Tattooing God’s Name, a Jewish Adventure Out West, and Ultra-Orthodox Voting Patterns

Although scholarly articles can be dense and difficult to access, fascinating new things are constantly being published in academic journals of Jewish Studies. Here’s a quick round-up of three interesting essays from leading journals, Review of Rabbinic Judaism, American Jewish History, and Jewish Social Studies.

Tattooing God’s Name

Most people know that the Bible (Lev. 19:28) forbids tattooing. This idea is so strongly embedded in Jewish culture that there is a persistent myth that tattooed Jews may not be buried in a Jewish cemetery. However, Meir Bar-Ilan (of Bar-Ilan University) has recently argued that many Jews likely did tattoo themselves in antiquity—with God’s name, no less (“Body Marks in Jewish Sources: From Biblical to Post-Talmudic Times”). The divine name was thought to afford the bearer a measure of protection. One thinks, here, of the mark of Cain (Gen. 4:15), set by God to protect the murderous brother from vengeance. One thinks, too, of the righteous people of Ezekiel 9:4–6 who were also marked for survival with the divine name.

Bar-Ilan argues that the Israelite practice of tattooing God’s name also been hiding in plain sight, in one of the most recognizable Biblical texts, the priestly blessing (Num. 6:22–27). In Bar-Ilan’s translation:

“The Lord bless thee, and keep thee; The Lord make His face to shine upon thee, and be gracious unto thee; The Lord lift up His countenance upon thee, and give thee peace.”

So shall they [the priests] put my Name upon the children of Israel, and I shall bless them.

Usually, the idea of the priests “putting” God’s name on Israel has been understood metaphorically, as a consequence of the priestly blessing itself. (The standard Jewish Publication Society translation of verse 27 reads “Thus shall they link My name with the people of Israel.”) Bar-Ilan argues, however, that the priests literally put God’s name on the children of Israel by inscribing it on their flesh. This may also be the original idea in the texts that give rise to the practice of tefillin, including Exodus 13:9: “And this shall serve you as a sign on your hand and as a reminder on your forehead.”

Bar-Ilan’s insight allows him to offer a fresh reading of the third commandment, not to take the Lord’s name in vain. Normally, this difficult text is interpreted (in both classical rabbinic commentaries and contemporary scholarly literature) as a prohibition against swearing falsely in God’s name. But this makes it troublingly similar to another one of the 10 commandments: not to bear false witness. Bar-Ilan suggests a better understanding of “don’t take the Lord’s name in vain” is that someone who has God’s name on his body should avoid bad behavior, lest he desecrate that name.

Beyond the Bible, Talmud Yoma 88a admonishes those inscribed with the divine name to avoid bathing so as not to wash away the sacred mark, though this does suggest a less permanent form of writing. The ancient and esoteric mystical Hekhalot literature, in turn, describes humans inscribing themselves with multiple complex and secret divine names for protection; there are even descriptions of God inscribing himself with his own name. The latest example that Bar-Ilan cites, Sefer Yohasin (Southern Italy, 1054 C.E.), tells of a certain Rabbi Ahima’az, who resurrected a dead person by writing the divine name on the arm of the corpse.

What, then, of the prohibition in Leviticus 19:28? In light of Bar-Ilan’s argument, should we still read it as a prohibition against tattooing? Bar-Ilan doesn’t say. It seems to me, however, that it would be helpful to draw a distinction between permanent tattoos and impermanent writing on the body. Most of the texts he marshals in support of his theory of widespread tattooing could instead be read as evidence that people simply wrote the divine name on the surface of their skin, which wouldn’t violate the prohibition against permanent, subcutaneous alteration in Leviticus 19:28.

Bar-Ilan offers a volley of speculative theories as to why Jews stopped writing God’s name on their bodies. Perhaps the most convincing one is that the practice waned as Jews grew increasingly reluctant to write or pronounce the divine name in any context.

