Orpheus on the Lower East Side

Literary history is full of underdogs: autodidacts sprung from unpromising soil, creative lives cut short yet heroically compressed. Even so, the case of the poet and artist Samuel Bernard Greenberg is extreme and probably unique. Born in Vienna in 1893, the sixth of eight children, Greenberg emigrated to New York at the turn of the century with his Yiddish-speaking family to settle on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. At 13, he dropped out of school to work in a leather shop. At 18, he was diagnosed with tuberculosis; he died five years later at the age of 23. His circumstances may bring to mind those of another Jewish poet-painter, Isaac Rosenberg. Raised in poverty on the East End of London, Rosenberg enlisted in the British Army and died in action in 1918—a year after Greenberg—at the age of 27. But Rosenberg’s war poems are highly polished, fully realized works of literary art. They do not reveal the limitations of his formal education any more than Keats’s Odes reveal his class origins. Editors are not inclined to correct them, and poets are not tempted to rewrite them. The same cannot be said of Greenberg’s work. Even his admirers have felt the need to make allowances.

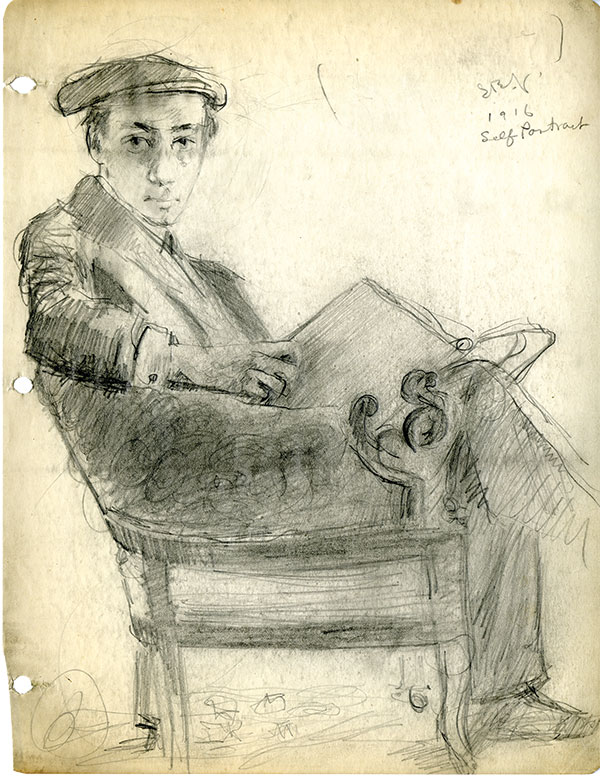

One of the earliest and most ardent of Greenberg’s admirers was another poet who died tragically young, Hart Crane. (Crane took his own life in 1932, at the age of 32, throwing himself overboard from a steamship in the Gulf of Mexico.) Crane’s name will forever be linked to Greenberg’s by a brilliant act of plagiarism, for the story of Greenberg’s posthumous manuscripts is almost as remarkable as the poetry itself. Six years after Greenberg’s death, Crane was shown Greenberg’s handwritten poems by a neighbor in Woodstock, William Fisher, a former curator for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where Greenberg sometimes went to sketch. Fisher had taken an interest in the young poet, giving him books of Emerson, Shelley, Keats, and Browning, and, after his death, taking possession of some of his notebooks for safekeeping and possible publication.

Crane spent several nights excitedly reciting Greenberg’s poems with Fisher and typing up copies of his favorites for personal use. In a letter written at the time, he described Greenberg’s poems as “hobbling but really gorgeous attempts . . . made without any education . . . No grammar, nor spelling, and scarcely any form, but a quality that is unspeakably eerie and the most convincing gusto.” Greenberg was a “Rimbaud in embryo.” Cutting and pasting from a handful of Greenberg originals, Crane assembled a polished mosaic—“Emblems of Conduct”—and published it under his own name in his first book of poems, White Buildings (1926):

By a peninsula the wanderer sat and sketched

The uneven valley graves. While the apostle gave

Alms to the meek the volcano burst

With sulfur and aureate rocks . . .

For joy rides in stupendous coverings

Luring the living into spiritual gates.

Orators follow the universe

And radio the complete laws to the people.

The apostle conveys thought through discipline.

Bowls and cups fill historians with adorations,—

Dull lips commemorating spiritual gates.

The wanderer later chose this spot of rest

Where marble clouds support the sea

And where was finally borne a chosen hero.

