Lawrence of Judea: T. E. Lawrence and the Deal of the Twentieth Century

In his extraordinary 1926 memoir, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, T. E. Lawrence recounted his years during World War I assisting the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire, fighting “in the naked desert, under the indifferent heaven,” part of an “army without parade or gesture, devoted to freedom.” Lawrence described the Middle East as a region that no foreigner could rule forever:

No foreign race had kept a permanent footing, though Egyptians, Hittites, Philistines, Persians, Greeks, Romans, Turks and Franks had variously tried. All had in the end been broken. . . . Semites had sometimes pushed outside this area, and themselves been drowned in the outer world. . . . Only in Tripoli of Africa, and in the everlasting miracle of Jewry, had distant Semites kept some of their identity and force.

The reference by Lawrence to “the everlasting miracle of Jewry” is striking, because Lawrence has always been considered an Arab partisan. The classic 1962 film Lawrence of Arabia focused on his relationship with Faisal, the commander of the Arab Revolt, whose family traced its roots to the prophet Muhammad and whose father, Hussein, ruled Mecca and Medina.

But Lawrence also supported Zionism. He and Chaim Weizmann were close friends, and they held historic meetings and discussions about the Zionist goals. On January 3, 1919, Lawrence brokered an agreement between Faisal and Weizmann, weeks before the post–World War I Paris Peace Conference commenced. The Faisal-Weizmann agreement recognized the national aspirations of both Arabs and Jews and exchanged Arab support for the 1917 Balfour Declaration on Palestine for the promise of Zionist support for an Arab state beyond Palestine. At that time, Palestine comprised both the east and west banks of the Jordan River.

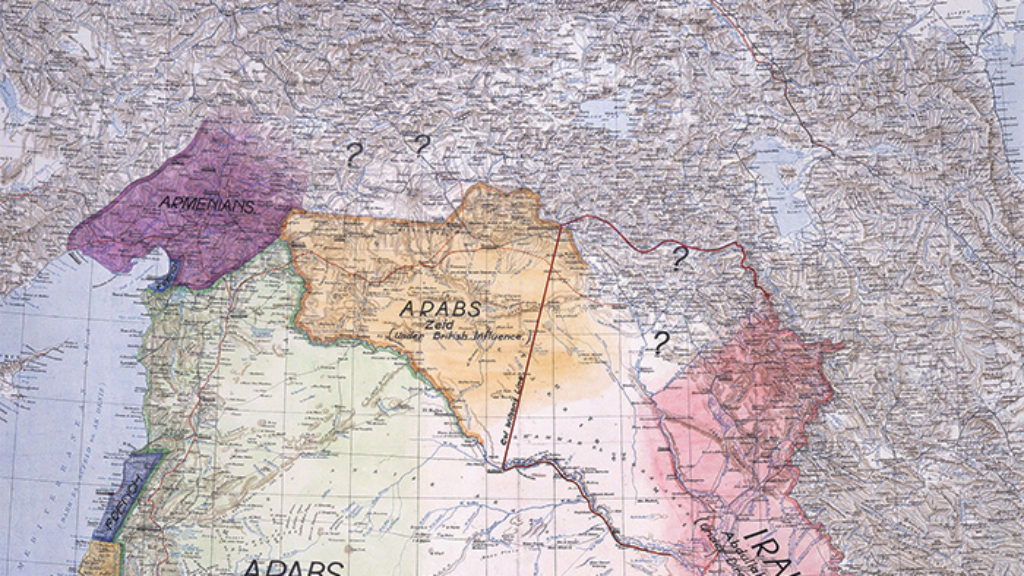

As I noted in my account of that agreement (“Chaim of Arabia,” Winter 2019), Faisal expressly made his treaty with Weizmann contingent on the Arabs obtaining their independence in every respect, as set forth in a memorandum Faisal had provided to the British Foreign Office. But while the Paris Peace Conference recognized Faisal as the spokesperson for the Arabs, it failed to grant the pan-Arab independence he sought. Instead, Britain and France eventually split effective control of the Middle East through the mandate system adopted by the Allies in San Remo, Italy, in April 1920. Under it, Britain received Mesopotamia (now Iraq) and Palestine, while France was given Lebanon and Syria. The French proceeded to expel Faisal from Syria, nullifying the March 1920 designation of him by the Syrian Arab Congress as king of Syria.

In the words of Faisal’s biographer, Ali A. Allawi, with “the disastrous end to [Faisal’s] kingdom in Syria . . . [t]he expectations and hopes raised by the Arab Revolt lay in ruins.” In Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Lawrence wrote caustically that when “the new world dawned [after World War I], the old men came out again and took our victory to re-make in the likeness of the former world they knew. . . . We stammered that we had worked for a new heaven and a new earth, and they thanked us kindly and made their peace.”

