singer’s list of translators was so long (and it would only get longer) she could not possibly name them all. As if by way of explanation Ozick remarked that “Singer has not yet found his Scott Moncrieff,” referring to the preeminent translator of Marcel Proust. But, of course, Ozick knew that Singer didn’t want a Scott Moncrieff. In fact, he had first come to the attention of the American literary world when Irving Howe got Saul Bellow to translate “Gimpel the Fool” for Partisan Review in 1953. It was an extraordinary moment in the history of American Jewish letters, but Singer, who didn’t like to share the limelight, was looking for another kind of translator.

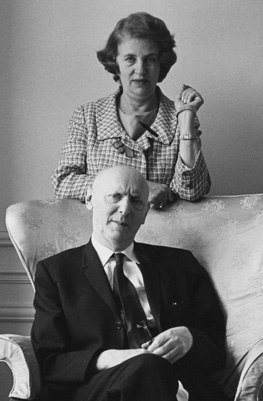

The Muses of Bashevis Singer, a new documentary directed by Israeli filmmakers Asaf Galay and Shaul Betser, is about Singer’s insatiable appetite for fame and for women, and about how he brought these together to solve his translation problem. The film includes interviews with several of Singer’s translators, two of his biographers (the French writer Florence Noiville and the late Yiddish scholar Janet Hadda), his proofreader and long-time mistress Doba Gerber, his Swedish publisher, a granddaughter, and a great-niece, among others. It also features footage from earlier interviews conducted with translators including Dorothea Straus, wife of Roger Straus, the chairman of Singer’s publishing house, Farrar, Straus and Giroux. After their sessions, Singer would pay Straus $71.03, saying “it’s a pleasure for me to make a check out to a rich woman.” Their relationship appears to have been chaste, but the film is full of accounts of Singer’s notorious philandering with translators and others, the abandonment of his young son and common-law wife, as well as his marriage to a woman who left her own husband and young children in order to be with him. If this were another author one might question such a heavy emphasis on the lurid details of the artist’s personal life, but Singer himself has testified that he had mixed “fiction with reality to such a degree that after a while I was bewildered myself. I didn’t know what is really autobiography and what is fiction.”

A quote from Singer that frames Galay and Betser’s film lays out the author’s approach to translation: “In my younger days I used to dream about a harem full of women; lately, I’m dreaming of a harem full of translators. If those translators could be women in addition, this would be paradise on earth.” Singer’s muses were women, most of them young, who were flattered to be taken under his wing and receive his attentions. He worked closely with them, often dictating his own translations so that they were closer to typist-editors than translators. Slavishly devoted, these women—and there were many—worked tirelessly under his tutelage. While it’s impossible to verify how many were also his lovers, Janet Hadda reports having heard from more than one of Singer’s translators that the author had slept “with all his translators except for me.”

Two women interviewed for this film recall being approached by Singer to translate his work. As Evelyn Torton Beck recounts it, “He asked me if I wanted to be his translator—it was like a marriage proposal.” Marie-Pierre Bay, who was responsible for bringing Singer to a French readership, remembers meeting the author over dinner with a group of people, at the end of which he “came up to me and said: you will be my translator.” In that moment, says Bay, “my whole life changed.” When Bay decided to study Yiddish (many of Singer’s “translators” did not know any Yiddish at all), Singer told her not to bother.

In fact, Singer insisted that all foreign-language translations of his work be based on the English versions. While Noiville chalks this up to an innocent desire for accessibility, the Hebrew translator Bilha Rubinstein insisted on working from the Yiddish after discovering that the English translations tended to sanitize the texts. Thus, shiksa became “village woman.” Similarly, the recurrence of the term nekeivos in Singer’s work, generally translated as “women,” loses the distinctly archaic (and misogynistic) flavor of the original.

In an interview that appeared in The Paris Review in 1968, Singer claimed, rather disingenuously, that since taking on the translation of his work he is able to “take care that I don’t lose too much.” What Singer actually did was craft translations that were deliberately unlike the originals, often in crucial ways. Though he insisted that, as someone who draws so heavily on folklore, he is a “heavy loser” in translation, the fact remains that many of the losses were engineered by Singer himself and designed to work to his advantage.

Indeed, as Hadda points out in this film, it was not for nothing that Singer was sometimes accused of betraying the Yiddish language, a theme explored by Cynthia Ozick in her satirical novella Envy; or, Yiddish in America. Centered around two characters who are thinly disguised versions of Singer and the Yiddish poet Jacob Glatstein, the story explores the envy inspired by the Singer character’s rise to fame among his cohorts who insist that his success in English amounts to a betrayal of Yiddish.

In the case of Singer, the famous Italian saying Traduttore, traditore (translator, traitor) takes on special urgency. Here was an artist who facilitated the translation of his work and then apparently preferred the translation to his Yiddish originals. But as Hadda points out, Singer had an eye toward English translation because he was “desperate for fame and he understood . . . nobody would become famous in Yiddish.”

Desperate for fame, hungry for women, Singer, who went on to win the Nobel Prize in 1978 and who is one of only two non-English writers (the other being Vladimir Nabokov) enshrined in the Library of America, refused to share his success with those who helped him achieve it. The best translator, he once said, is “both a sage and a fool.” Asked what he would want if he could have one wish, the author said he would ask God to be his translator. Maybe, though one doubts he would really want to give up his paradisiacal harem.

In her review of The Collected Stories, Ozick mentioned the “scandalous rumors” about Singer and his translators: “how they are half collaborators, half serfs, how they start out sunk in homage, accept paltry fees, and end disgruntled or bemused, yet transformed, having looked on Singer plain.” She imagines a Singer tale, set in Zamosc and called “Rabbi Bashevis’s Helpers,” that would tell the story of his many translators. In Galay and Betser’s film, Ozick’s wish has been realized.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Israelization of Judaism and the Jews of France

The increasing importance of Israeli culture for diaspora Jews has yet to be fully grasped. Nowhere is this more true than in France.

The Hasidim: An Underground History

David Assaf introduces us to Hasidic Rebbes who ride into small towns and take over. (If cowboys were Hasidim, this would be Deadwood.)

Kabbalah in 18th-Century Prague: A Response and Rejoinder

Sharron Flatto and Allan Nadler exchange views the Prague golem, Kabbalah, and Ezeliel Landau.

Scaling the Internet

September 11, 2001 proved Akamai's technology could withstand anything. Cruelly, inventor Danny Lewin was the first to die in the attacks.

rosenbergs1

Unfortunately, though well-meaning, this is an irony-deficient potboiler, film and review alike. "Singer’s insatiable appetite for fame and for women...". Tell us, are there succesful authors who have no appetite for fame and women (or men)? Unlike Norman Mailer or Bill Cosby, how many claims of abuse are there? And what is so terrible about using translators as collaborators?--or even "to make it in New York"? Singer's struggle to be relevant in English, on his own terms, needs more nuanced investigation. Translation is always a wonderfully fraught art, and speaking as Isaac's editor for a time, he was more obsessed with the art of the outcome than with the translator. Or perhaps translation and translator should remain distinct.

irwin12428

Oh, how sad that the odd widow of the great and neglected yiddish author Chaim Grade did not live to her meanspirited criticism of I.J. Singer justified. It would require another short story by Joseph Epstein on the disguised subject of Chaim Grade and his wife to do justice to

the memory of them all.