By that time summer and smoke were past.

Dolphins still played, arching the horizons,

But only to build memories of spiritual gates.

In Crane’s pageant of “emblems”—mostly cut from Greenberg’s cloth—the wandering artist, the religious apostle, the orator, and the historian-archeologist represent, broadcast, commemorate, or are otherwise inspired by a transcendent spiritual reality that nonetheless remains aloof. Everything in the world of the poem points beyond itself, whether luring the living toward explosive joy or ascetic discipline. Even the dolphins (in one of two lines belonging wholly to Crane) playfully leap over the surface of the sea, “arching the horizon.” But horizons are forever receding, and the poem’s structure is likewise recursive, as if hermetically sealed by its thrice-repeated refrain of “spiritual gates.” That spiritual gates are everywhere apparent, and yet inaccessible, would seem to be one implication of this well-wrought, doubly authored poem.

One can take Crane to task for not acknowledging his debt, as Garrett Caples does in his preface to the expanded reissue of James Laughlin’s 1939 edition of Poems from the Greenberg Manuscripts. One can also wonder at the phenomenon of one poet capable of absorbing so much of the language of another poet without losing his own voice. For Crane did more than leave a paper trail to Greenberg’s manuscripts. “Emblems of Conduct” is the most perfect poem that Samuel Greenberg (mostly) wrote, and yet it easily passes for Crane. Most crucially, by aggressively editing and reorganizing passages of Greenberg’s poem, Crane sustained and clarified Greenberg’s genius, which is fully realized in Greenberg’s work only in parts and is often obscured by a combustible mix of bad spelling, portmanteau words, and ambiguous grammar and syntax. (“My vocabulary has a great memory for foolish bliss,” Greenberg wrote, “rather poor in careful selection and of grammatic assistance unguided.”)

Turning to Greenberg’s “Conduct,” the poem from which Crane most heavily poached, is a revelation both of what was gained and lost in Crane’s patchwork:

By a peninsula, the painter sat and

Sketched the uneven vally groves

The apostle gave alms to the

Meek, the volcano burst

In fusive sulphor and hurled

Rocks and ore into the air,

Heaven’s sudden change at

The drawing tempestious

Darkening shade of Dense clouded Hues

The wanderer soon chose

His spot of rest, they bore the

Chosen hero upon their shoulders

Whom they strangely admired—as,

The Beach tide Summer of people desired.

In point of fact, Greenberg ends “Conduct” with a comma, not a period, and misspells “volcano” (“valcano”), irregularities that Laughlin corrects while leaving others intact. (Later editors would be far more intrusive in their efforts to make Greenberg presentable.) Lapses in literacy and idiosyncrasies of style notwithstanding, “Conduct” is marvelously artful. What it lacks in virtuosity and polish, it makes up for in its haunting final turn, which Crane left on the cutting-room floor. Greenberg’s “chosen hero” is borne on the shoulders of his devotees like a prize athlete or a dying patient. Is he the apostle, the wanderer, or the painter whose tempestuous sketch ignites earth and sky? Most suggestively, he is “strangely admired,” as Greenberg was said to have been by his brothers and their acquaintances. Greenberg’s “sonnet,” as he called it, pivots on the grammatically ambiguous “as,” which hovers between “while” and “in the manner of.” Either way, the hero’s homecoming dissolves into the larger movements of “Beach tide Summer” and “desire.” Why do the people “strangely” admire the hero? Greenberg suggests a quality of obtuseness in their esteem. Their hero is chosen, but their attention seems to dissipate even as it comes to a head. A “Beach tide Summer of people” are at best fair-weather friends. The effect of the last line is like that of a wave washing over a name written in sand. Our hero is fêted and forgotten almost in the

same breath.

No single explanation will account for all of Greenberg’s irregularities. Crane’s first biographer, Philip Horton, who discovered copies of Greenberg’s poems in the famous poet’s posthumous papers (and connected the dots in a 1936 article in The Southern Review), shared his “successive impressions” that the unknown author was “mad, illiterate, esoteric, or simply drunk.” “And yet flash out,” Horton added, “lines of pure poetry, powerful, illuminating, and original, lines unlike any others in English literature, except Blake perhaps.” Horton concluded that Greenberg was a “visionary,” a “Gottbetrunkener Mensch” (no doubt alluding to Novalis’s characterization of Spinoza).