Lawrence’s disillusionment after the Paris Peace Conference is captured in a previously unpublished letter of May 14, 1920, to Frederick Claude Stern, Prime Minister David Lloyd George’s private secretary at the conference, which I recently reviewed in the private archives of the Lawrence collection at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California.

At the time of Lawrence’s letter, there was open violence between the Arabs and the French in Syria and Lebanon and a growing rebellion against the British in Iraq. In his handwritten note, Lawrence wrote to decline Stern’s invitation to attend a discussion about Palestine:

I’m afraid I can’t come. Paris gave me a bad taste in my mouth, and so last May I dropped politics, and have had no touch with British or Arabs or Zionists since. I’m out of them for good, and so my views on Palestine are merely ancient history.

I hope you won’t think me rude about it; but it’s rather a sore subject, for since the [1918] armistice our Government has thrown away one chance after another, and now only fighting will put things straight: and I personally don’t want to fight on either side this time!

However, less than a year later, Lawrence received urgent requests from Winston Churchill, the new secretary of state for the colonies, to join a new department formed to deal with the Middle East. After three requests, Lawrence overcame his concerns about what he called “the shallow grave of public duty” and agreed to work with Churchill.

Churchill assured Lawrence he would have a great deal of authority if he joined the effort, and Lawrence came to realize, as he wrote to the writer and activist Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, that it was a “very great chance” to achieve what he had fought for during the Great War and at the Paris Peace Conference.

Lawrence joined Faisal at a weekend meeting on January 8–9, 1921, at the country home of the Earl of Winterton, where long discussions took place concerning the possibility of Faisal assuming the throne in Iraq. Thereafter, Lawrence informed Churchill that Faisal “has agreed to abandon all claims of his father to Palestine,” and Lawrence outlined a plan under which Faisal would receive Iraq, and Transjordan would come under Arab jurisdiction. Lawrence wrote that the advantage of Faisal’s sidelining the question of Syria and excluding claims to Palestine was that:

all questions of pledges and promises, fulfilled or broken, are set aside. You begin a new discussion on the actual positions today and the best way of doing something constructive with them. It’s so much more useful than splitting hairs.

Lawrence told Churchill that the new plan would redeem Britain’s wartime pledges to both the Arabs and the Jews. As historian Sir Martin Gilbert wrote:

In 1915 the Arabs had been promised “British recognition and support for their independence” in the Turkish districts of Damascus, Hama, Homs and Aleppo—each of which was mentioned in the promise—but which did not include Palestine or Jerusalem. Two years later Britain had promised a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine, but with no mention of specific borders. If, therefore, the land east of the Jordan became an Arab state, and the land west of the Jordan . . . became the area of the Jewish National Home, Britain’s pledges would be fulfilled.

On March 2, 1921, Churchill and Lawrence, along with Churchill’s other advisers, traveled to Cairo to hold a conference on British policy in the region, having worked late nights to develop what Lawrence called, in a letter to his friend Robert Graves, “a most ambitious design for the Middle East: a new page in the loosening of the Empire tradition.” Over the course of nine days, Churchill heard from British officials and experts, and Arab delegations (through Lawrence). The conference adopted Lawrence’s plan, with Palestine partitioned along the Jordan River.

During the conference, Churchill cabled Prime Minister Lloyd George, saying, “Fortified by [the] views of Colonel Lawrence,” he planned to meet with Faisal’s younger brother, Abdullah, to discuss establishing him to govern Transjordan. The plan paralleled the one Lawrence had brokered with Faisal in 1919 and had reaffirmed with him in 1921—Arab sovereignty outside a truncated Palestine in exchange for support for the “Jewish National Home” within it.

On March 20, 1921, Lawrence wrote to his eldest brother, Montagu Robert Lawrence, telling him the previous eight days had been “one of the longest fortnights I have ever lived.” But the Middle East he had long sought, he wrote, was finally taking shape:

Everybody Middle East is here. . . . We have done a lot of work, which is almost finished. Day after tomorrow we go to Jerusalem for a week. . . . We’re a very happy family: agreed upon everything important.

Lawrence traveled to Amman to persuade Abdullah to meet Churchill in Jerusalem. As Michael Korda wrote in his 2010 biography, Lawrence “anticipated by more than fifty years Henry Kissinger’s ‘shuttle diplomacy,’ using aircraft to fly from one leader to another throughout the Middle East in intensive bursts of negotiating and persuasion.”