Modesty in the Face of Majesty

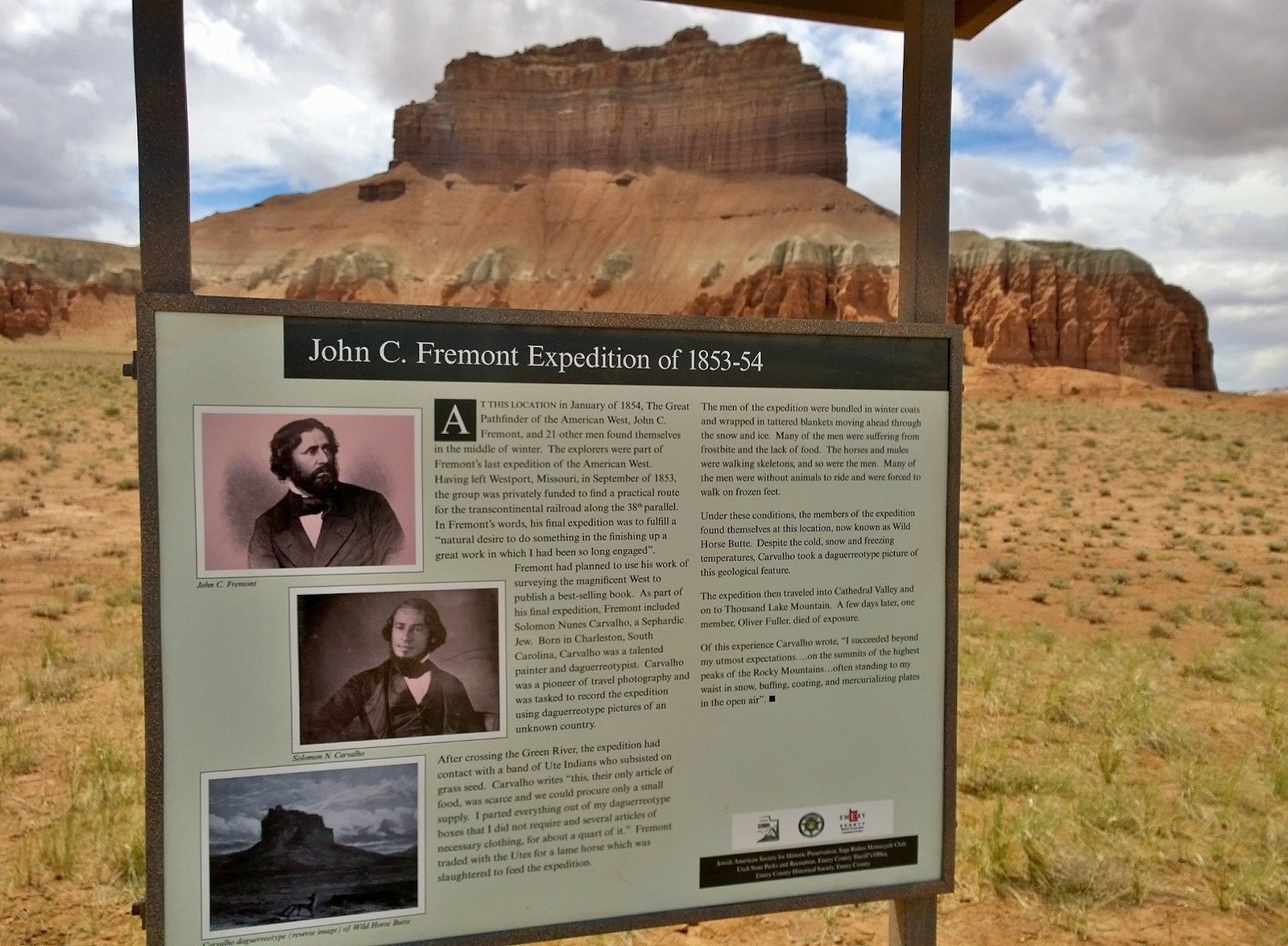

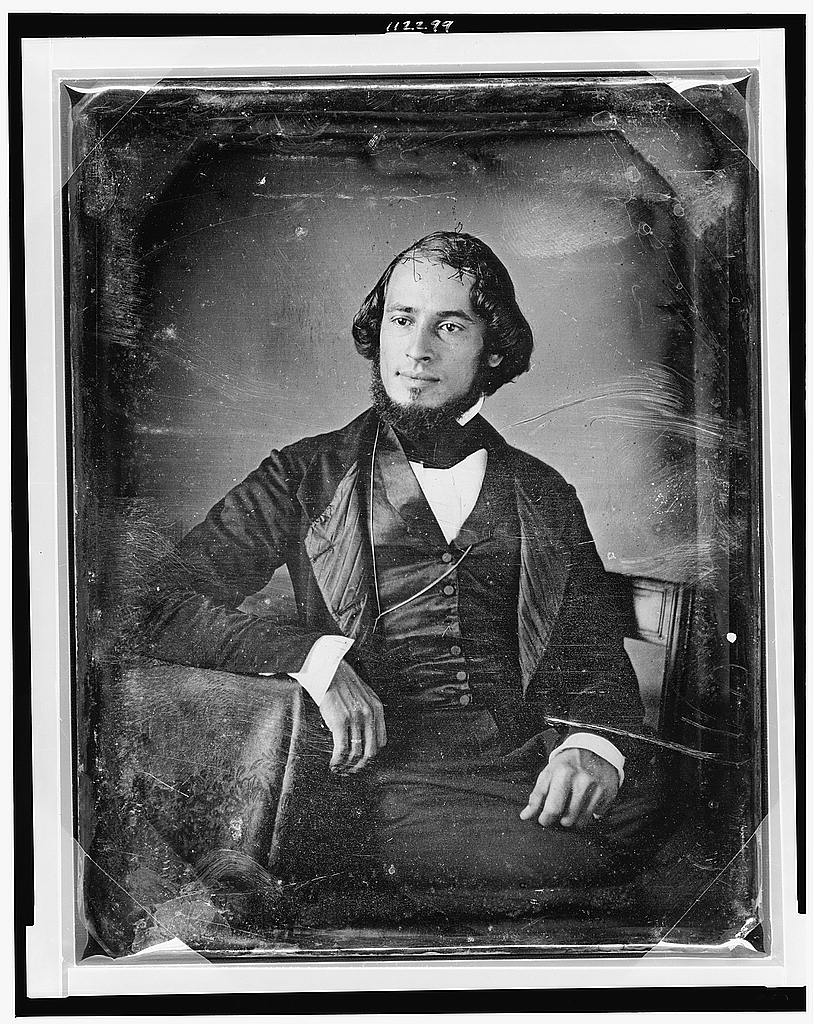

In the early 1850s, the young, successful portrait photographer and first-generation American Jew Solomon Nunes Carvalho was asked to join John C. Fremont’s fifth westward expedition. Fremont wanted to chart a course for the intercontinental railroad; he wanted Carvalho to take the pictures. Carvalho said “yes” even though he had never ridden a horse.

Despite freezing weather that interfered with the chemical process of creating daguerreotypes, and other dangers that routinely put him in mortal danger, Carvalho took many photographs of the expedition’s members and the jaw-dropping landscape. He also wrote regular letters home to his wife which he later crafted into a colorful account of the (ultimately failed) Fremont expedition—the only one ever written—called Incidents of Travel and Adventure in the Far West.

As one might expect from an account crafted from intimate letters, Carvalho’s book is personal, funny, and self-deprecating. He frequently pokes fun at his own unfitness for the rigors of the wilderness. Once, during a group hunt, he recklessly gave chase to a buffalo and shot the animal in panic when it turned and reared up to attack him. In the aftermath, Carvalho realized that he had lost his party. By luck he found them again, and only then did he realize that he had forgotten to bring back the buffalo’s tongue (as was customary) as proof of his conquest.

