Letters, Fall 2016

Frozen DNA

Rabbi Shlomo Riskin’s review of Jonathan Sacks’s latest book, Not in God’s Name: Confronting Religious Violence (“Religion and Power,” Summer 2016), points to some problems in Sacks’s eloquent exposition. I find other troubling arguments.

Rabbi Sacks begins by bluntly facing the facts of Abrahamic religions’ complicity in violence over the centuries. His exculpatory argument, based on nuanced exegesis, is similar to that of other defenders of religion: The evildoers and the blamers of religion have selectively misread the texts. What holy texts (properly understood) call on us to do is to be benign and peace-loving.

By continuing to sanction the texts as revealed and holy, any religious interpreter or cleric, no matter how well-meaning, reinforces the authority and sacredness of the text as a whole, leaving the door open to those championing the sacredness of the violence-condoning passages. Sacks captures the difficulty: violence-condoning passages (in Judaism and Christianity), now mostly inactive, remain “dormant like frozen DNA,” available for revival to justify evildoing. The argument based on reaffirming scriptural authority is self-defeating; it keeps this DNA alive in the realm of revealed truth.

In addition, in his stirring conclusion, Rabbi Sacks summarizes the “absolute values that make Abrahamic monotheism the humanizing force it has been at its best.” He lists the sanctity of life, the dignity of the individual, moral responsibility of the rich for the poor, the need to resolve conflicts peacefully, and so on. These are the same values advanced by secular humanism; but humanism does not have to explain a historical legacy of purportedly divine sanction of all the opposite.

Some 45 percent of the world’s population is non-Abrahamic. Their major traditions do not see humanity as consisting, theologically, of Us versus Them. Any rethinking of the role of religion in human violence should take this into account.

Robert J. Muscat

Sarasota, FL

Rabbi Sacks’s response to our review can be found here, followed by Rabbi Riskin’s rejoinder.

Brandeis‘s Puritan Sabbaths

David D. Dalin’s rather adulatory review of Jeffrey Rosen’s new book about Louis D. Brandeis (“Old Isaiah,” Summer 2016) requires some qualifications. A most problematic aspect is the author’s claim that from 1905 to 1910 Brandeis was “a committed assimilationist” and thus ignores his Jewish development during those years; consequently, he also partly errs in judging the nature of his Zionism. With all due respect, as my Brandeis of Boston expounds, Brandeis was never a full assimilationist; at the very least, he consistently paid meaningful dues to the local Jewish pre-federation organization. As delineated in my article “The Enigma of Louis Brandeis’s ‘Zionization’: His First Public Jewish Address” (American Public Life and the Historical Imagination), he tried to mobilize the local Jewish vote on behalf of the Protestant candidates who ran for the mayoralty of Boston, a city he deeply cherished. In this endeavor he looked to advance values such as good citizenship, public and personal decency, “cleanliness” (Brandeis’s pertinent self-coined terminology), work ethic, and commitment to quality education. The local Jewish community’s positive response to Brandeis’s appeal was a major factor that gradually remolded Brandeis to actively identify with his own ethnic group.

This early political biography of Brandeis proved to be important. Brandeis’s famous rift with Chaim Weizmann was essentially driven by his loyalty to these Puritan-like values. Similarly, Brandeis identified with the HaShomer HaTza’ir kibbutz movement, not because it was leftist, not to mention its pro-Soviet tendency, but because he believed then that it was most faithful to the civic values the Yishuv crucially needed on its way to building a state. Brandeis’s fast alliance with David Ben-Gurion was another instructive aspect of this course of this genuine American-Jewish Zionist.

After he quit the Supreme Court, Brandeis further studied and came to embrace the legacy of the great Jewish prophets, among them Isaiah. All this is not to say that social justice was marginal for him; rather, the full picture of his life and the balance of his legacy should always take into account his commitment to a Western civic culture at whose center were public-republican values and personal virtues. His well-known social-liberal course and enlightened jurisprudence should not overshadow his deeply rooted, ever-relevant republican elements.

Allon Gal

Professor emeritus Ben-Gurion University of the Negev

via email

I was astounded to read a scholarly article about Brandeis’s Jewishness that omits facts that would require a psychological analysis of why Brandeis wasn’t more “Jewish” than he was. Brandeis had a very close relationship with his mother’s brother Lewis Naphtali Dembitz and changed his middle name from David to Dembitz. Dembitz was a founder of the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations. He also wrote a classic book Jewish Services in Synagogue and Home, where he displayed great erudition in Talmud, codes, and many disciplines. Brandeis describes his uncle’s behavior on the Sabbath, where he prayed and studied Torah all day, and how it was an other-worldly experience. It is difficult to understand how Brandeis was not influenced to become more observant due to his attachment to his beloved uncle.

