The Last Bedtime Story: Roz Chast’s Sort-of Tour Guide

Over the past four decades, the cartoonist Roz Chast has become a fixture at the New Yorker, which has published nearly a thousand of her slice-of-life meditations. They swerve from memoir to satire or social commentary, and occasionally to something like philosophy. Her recurring themes include relationships, midlife/post-midlife crises, mom brain, and New York urban living. Among her characteristic captions are “The Gingerbread Man Hits 50,” “Urban Trail Mix”—the accompanying drawing is a bag full of anxiety meds—and “Orpheus Descends into the Laundry Room.”

That last cartoon is emblematic of Chast’s work, blending high and low, the casual with the sublime, the eternal with the ephemeral. Even her earliest cartoons for the New Yorker (she’s been appearing in its pages since 1978) and other outlets are marked with a sort of resigned wisdom. There’s often a heady, cerebral anxiety running through the background of her work, but in the forefront there is rarely anything but warmth. Her subjects, even the wacky ones and the lonely ones and the sad ones, are depicted kindly and with empathy.

She’s also, to be honest, not very funny—not in a conventional way, anyway. Her comics aren’t laugh-out-loud funny and they’re not chuckle-to-yourself funny. Rather, one looks at Chast’s wavering lines and the wry text of her cartoons and slowly realizes the perfect aptness and humor of her observations. And one feels that one knows her.

Her new book, Going into Town: A Love Letter to New York, begins with an anecdote that doubles as a curious confession: Chast and her family successfully fled the city 27 years ago for the (relative) affordability of suburbia. In the book’s early pages she describes the move as bewildering: A panel depicts her two-year-old son toddling down a street lined with multicolored, empty crack vials, saying “I eat dat.” Four pages later, we find Chast looking perplexed in front of a big oak, thinking: “I own this tree.” Flash forward and the author’s daughter is going away to college in New York. That’s where we begin the story of the book itself, its reason for existing. Realizing that her daughter knows nothing of the urban wilderness her mother once inhabited, the elder Chast takes it upon herself to bequeath her accumulated wisdom in the method most natural to her, a comic book: Nina’s Basic NYC Book: Focusing on the Borough of Manhattan, upon which this book is based.

It is a charming book, and a surprisingly personal one, as if Chast needs to tell her daughter one last favorite story before she leaves home. She paints the city as a very private, very personal playground where she spent the most significant years of her life. Her career has been spent crafting loving portrayals of its inhabitants and their neuroses, and suddenly her daughter has announced her intention to have her own relationship with the city, to lay claim to it on her own terms.

Chast’s book, like the city, is fast but full of surprises, and stumbling across each one is a small joy. Even while giving over a lesson as simple as the north-south direction of avenues (as opposed to streets), there’s something charming and compelling about her sloppy, dramatically not-to-scale maps.

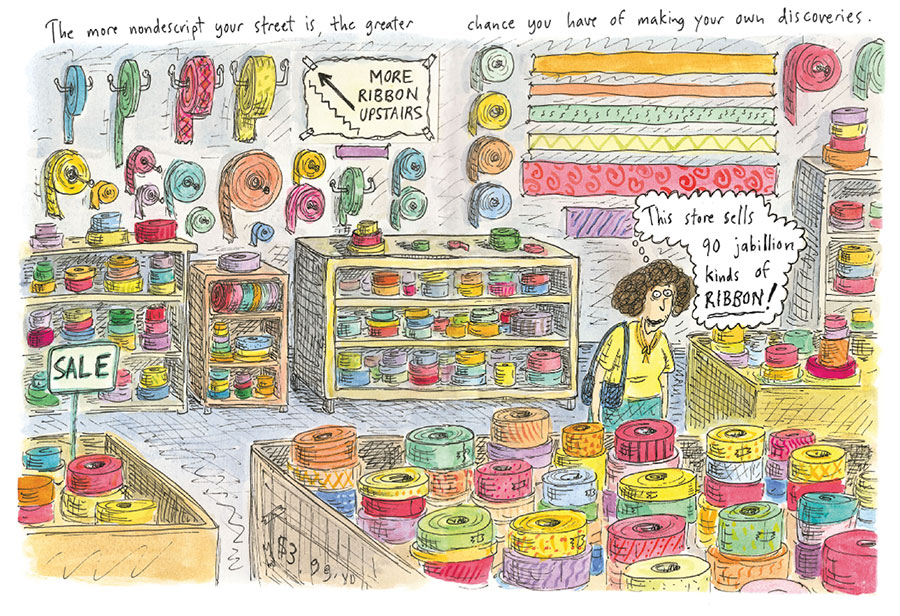

Upon turning to a two-page splash of cartoon-Chast entering a shop that sells only ribbon, I inadvertently uttered an audible cry of delight while on the B train traversing the Manhattan Bridge—I’ve been to that shop!—causing, of course, my fellow straphangers to glare in silent disapproval and wonder whether I was insane or merely a tourist who had just realized I could see the Statue of Liberty from there.

This book then is an impassioned, revealing parental monologue of the sort that is both necessary and almost inevitably ignored, the ephemeral prayers we say as our children slip off to sleep or out of the house.

Chast is a product of New York—not Manhattan but Brooklyn, its bigger and dirtier misshapen kid sister. Nowadays it is glamorous, but in Chast’s childhood it was the cheaper, crappier version of the Lower East Side, where Jews like those of her parents’ and grandparents’ generations moved to live modest lower-middle-class lives.