In “‘To prove the correctness and authenticity of my statements’: Solomon Nunes Carvalho’s Revision of the Western Travel Narrative,” Fitchburg State University professor Michael Hoberman explains that popular authors of the time such as Mark Twain and Harriet Beecher Stowe, “were expected to furnish hyperbolic descriptions of an untamed, untamable landscape that was not only oblivious to human history but also openly contemptuous of it.” Explorer-heroes, whether real or fictional (from Davy Crockett to Natty Bumppo) were larger-than-life. By contrast, Nunes gently mocked his own inadequacy in the wilderness and repeatedly emphasized communal moments and the care he received from (and, in some cases, ministered to) his fellow expedition members, Native Americans he met along the way, and Mormons in Utah who took him in when he was too ill to continue on the expedition. Hoberman suggests that Carvalho’s perspective reflected the Jewish diasporic experience: Jews tend to hold fast to their community—wherever that may be.

(For more on Solomon Nunes Carvalho and Jewish contributions to early American culture, see Esther Schor’s review of the exhibit By Dawn’s Early Light.)

Red hat, black hat

Forty-five years ago, Milton Himmelfarb famously observed that Jews earn like Episcopalians and vote like Puerto Ricans. But this did not then, nor does it now, apply to haredi Jews. In “‘Borough Park was a Red State’: Trump and the Haredi Vote,” Nathaniel Deutsch (director of the Center for Jewish Studies at University of California, Santa Cruz) asks two questions: How did haredim vote in the 2016 presidential election and why? The answer to both, not surprisingly, is complex.

On the whole, haredi voters supported Trump, though voting patterns varied significantly, even wildly, from one ultra-Orthodox community to the next. Lubavitchers were strongest in their support of Trump, whose daughter Ivanka made a much-publicized visit to the grave of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson during the campaign. In New Square (Rockland County, New York), Skverer leaders encouraged their followers to vote for Hillary Clinton and she received 96 percent of the haredi vote—a number that Deutsch suspects came from a sense of hakaras ha-tov (gratitude) that the community felt for former President Bill Clinton’s decision to commute the sentences of four imprisoned Hasidim from New Square. In the Satmar communities of Kiryas Joel and Williamsburg, leaders endorsed Clinton, but the vote was fairly evenly split between the candidates, probably because of the current struggle for leadership in those communities. On balance, though, American haredim supported Trump.

Why the strong support for Trump among ultra-Orthodox Jews? Deutsch suspects a combination of factors. Although in theory many haredim do not support Zionism, in practice many do support the State of Israel and “now hold political views in line with Israel’s current right-wing government and its conservative American supporters.” Conservative social values also play a role, as does strong haredi support for school vouchers. Deutsch also speculates that Clinton’s gender worked against her among haredi voters. As for the fact that the Trump campaign was supported by, Deutch in the minds of many haredim, by the fact that Jared and Ivanka Kushner, and their children, are Jewish.