As a descriptive term, “God-intoxicated” has limited explanatory power, but Horton was correct to suggest that Greenberg is in some sense a religious poet. It might be less misleading to say that poetry is his religion. In “Poets,” Greenberg’s poet pounds an anvil at the heart of creation in an effort to emancipate his eternal “essence” from the slavery of time and matter:

He sat as an extricable prisoner bound

To essence, that he sought to emancipate

Kept pounding an envil of generation core

And exchanged his soul a thousand ways

At the rate of centuries unfelt round

As though cloud repeats cloud through days

Or nocturnal heavens beaten lights

That mock the day . . .

Greenberg, with his volumes of Emerson, Shelley, and Keats from Fisher, seems to have combined their influence with elements of esoteric Jewish thought to forge his own spiritual and artistic quest, although it is impossible to say with certainty. In “Man,” Greenberg invokes humanity as the “perfect lay of deity’s crested Herb” and “the winsome weed afloat.” “O love,” he pleadingly asserts a few lines later, in what may plausibly be a reference to Lurianic Kabbalah, “all dieing though everensueing endures / The bitter blinded spark.”

Greenberg frequently gives the impression that he is trying to say everything at once, as if each poem he wrote were his last. “And that which rises from my inner tomb,” he writes in “Words,” “Is but the haste of the starry splendor dome / O thought . . . / O bitter messenger of thousand truths.” But he is not always, and never unremittingly, Sturm und Drang. He can be droll (“Very bad for an ap[ar]t[ment] jew to claim / everlasting renaissance”) or startlingly direct and accessible (“Nurse brings me Medicine! Medicine? / For me! God, 20 years old!”).

His favorite word for what he sought in poetry was “charm,” and perhaps his most pervasive quality is an alluring whimsicality. In “The Birds That Lost Their Trees,” he describes “a tiny cheepy” that “Blossomed gold” over “a river city,” its voice a “pattering of bells” (“Chip tip chip tip”). In the final stanza of “The Pale Impromptu,” Greenberg envisions “the minstrel, bent in leagues of Frozen charm,” yet capable of “Thawing melancholy / Into”:

Early psalms

river rhodes

tale of lamps

Satyres burial

Paradise shrine

Noble realms

Mirrors envil

Clover’s muse

“O soul!” Greenberg concludes, “enlivened from dire perfume.”

Laughlin, a preeminent publisher of modernist writing, speculated that Greenberg had come in contact with contemporary surrealism by 1915 when “The Pale Impromptu” was composed. Commending Laughlin for his prescience, Caples observes that in recent years Greenberg’s work has “largely been championed by surrealist or surrealist-inflected poets.” However, more is likely to be lost than gained by attributing the eccentricities of Greenberg’s writings to his release of the creative potential of the unconscious mind. When family and friends were baffled by his recitation of his poems, Greenberg expressed sincere frustration. They seemed clear enough to him. He knew what he meant to say, even if the effort of saying it stretched his linguistic resources to their limits and beyond, as it often did.

But if Greenberg’s reach exceeded his grasp, it also altered his grip, propelling his work into the experimental climate of early 20th-century literature. His linguistic innovations are often difficult to differentiate from mere mistakes because both stem from the same cause: His time was up almost before he could begin. He responded to this seemingly impossible roadblock with an extravagant self-reliance: He spelled as he pleased and enlarged his vocabulary at will: slepted, balzomized, aptonized, obeyance, stally, irragulate, abcedarian, unmersion, prominento, woob. Greenberg’s inventions may sound Joycean, but Joyce’s wordplayderived from an overabundance of linguistic resources; Greenberg’s was born of deprivation. He needed more words than he knew or had time to learn, and so he invented them. To a remarkable degree, he turned his ignorance into a strength. At very least, he refused to let it get in his way.

Greenberg’s literary status remains uncertain. In 2005, Katalanché Press brought Greenberg back into print for the first time in nearly half a century, albeit in a limited-edition booklet titled Self-Charm: Selected Sonnets and Other Poems. New Direction’s reissue of Poems from the Greenberg Manuscripts is another promising sign. Someday soon, one hopes, a substantial edition of Greenberg will appear with consistent and transparent editorial practices. In the meantime, Poems from the Greenberg Manuscripts is, as Caples puts it, “a reasonable stop-gap, as a way to bring this work before a new generation of readers.”

