Our Challah Moment

After decades of bland bakery challah, ours is a great era for challah baking. Indeed, this week, across the nation, including in my own city of Pittsburgh and around the world (Barcelona, Bogota, Johannesberg, Malmo, Montreal, Paris, Rome, Sydney . . . not to speak of Tel Aviv) people are gathering for the annual Shabbat Project group challah baking event to kick off what has become a yearly effort to get more Jews to celebrate Shabbat. But Thursday’s challah bake is just one of several such baking parties.

America’s challah moment coincides with two food movements of more general and popular interest: baking bread at home and a veritable explosion over the past decade of gourmet cookbooks, YouTube videos, and television appearances by Jewish and Israeli chefs and bakers. From Yotam Ottolenghi to Uri Scheft, from Michael Solomonov and Steve Cook of Zahav cookbook and restaurant fame to Balaboosta’s Einat Admony, Jews and Israelis are publicly exploring their ethnic roots through cooking and baking.

In recent years, collective challah baking has expanded beyond the Orthodox community and Chabad, as Reform synagogues and others have joined the party (or thrown their own). This year, there was even a Great British Baking Show-style competition at a local Reform synagogue, perhaps sparked by an episode where challah was curiously called “a plaited loaf.”

Every one of these events—which I have attended variously as a participant, table captain, or Martha Stewart-like demonstrator—has been an event unlike any other I have attended in a life of attending Jewish events. The crowd is (largely) female; the age range is wide, as is the level of expertise. The crowd includes Israeli yordim, secular, affiliated, post-denominational, traditional, and haredi participants.

Moving between tables at a recent event, I spoke with women who were quick to tell me how the “birthday challah” recipe I had demonstrated compared in texture and malleability (which affects the braiding) to what they usually make. Less experienced challah-makers worried the dough was not turning out. The room was loud and happy, full of cross-conversations, not all of them bread-related.

Of course, you don’t need a mass event to bake challah. A brief search on YouTube yields challah videos with millions of hits. Some of them are great for learning techniques, but for deeper understanding and enjoyment, you can’t beat a good cookbook. My challah bible is Maggie Glezer’s A Blessing of Bread: Recipes and Rituals, Memories and Mitzvahs, which was published in 2004. Glezer’s recipe for Czernowitzer challah is simple but always turns out delicious.

A couple of the newest challah-focused book offerings present two sides of the American Jewish coin: assimilationist Jews vs. traditional Jews. Both books are beautiful to look at and have excellent recipes. Both authors also discuss how baking bread for Shabbat fits into their own American Jewish identity.

In interviews about her Modern Jewish Baker: Challah, Babka, Bagels & More Shannon Sarna has explained that she started writing a food blog not to practice her baking but to improve her writing. She insists, as well, that her drive to improve is a fundamentally Jewish part of her personality. It is her intention, through the book, she explained to Mark Oppenheimer of the Tablet podcast UnOrthodox that she wants people to “experience the feeling of confidence that comes with shaping, rolling, and making the bread.”

Yet, she also has an emotional connection to challah. In her introduction, she explains that when her mother died when she was 16, leaving her largely responsible for her two younger siblings, she also took up baking challah with her brother and sister every Thursday night. “Even though my mother wasn’t Jewish (she was a nice Italian Catholic girl from Brooklyn) and I had never seen her make challah, she loved baking and so being in the kitchen connected me to her. One day I opened up her copy of Beard on Bread and I started making challah.”

Needless to say, Sarna was not starting with a traditional recipe given that Beard’s fat of choice is butter and Shabbat dinner usually includes meat. Sarna proudly touts her “mixed up American Jewishness” throughout the book. It is filled with variations on challah—interesting toppings and stuffing suggestions—while excluding any mention of the blessings that accompany the “taking” of challah, when performing the mitzvah.

For Rochie Pinson, author of Rising: The Book of Challah, making the braided loaf is inextricably linked to the traditional religious rituals it is meant to support. Yet, Pinson can sound like a modern life coach. “This is a book for those of us who find ourselves wishing for a return to a simpler time, a slower pace,” Pinson declares in the introduction. Baking challah, she explains, offers “a sense of peace in the moment.” Focus and presence matter, Pinson offers.