Throughout the book, Chast interjects bits of her own parents’ ambivalent relationship with Manhattan. They boarded the subway and made the cross-borough voyage only occasionally and only to see a Broadway show, never stopping in a restaurant, never lingering. “My mother blamed her bad feet,” she writes, “but I suspect there were other concerns.” A cacophony of word bubbles follows: Pickpockets! Dirty! Too expensive! Crowded! Mrs. Zimmerman ate at one of those restaurants* and she found a cockroach in her lasagna! (The asterisk leads us to this text: “i.e., any place in Manhattan.”) Elsewhere in the book, Chast tells us that whenever her father went into Manhattan he brought his own food with him: a piece of honey cake wrapped in wax paper or graham crackers in a bag. And yet, she writes, the city is a paradise of food: “If you can’t find what you want to eat here, maybe you don’t like food.”

In such vignettes, Chast’s parents come off as small-minded, xenophobic, and poor. It’s not that she’s belittling them, but there is an underlying feeling: Thank God I escaped that, and I can give my daughter something better. In the book’s first pages, Chast tells us that when her family decided to leave Manhattan their choice was either the suburbs or Brooklyn, near her parents. “For some people, this would have been a plus,” she writes, “but I had ‘mixed feelings.’” What follows is an explosion of NOs scribbled all over the page.

Chast gets much of Manhattan spot-on. Practically the only thing she doesn’t talk about is money. Life in Manhattan is hard to achieve, she admits, but it has always been hard. The “Stuff to Do” chapter features a lot of free museums and activities, but it paints thriftiness as a fun leisure-time activity rather than a legitimate question of survival in this city where a restaurant bill might be more than you earn in a day. Her Manhattan is a wonderful, cacophonous collection of cultures, a kind of amusement park. There is an almost willful refusal in this book to admit the endangered quality of the spots and people Chast treasures. The city is thriving, as it was not when Chast fled its crack vial–infested streets, but these days there are a lot fewer of her beloved “Stores of Mystery,” and a lot more unpopulated Chase ATM walk-in kiosks.

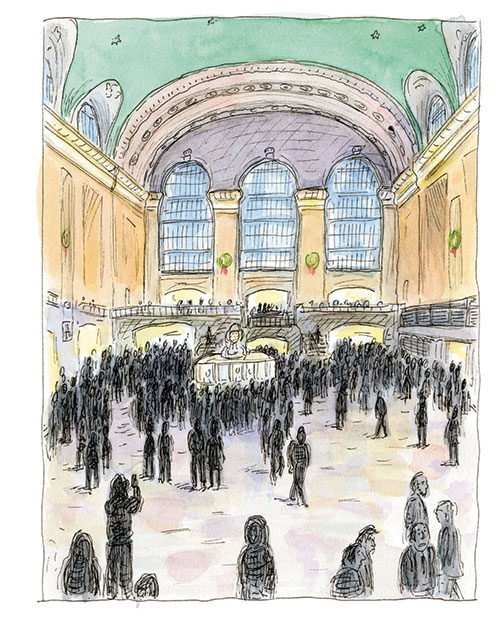

As a fantastically successful cartoonist for the New Yorker, Chast is an example of a certain kind of Manhattan fairy tale come true, and the charming, buoyant optimism that runs through this book is one way she acknowledges this. When she comes to Grand Central Terminal, she describes the lovingly restored astrological murals that adorn its ceiling. The terminal narrowly avoided being replaced with a squat, ugly box building, but the murals remind us, Chast says, that “sometimes, the good guys win.”

In the book’s later chapters, Chast discusses the nitty-gritty of Manhattan living. She tells her daughter about crosstown subway navigation, all-night diners, window shopping, and museums. She provides a list of her five favorite parks—all text, no illustration—including favorite little details, while leaving it to the reader to discover how big or small they are, how dangerous or inviting.

Chast’s illustrations disappear all but entirely in the book’s final pages, when she turns to E. B. White’s 1949 guidebook Here Is New York for a couple of meaty, meaningful quotes. White’s book came out in the years after World War II, at the beginning of the baby boom, when refugees from Europe emptied into America, when a whole new surge of non-native New Yorkers would claim the city for their own reasons. In an eerily prescient paragraph, White wrote:

The city, for the first time in its long history, is destructible. A single flight of planes . . . can quickly end this island fantasy, burn the towers, crumble the bridges, turn the underground passages into lethal chambers, cremate the millions. . . . All dwellers in cities must live with the stubborn fact of annihilation . . . [but] New York has a certain clear priority. In the mind of whatever perverted dreamer might loose the lightning, New York must hold a steady, irresistible charm.

To which Chast adds, in her own voice:

But New York came back. This is the best place in the world, an experiment, a melting pot, a fight to the death, an opera, a musical comedy, a tragedy, none of the above, all of the above. We’re a target for seekers and dreamers and also nuts. We live here anyway.

Maybe she’s right that New York is an indestructible phoenix. Going into Town, which began as a “sort-of guide” for her daughter and became “a thank-you letter and a love letter to my hometown and New Yorkers everywhere,” ends with a grainy snapshot of Chast and her mother bundled up for winter, standing in front of a subway station.

Suggested Reading

Ready to Wear

Textiles can tell the story of how modernity, for all its many blessings, often erases the practices and values of the collective, celebrating the individual at the expense of community and novelty or fashion at the expense of tradition.

Prague Summer: The Altneuschul, Pan Am, and Herbert Marcuse

A mysterious memoir of planes, Marx, and minyans.

Exodus and Consciousness

Who left Egypt ? And how did the Israelites experience God? Richard Friedman is a biblical detective, James Kugel is more of a literary anthropologist.

Two Poems

Two untitled poems by Avraham Halfi, translated by Leon Wieseltier.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In