Quibbles

On March 17, 1955, Harry Austryn Wolfson walked into the Appleton Chapel of Harvard’s Memorial Church to preach a little sermon (or “sermonette,” as he called it) on Psalms 14:1, “The fool hath said in his heart, there is no God.”

The fool, who in the Scripture lesson this morning is quoted as saying to himself “There is no God” was not a fool in the ordinary sense of the term . . . He was a fool in the sense of being perverse and contrary. He denied what others affirmed . . . People, he knew, believed in God; and by God, he knew, they meant a Being above and beyond the world, the Creator and Governor of the world, a God who revealed Himself to men and told them what to do and what not to do . . . This, he knew, is what people believed in and this is what he did not believe in. And so honestly and bluntly he said to himself and to others, ‘There is no God’ . . . He did not start to quibble about the meaning of God. He did not offer a substitute God.

This is an unusual way to begin preaching, even at Harvard. The fact that Wolfson had, by that time, been Harvard’s most visible and distinguished Jewish scholar for decades, and still spoke with a strong Yiddish accent, must have made it even more surprising.

Wolfson proceeded to dismiss the work of medieval Jewish, Christian, and Muslim “scriptural philosophers” to whose “quibbles” he had devoted a lifetime of scholarship. He then turned to the prejudices of the theologians of his own time, whom he called “verbal theists.” “I wonder,” concluded Wolfson, “how many of the things offered as God by the lovers of wisdom of today are not again only polite but empty phrases for the downright denial of God by him who is called fool in the Scripture lesson this morning!”

What—aside from late-career second thoughts and innate chutzpah—inspired Wolfson to preach this sermon? Some of his targets were probably local: current and past Harvard colleagues. Among the empty phrases he mentions as being offered by contemporary theologians in place of God are “the principle of concretion,” a slogan of Alfred North Whitehead’s, and the “Ground of Being,” which, at the time, was particularly associated with Paul Tillich, who had just been brought to Harvard to occupy a distinguished University Professorship. Another one of Wolfson’s targets was probably the Protestant theologian Reinhold Niebuhr.

At “Wolfson’s Table” in the Faculty Club, his friend Morton White called those who took seriously Niebuhr’s pronouncements about the implications of man’s inherent sinfulness while ignoring their theological foundation “atheists for Niebuhr.” “The great political and economic issues of our time,” he later wrote, “are not likely to be settled by an appeal to a theological dogma . . . not shared by all honest and intelligent participants in the debate.” If Wolfson was provoked by what he read as empty phrases masquerading as deep thought about God, White was exercised by the idea that such thinking could go on to tell us anything deep about humanity.

I was reminded of this bit of mid-century intellectual history or, if you prefer, gossip, while reading John Patrick Diggins’ new book Why Niebuhr Now? just out from University of Chicago Press. (As is the way with book publishing, Yale University Press is coming out with a book by Charles Lemert called Why Niebuhr Matters later this fall.) Diggins, who passed away before the book was published, was a smart, contrarian American historian, and might have made a stronger argument if he had been able to see the book all the way to press, but as far as I can see, this is an argument on behalf of latter-day “atheists for Niebuhr.” In a typical passage, Diggins writes:

Niebuhr explained that man’s Fall precluded the possibility of any ultimate triumph. Were Americans to lose sight of the limits to their knowledge and power, they would fall victim to the sins of vanity and cupidity.

Elsewhere, he says that Niebuhr understood the Bible to be “an authentic mythology containing paradoxical wisdom” about how sin came into the world and the extent to which it can be overcome. Diggins contrasts this with the naïve optimism of John Dewey and those who came under his influence. I am inclined to grant Diggins that Niebuhr had a deeper understanding of the relationship between human limitations and freedom than Dewey did, and that it gave him a more realistic approach to the ironies of American history and the requirements of foreign policy. But this doesn’t amount to an argument that there is such a thing as authentic mythology or paradoxical wisdom, or that they ought to play a role in public policy (or that Niebuhr’s distinctively Protestant version of such wisdom is the right one).

In a massive new book of political and religious philosophy, Divine Teaching and the Way of the World: A Defense of Revealed Religion, Samuel Fleischacker argues for the wisdom and indispensability of traditional religion, and Judaism in particular. Fleischacker takes the title of his book from the famous saying in Pirkei Avot (Ethics of the Fathers), “Rabban Gamliel, the son of Rabbi Judah the Prince, says the study of Torah is good together with derekh eretz.”