Eliyahu Cohen

David G. Dalin Responds

While I’ve always admired Allon Gal’s writings about Brandeis, I must question his suggestion that Brandeis’s “First Public Jewish Address,” proves that he was not an assimilationist. Indeed, in this November 1905 address, as Allon himself writes in his 1980 book Brandeis of Boston, Brandeis affirmed that “There is no place for what President Roosevelt has called hyphenated Americans. There is room here for men of any race, of any creed, of any condition in life, but not for Protestant-Americans, or Catholic-Americans, or Jewish-Americans.” Customs that tend to perpetuate differences in origin or religious beliefs, Gal quotes Brandeis as saying, “are inconsistent with the American ideal of brotherhood, and are disloyal.” Moreover, Brandeis was very close to his brother-in-law Felix Adler, who had renounced Judaism to become the founder of the Ethical Culture Movement. Before he emerged as a leader of the Zionist movement, Brandeis was so far removed from Jewish life that, as Melvin Urofsky has noted, when his name was proposed for membership in the newly created American Jewish Committee in 1906, he was rejected because “he has not identified himself with Jewish affairs, and is rather inclined to side with the Ethical Culturists.”

As to Eliyahu Cohen’s question about the influence of Brandeis’s beloved uncle, Lewis Naphtali Dembitz, a meticulously observant Orthodox Jew and Jewish scholar: While Brandeis would later nostalgically recall the traditional Jewish Sabbaths and rituals that he experienced in his uncle Lewis’s home, his great admiration for his uncle never influenced him to observe the Jewish Sabbath or to emulate his uncle’s commitment to Jewish prayer and ritual in his own home. Rather, when the young Brandeis changed his middle name from David to Dembitz in honor of his uncle and, inspired by him, pursued a career in the law, he was emulating Lewis Dembitz, the prominent Louisville lawyer, rather than Dembitz the Orthodox Jew. Brandeis’s secular religious behavior and orientation owed more to the influence of his mother Frederika, who “was adverse to religious enthusiasm of any sort and raised her children to cherish the ethical teachings of all religions and the rituals of none.”

Free the Rapoport Mermaids

I wish to thank you for publishing Allan Nadler’s review of Marc B. Shapiro’s groundbreaking work on the large-scale censorship and editing of history practiced by the haredim (“Pious Censorship,” Summer 2016). It was quite a surprise to see our own Rapoport family crest pop up, where the topless mermaids were transformed into Orthodox, but still topless, mermen with kippot and pe’ot. Such outrages will not stand.

Benjamin Bilski

via email

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

What a Friend We Have in Jesus

A new crop of books about Jesus, by Jews and for Jews.

Palestine Portrayed

The 1948 War and the problems it left unresolved have returned to the top of the agenda for both diplomats and historians.

North Africa during World War II

Mentions of wartime North Africa conjures up visions of Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, and Claude Rains in Casablanca. It was far worse than that...

Jews Not without Money

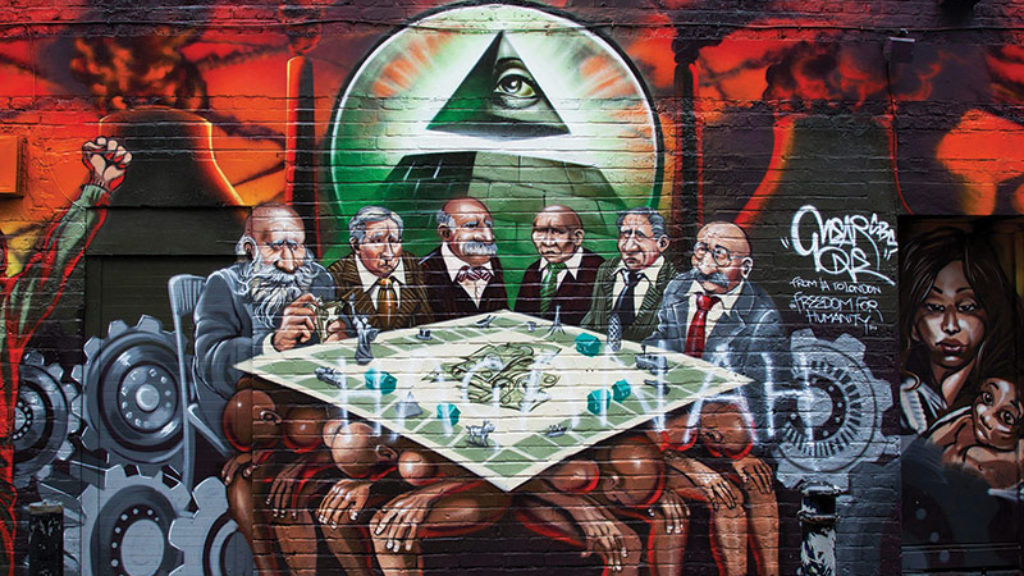

Jews, Money, Myth, at London's Jewish Museum, normalizes the Jewish relationship with money without negating those factors that made this particular historical association especially fraught.

E. Randol Schoenberg

On Brandeis' Jewish background, please see my recent article on his genealogy at http://www.avotaynuonline.com/2016/05/4446/