As stop-gaps go, it has a great deal to recommend it. Laughlin’s volume, with its still-vivid essay and thoughtful selection of 22 of Greenberg’s lyrics, remains a classic, and Caples has supplemented it with 10 more poems and three prose pieces, including “Between Historical Life,” Greenberg’s moving autobiographical narrative. But readers should be warned: The version of “Between Historical Life” reprinted in Poems from the Greenberg Manuscripts has been aggressively corrected for spelling and grammar, and—less forgivably—purged of portmanteau words.

Written in the form of a deathbed letter to his brother Daniel, “Between Historical Life” displays both the sorrows of Greenberg’s life and the peculiar lyricism of his language. “Vienna is a dim symphony,” but he vividly recalls tipping his cap as the carriage of the emperor passed: “[T]he faint smile of the Kaiser Franz Joseph is still clear and distinctly felt by me in this anxious affair of waiting to see him roll by as we deeply hide in gentle honor.” His most cherished early memories are of his brother Daniel, playing piano for guests in a “dingy room” (“Candles and low divans and carpets gave a glow of life and cheer”). His father—a maker of metalwork used for ceremonial purposes and a man “capable of mastering his own independence”—departs for the United States first. The children follow, accompanied by their mother, “the heroine of life’s care and great insight of love to me.” Of his mother’s death, Greenberg, who was 15 at the time, writes:

Our mother gradually became ill, ear-trouble, germ trouble, nose trouble, skull trouble—death trouble resulted and the family buried her somewhere on Long Island, where a cemetery called Washington was the grave for many poor victims, as our unpraised love was settled. We returned to a café near the doom place, where gathered a party of thirty or more, ate cheese and eggs with a schooner of beer and coffee. The rituals of the Jewish religion demand that one remain seated for seven days upon the floor. Well, we sat on soft cushions (the angels of wealth!). Thus ended a sorrowful, meaningless jubilee in an empty, beautiful world, with scarce a flower knowing joy.

“[F]or ten years,” the surviving members of the family live “In the Street of Suffolk, corner of Grand,” where “the poverty and insult of life cannot find sufficient words on paper.” Writing becomes an all-consuming passion: “I wrote anywhere and here, read merely to gain lettered vowels for the sake of rhyme, rewrote books, recited in a furnished room all alone.” But his apprenticeship, begun in haste (“as fast as the life of an epicurean in a tower of scientific perseverance”), is cut short when his tuberculosis recurs: “[T]he old story of weakness returned. I got back to the hospital of descending charity . . . Where was school? O what I would give for the knowledge of grammatic truth!” (Greenberg actually wrote, “O How I would give for the knowledge of grammatic truth,” which rather brings the point home.)

At the end of his brief life, Greenberg could not have been confident of his chances of literary survival. That some of his best poems so quickly found their way into Crane’s hands, and that Crane was so perfectly equipped to capitalize on their strengths, is almost enough to convince one that, as William Blake insisted, no great work of imagination is ever lost. It is a fate Greenberg could not have foreseen. “Between Historical Life” nonetheless concludes with an expression of gratitude toward his poetry for curing him of his fear of death. “Art has mended my insane danger feelings,” he writes, “owing to the memory of writing things which is not common to thought in real life of action.”

Like any poet, Greenberg wanted to be read and understood, but self-recognition ultimately meant more to him than public recognition. He knew that his poetry was “not common to thought” but rare and remarkable, and that knowledge was all he needed: “I must say I possess the peace and love which robs me from pain and existence.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Days of Redemption

Did early Zionists abandon Messianism or inherit it? Or, as Arieh Saposnik argues, did they do something more subtle and interesting?

Prague Summer: The Altneuschul, Pan Am, and Herbert Marcuse

A mysterious memoir of planes, Marx, and minyans.

Mystical Teachings Do Not Erase Sorrow

In Yehoshua November’s new collection, however, it turns out that the difficulties of being a Jewish poet do not primarily flow from being either Jewish or a poet but from the underlying difficulties of life itself.

The Warning Song and the Medlars: Two Stories

Glikl's account of her life as a wife, mother, and businesswoman was so different from anything known in her 17th-century Jewish world that there wasn't even a word to describe what she was writing. Two stories from Chava Turniansky's definitive new edition.

gershon hepne

GOD INTOXICATED

The man Novalis called a Gottbetrunkener Mensch,

Spinoza, whose first name means “Blessed,” Latinized as “Benedict,”

might not have minded if men called him “Bensch”----

----as in Grace After Meals I----for serving thoughts which philosophic men addict.

He followed Noah who was God-intoxicated, we're told in a myth,

unlike Baruch Spinoza misunderstood by just two-thirds of his kith.