The plain meaning of this is that it is good to divide one’s time between study and gainful employment, but as Fleischacker notes, derekh eretz literally means the “way of the world,” and connotes good manners or common human decency. Drawing on Enlightenment philosophers, especially Kant, together with a somewhat idiosyncratic reading of rabbinic texts, he argues that “there can be no proper devotion to or interpretation of divine teachings independent of a commitment to ordinary human decency, but also that divine teaching can offer something to a secular ethic that it needs, but cannot itself provide.”

This claim sounds ambitious, but is, perhaps, not quite as bold as it sounds. In the first place, it would appear that “divine teaching” covers a wide array of texts and non-texts. In fact, although he makes some cogent points along the way, it isn’t clear to me that Fleischacker tells us what makes a teaching divine. Moreover, his argument turns out to be that such teaching—whatever it is—does not and cannot add anything to our knowledge of ethics, politics, art, or anything else. A secular ethic doesn’t need any of that. What it needs, but cannot itself provide, is an assurance that life is ultimately worth living, a distinctive version of what Charles Taylor has called “hyper-goods,” a justifying vision of the whole enchilada.

Fleischacker’s book raises deep questions and repays close reading, (we will almost certainly run a full review in a future issue), but one is left wondering whether he has exchanged quibbling about the meaning of God for quibbling about the meaning of Torah. The question of whether, and to what extent, the wisdom—paradoxical or otherwise—of divine teaching ought to affect the way of the world abides.

Suggested Reading

“I Am Talking to You Like King Solomon”

Saul Bellow once called Nabokov a “cold narcissist.” His letters to his wife, Véra, decisively dispel that common misconception.

Saladin, a Knight, and a Jew Walk Onto a Stage

Outside of Germany, Nathan the Wise is one of those works more often read than performed, and more often read about than actually read.

Smitten with Sympathy

As the sea split, God shushed the angels, saying, “My handiwork is drowning in the sea and you are reciting songs before me?”

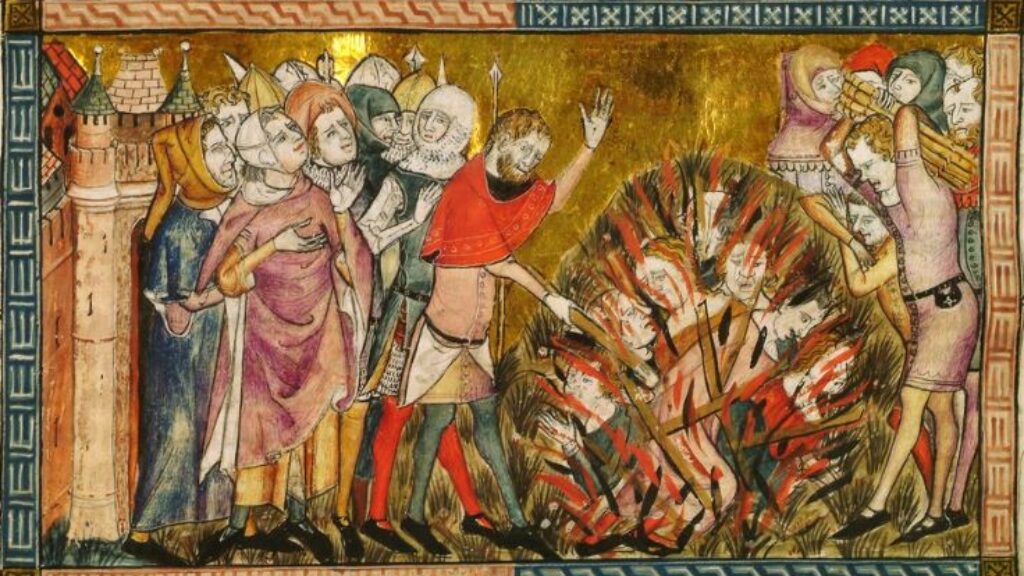

Jews, Genes, and the Black Death

This is the version of history that many of us heard in Hebrew school: Jews were saved from the plague by handwashing, kashrut, and burying their dead quickly.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In