Setting the Table

The title of Sally Berkovic’s memoir, Under My Hat, is an allusion both to the hat the author has worn regularly as an Orthodox woman and to the thoughts she keeps underneath it. Berkovic grew up in Melbourne in the 60s and 70s as a child of Holocaust survivors, spent her adult life working and raising a family in London, and lived for significant periods in Jerusalem and New York. She is an astute chronicler of the shifts—first incremental, then seismic—that have transformed the Jewish religious world over her lifetime. Her book, which she describes as a “mashup of memoir, sociology, history and observations,” emerged out of her own struggle to balance her religious commitments and her engagement with the secular world.

Berkovic’s memoir was originally published in 1997 and was republished this fall by Ktav with a new introduction. I took it with me when I went with my family on a retreat organized by Shira Hadasha, one of the synagogues we are part of in Jerusalem. Shira Hadasha is a partnership minyan that sees itself at the vanguard of modern Orthodoxy in Israel. As such, it is part of several of the trends that Berkovic examines in her memoir, and it was, I suppose, ironic that I was retreating from the retreat to read someone else’s thoughts on the very phenomenon in which I was taking part. But I couldn’t help myself. I was oblivious to my surroundings, my head inside Sally’s, and for the two days it took me to tear through her book, the hat I donned was hers.

Berkovic, who currently serves as the CEO of the Rothschild Foundation Hanadiv Europe, illustrates her sociological observations with amusing vignettes drawn from her own experiences, rendered with keen self-awareness. Each chapter of her book is loosely focused on an aspect of Orthodox Jewish life, such as Torah learning, mikvah, synagogue, marriage, and head covering.

A chapter on dating in New York opens with a tone of clever sarcasm reminiscent of A Room of One’s Own: “But I am being unfair. You can be great and married. You can be a great wife. However, that requires finding a husband, which can be harder than being a great wife.” Berkovic offers a glimpse of an Upper West Side synagogue on Friday night—“the hottest dating scene”—where women dress in modestly seductive yet somewhat infantilizing clothing that reflects their own sense of self as a “walking, talking time-womb.” She provides an amusing account of an encounter with an officious and obtuse matchmaker—a friend warns her that she will need to bring her passport so the matchmaker can verify her age, given that “all the thirty-year-olds are claiming to be twenty-seven because the guys have got their pick.”

Here is her quick sketch of one of her many disastrous dates: “He . . . had the look. A certain look of arrogance that told me he was doing me a favour by squeezing me into his busy schedule. A look that said dating was all beneath him, but he did it to help the plight of the Jewish woman.” (I’m not sure that the religious dating scene in the second decade of the 21st century is any better.)

Berkovic, now long and happily married, explains that she wrote her memoir for her daughters, a toddler and a baby when the book was first published, in part because she lost her own mother when she was just 19 and never had the opportunity to ask her about her life. Nearly every chapter is peppered with direct second-person addresses in which she articulates her aspirations for her girls. But the transition to motherhood did not come easily to Berkovic—she recalls staring quizzically at the well-intentioned relative who remarked when her first child was born that now she finally had something to show for herself, as if all her personal and professional accomplishments paled in comparison to procreation.

Berkovic offers an unflinchingly honest if at times comically aggressive description of her struggles to balance motherhood with her intellectual commitments. When her first daughter is born, she does not buy a crib but creates space for her on the bottom of an Ikea bookcase:

I made some room between S and T—I decided we could do without every edition of Delia Smith and Martha Stewart, after all. There were going to be no dinner parties for the next thirty years.

When she goes out one night, leaving the girls with her husband, a friend remarks that it is so good of him to stay with the kids, to which she responds, “Actually, he is their father.” But she is also able to shed the sarcasm and write poignantly about how becoming a parent enabled her to appreciate her own parents more deeply, though she had lost them both many years earlier. Berkovic speculates somewhat wistfully that the fifth commandment, to honor one’s father and mother, is accompanied by the promise of longevity because we need to live long if we are to appreciate what our parents have done for us. Her memoir may be read as her attempt to explain the choices she has made to her daughters and the world she seeks to bequeath to them.