Suggested Reading

An Entrepreneurial American

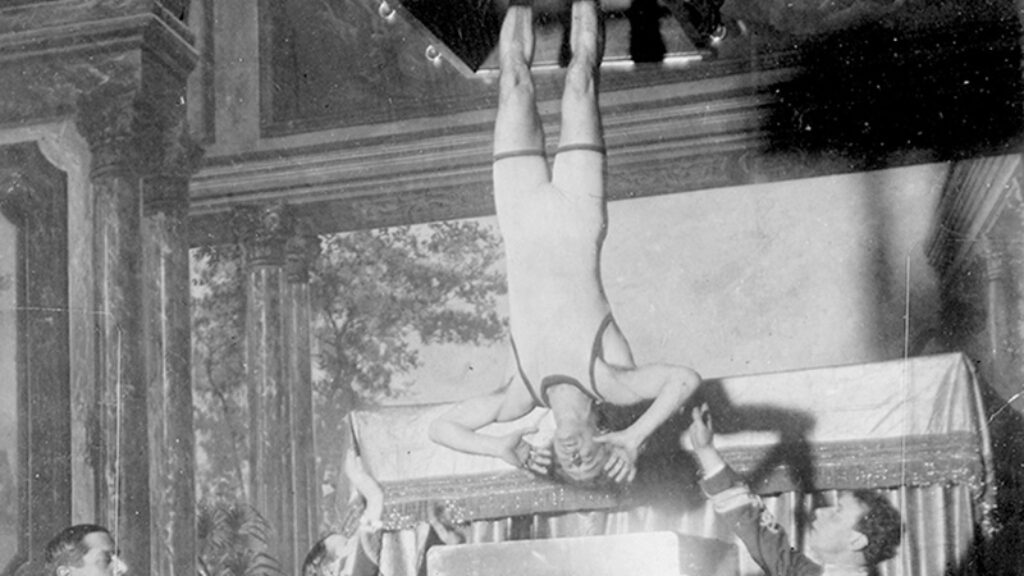

“Houdini created his illusions and handed them down to his brother Hardeen, Hardeen sold them to the Amazing Dunninger, and Dunninger sold them to—my father,” writes Jerry Muller in his review of Adam Begley’s new biography of the great Jewish escape artist.

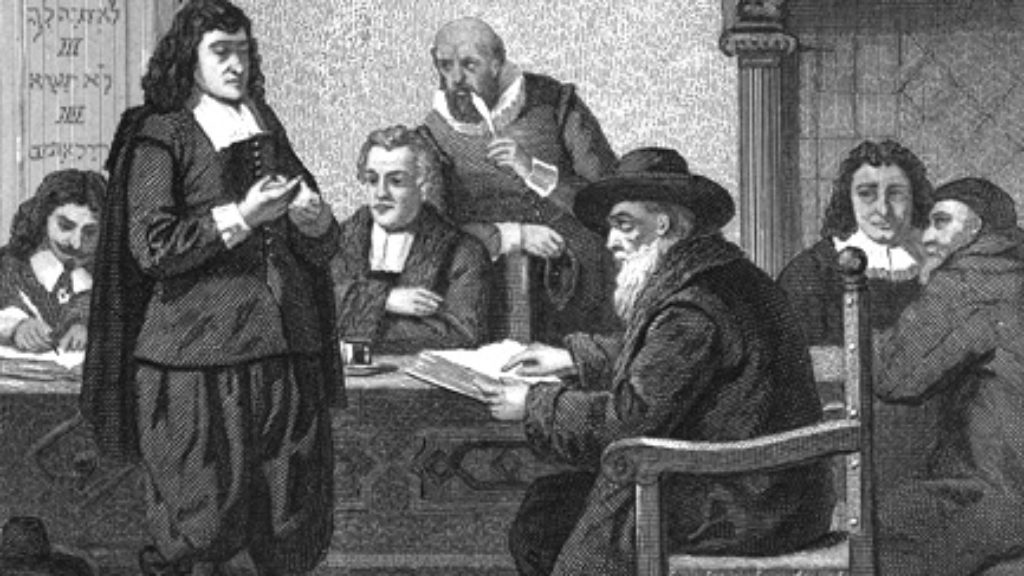

Secularism and Sabbateans

How did the Jews become modern? Three new books trace the roots of Jewish secularization.

Time Ticks Away in Portugal

Tens of thousands of Jews made their way into Portugal in waves between the fall of France in 1940 and the end of World War II. The ordeals Marion Kaplan depicts were not terribly long, but to the people who endured them, they often seemed endless.

A Heretic in the Truth

A new book points out just how elusive Spinoza's ideas on politics were and raises serious questions about his "secularism."

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In