A challah dough is a living organism: it requires air, water, attention and intention. Its recipe so closely mirrors the recipe for a well-balanced life, in fact, that as I baked my challah each week, I kept on learning new things about the care and attention required by the living beings under my watch (children, husband, community, and the like).

Like Sarna, Pinson admits early on that she didn’t grow up baking challah and explains how her first handmade loaves turned out badly burnt and misshapen. Unlike Sarna’s book, however, Pinson’s has a religious preamble, which quotes the Lubavitcher Rebbe on the Torah’s designation of challah as reishit arisoteichem (“the first of your dough”): “All we do in this world, however mundane and ordinary it may seem, should begin with an acknowledgment of the Creator and of a Higher Existence.”

I find Sarna’s recipes superior to Pinson’s, though Pinson’s book is visually more appealing and her recipes are more varied. For Pinson, the purpose is fulfilling the mitzvah both of “taking” challah as well as the broader context for which the challah is necessary, Shabbat observance. For Sarna, baking challah is part of her cultural identity, a positive aspect of her American Jewishness. Women of both types will be at challah bakes tonight.

The women from across the Jewish spectrum who gather together at these events are participating in what is more conventionally a solitary experience, held in one’s own kitchen with a good cookbook propped up on the counter next to a bag of flour. But maybe the current fad of group baking can be understood not as innovation so much as a modification of practices that reach back to an earlier time. Indeed, baking used to be only communal, as towns and hamlets ordinarily would have had one baker who baked loaves for everyone. One imagines that the lively, happy pre-Sabbath chatter around the community oven might have sounded something like the conversations at the Great Challah Bake around the world tonight.

Suggested Reading

Loaves in the Ark

A striking tale of pure faith, divine fiat, and free food from Rabbi Moses Hagiz's

Not Just Hummus

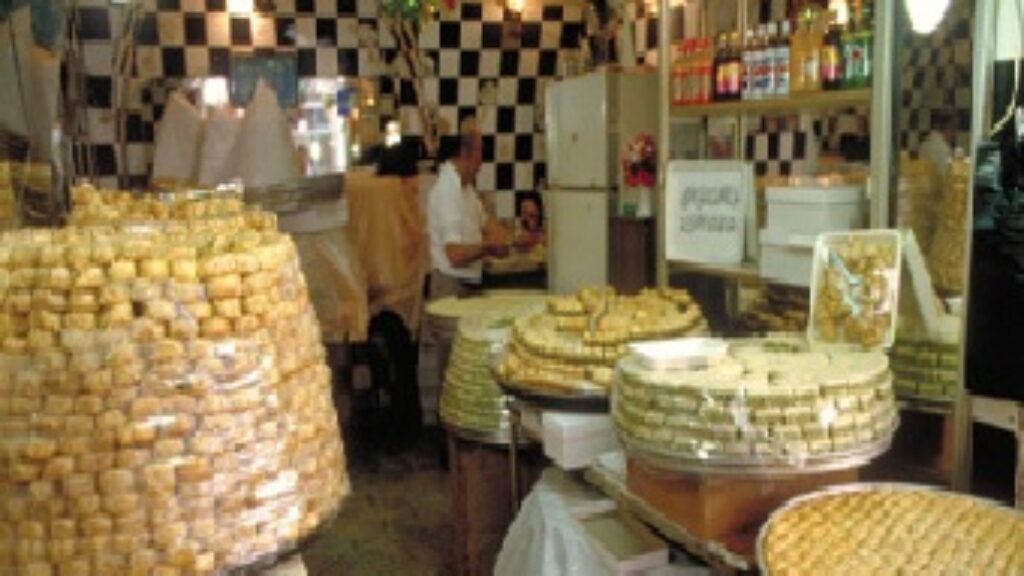

Exploring Israel's culinary culture with two new, very different books about cooking. Jerusalem expats Yotam Ottolenghi and Sami Tamimi have put out a cookbook with remarkable fusions and creations inspired by the holy city, while Abbie Rosner explores the biblical cuisine of the Galilee.

Vegetarian in Vilna

The long, brutal winters and meaty cuisine of Eastern Europe don’t immediately make one think of garden-fresh vegetarian recipes.

Life with S’chug

Einat Admony, who was raised by an Iraqi mother and a Persian father in Bnei Brak and now runs gourmet Middle Eastern fusion restaurants, is a new wave balaboosta.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In