Reading this memoir, I was struck by how little has changed when it comes to the issues confronting Jewish women, but Berkovic’s lengthy new introduction inspires just the opposite reaction. She celebrates the publication of the first works of responsa literature by Orthodox women, which confirms her 1997 prediction that “as women learn Torah, they will begin to transform the meaning of Torah. . . . They can begin to write the books that other women will turn to for advice and information.” Berkovic, who relished her serious study of Jewish texts at Drisha, a women’s yeshiva when she was a single woman in New York, chronicles the proliferation of such institutions, some of which also train women to take on rabbinical roles. She notes, too, that an increasing number of women have completed courses of study to serve as halakhic advisers focused on the laws of family purity. All of these initiatives are taking place in Israel and America, or “Yerushalayim and Bavel,” as she calls them. (“Predictably, England lags behind,” she observes with regret.)

Berkovic wonders about the impact of these developments: “How will women’s proficiency in learning change family dynamics? . . . How will their sons view a woman’s capacity for rigorous study? Will women want a different sort of husband—one who is not threatened or intimated by an educated woman?” She believes that women “gedolot”—giants in the world of Torah learning—will emerge, and with time their status will not be disputed by the Orthodox establishment.

Berkovic surveys other “harbingers of the regeneration of an Orthodoxy deeply influenced by women,” including changes taking place in the synagogue, at the Kotel, under the chuppah, and at the Shabbat table. Her observations extend even to the bedroom, and this too, as the Talmud says, is Torah. She notes that many young couples benefit from new programs to discuss sexuality and relationships, and she comments that the mikvah is increasingly recognized as the first line of defense against domestic violence, since the mikvah lady observes women’s bodies from up close.

Berkovic contends that women’s growing spiritual, political, and communal leadership roles have fueled the modesty wars within the Orthodox community, which she describes as a paradoxical obsession with women’s bodies, dress, and demeanor in the last 20 years. Her remarks seem particularly relevant in light of a new exhibit on women’s modest dress, open through February 2020 at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. “If an alien only relied on certain magazines and newspapers to learn about the Orthodox community,” Berkovic writes, “they might wonder what a woman looks like, let alone if she even exists.” This is an issue she touched upon only briefly in the original edition, when she was, as she now describes herself, “an ill-defined, pregnant 38-year-old woman with an uxorious husband and two young daughters.” Now, from the perspective of late middle age, she observes wryly that “the older woman’s modesty is recast as her greatness as the matriarch of a family. . . . And as she lies in her coffin, her eulogy will recount her modest qualities and how she used them to achieve greatness.” She notes that while the majority of modesty talk is geared toward teenage girls, young mothers who try to look attractive are also berated in some Orthodox communities for not being frumpy enough.

In both the original book and the new introduction, Berkovic engages with the question of why she is still Orthodox in spite of all her frustrations. Her response is especially refreshing in light of the recent proliferation of “off-the-derech” memoirs. “I would argue that women are the defenders of the faith and not the destroyers of the tradition,” she writes. “It is because women care so much that they are trying to find ways to accommodate their needs within Orthodoxy. It would be much simpler to walk away.”

Feminism has erased many traditional distinctions between the genders, but ultimately, we women are still the child bearers—it is we who carry the next generation inside us. Even Moses acknowledged that no one is as invested as a mother: “Why have You dealt ill with Your servant . . . ? Did I conceive all this people, did I bear them, that You should say to me, ‘Carry them in your bosom as a nurse carries an infant,’ to the land that You have promised on oath to their fathers? . . . I cannot carry all this people by myself, for it is too much for me!” (Num. 11:11–14)

The burden of committing ourselves to a binding tradition that for thousands of years has largely not paid heed to women’s voices may tempt one to walk away. But in dedicating her book to her daughters, Berkovic acknowledges that she is staying not just for herself but also for them: “To abandon the beliefs and rituals I have embedded in my daily life would make a mockery of how I raised my daughters and it would betray a trust they had in my principles and actions.”

We are fortunate to have Sally Berkovic to remind us that in a world where the half of the population that historically set the table has now begun citing the Shulchan Arukh—the “set table,” as the preeminent code of Jewish law is known—there is reason for all of us to claim our places at that table.

Suggested Reading

Counting Jews

Tim Grady makes a careful but controversial case about the way Jews contributed to or supported Germany's worst excesses in World War I.

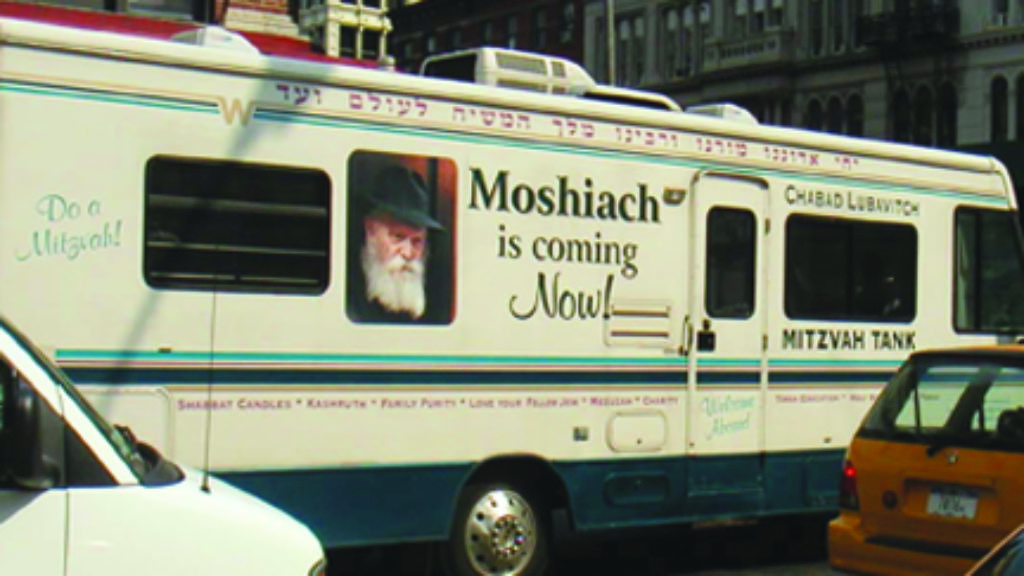

The Chabad Paradox

Despite its tiny numbers, the Hasidic group known as Chabad or Lubavitch has transformed the Jewish world. Not only the most successful contemporary Hasidic sect, it might be the most successful Jewish religious movement of the second half of the twentieth century. But two new books raise provocative questions about it.

Samson Raphael Hirsch’s Attack on Liberal Christian Bigotry and American Slavery

In 1841, Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch leapt into a raging debate between liberal and orthodox Protestants, declaring, “It is high time for the non-Jewish thinker to set aside convenient pre-judgements and to begin to construct Christendom without having to destroy Judaism.”

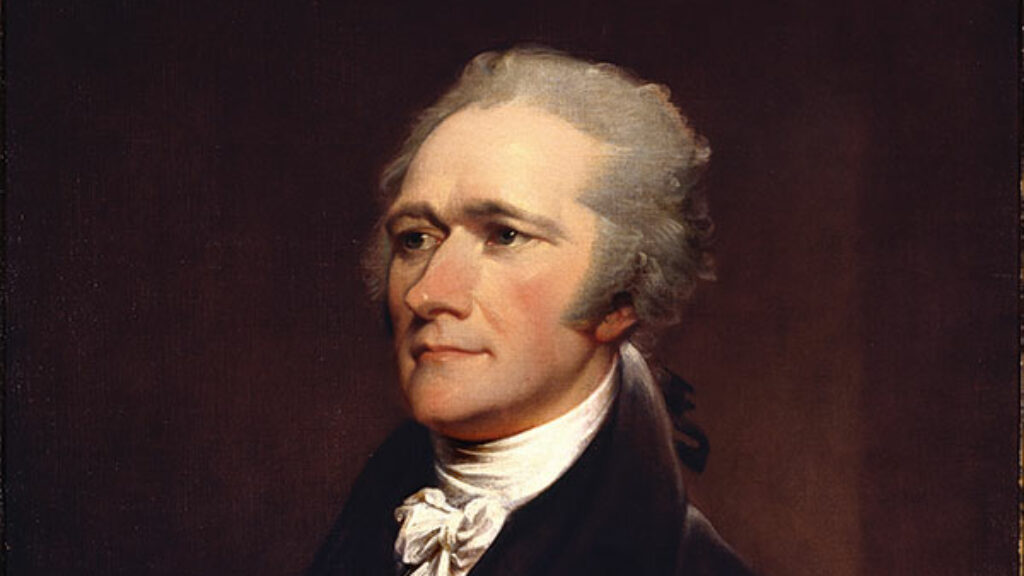

Ten Duel Commandments

Alexander Hamilton was, as the song goes, a “bastard, orphan, son of a whore and a Scotsman.” Was he also a Jew? Well, he did go to Hebrew School in the West Indies, but ...

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In