On March 30, 1921, Churchill met with a Palestinian Arab delegation in Jerusalem, headed by the British-appointed former mayor Musa Kazim Pasha al-Husseini, who demanded that Churchill repudiate the Balfour Declaration. Churchill refused on the grounds that it was a binding statement of settled British policy, ratified by the Allied powers, and based on the claims of justice:

It is manifestly right that the Jews, who are scattered all over the world, should have a national centre and a National Home where some of them may be reunited. And where else could that be but in this land of Palestine, with which for more than three thousand years they have been intimately and profoundly associated?

Churchill told the Arab delegation that Zionism would bring “prosperity and happiness to the people of the country as a whole”; that there would be “more freedom, better health, more food and more people”; and that “[a]bove all there will be respect for religions.”

Britain gave Abdullah control of the Transjordan region in April 1921. Faisal was installed as the first king of Iraq on August 23, 1921. Lawrence later expressed his satisfaction with the resolution of the Arab claims:

Mr. Winston Churchill was entrusted by our harassed Cabinet with the settlement of the Middle East; and in a few weeks, at his conference in Cairo, he made straight all the tangle, finding solutions, fulfilling (I think) our promises in letter and spirit (where humanly possible) without sacrificing any interest of our Empire or any interest of the peoples concerned. So we were quit of the war-time Eastern adventure, with clean hands.

Later, in 1927, Lawrence summarized his work with Churchill this way: “I had the knowledge and the plan. He had the imagination and the courage to adopt it and the knowledge of the political procedure to put it into operation.” Lawrence called the settlement “the big achievement of my life” and said he was now satisfied “we kept our promises to the Arab Revolt.”

Several years after Lawrence’s death, Churchill told Parliament that Lawrence had been “the truest champion of Arab rights whom modern times have known.” Together, Churchill said, they had established “vast regions” of independent Arab kingdoms that “had never been known in Arab history before,” while also being “continually resolved to close no door upon the ultimate development of a Jewish National Home, fed by continual Jewish immigration into Palestine.”

Having effectively split Palestine in two, the British next prepared to accept the 1922 League of Nations Mandate over the area—the international recognition of the plan Lawrence had devised. The principles of the mandate were incorporated in what came to be known as the 1922 Churchill White Paper, in which Churchill wrote that over the past several generations, the Jews had re-created a national community in Palestine and that:

it is essential that [the Jewish community] should know that it is in Palestine as of right and not on sufferance. That is the reason why it is necessary that the existence of a Jewish National Home in Palestine should be internationally guaranteed, and . . . rest upon ancient historic connection.

The League of Nations approved the mandate for Palestine on July 22, 1922, incorporating the Balfour Declaration by reference, noting “the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine” and assigning to Britain the responsibility to “secure the establishment of the Jewish national home” there.

Article 25 of the mandate allowed Britain to “postpone or withhold” the application of the provisions of the mandate relating to the Jewish national home “in the territories lying between the Jordan and the eastern boundary of Palestine” and to administer that part of the land as Britain might “consider inapplicable to the existing local conditions.” The Arabs ultimately received approximately 75 percent of the entire area of the British Mandate, and Abdullah became the king of Transjordan the following year.

With his plan effectuated, Lawrence resigned from the Colonial Office, believing that the respective claims of the Arabs and the Jews had now been fairly resolved. On July 8, 1922, Churchill wrote to him:

I very much regret your decision to quit our small group at the Middle East Department of the Colonial Office. Your help in all matters and guidance in many has been invaluable to me and to your colleagues. I should have been glad if you would have stayed with us longer. I hope you are not unduly sanguine in your belief that our difficulties are largely surmounted.

Thirteen years later, when Lawrence died at 46 in a motorcycle accident, Britain had still not established Palestine as the Jewish national home. In 1937, in the face of Arab violence, Britain’s Peel Commission—created to investigate the causes of the violence—proposed that Palestine west of the Jordan River also be divided into another sizable Arab state and a minuscule Jewish one limited to about 15 percent of the original area of Palestine. At a private dinner with Weizmann in 1937, Churchill expressed his “emphatic disapproval” of the partition and warned that, even if it were implemented, “the Arabs would immediately start trouble, and the [British] government would run away again” from even its reduced commitment to the Jews.

Weizmann, backed by his Zionist colleague David Ben-Gurion, led the Zionist Congress in 1937 to accept the British partition proposal in principle, but the Arabs categorically rejected it. In 1939, Britain reneged entirely on its obligation under the mandate to facilitate the Jewish national home, issuing a new plan proposing that Palestine be turned into yet another Arab state, with the Jewish population permanently capped at one-third. Speaking in the House of Commons, Churchill called this “a plain breach of a solemn obligation,” and he forcefully rejected the idea that the Balfour Declaration had been simply a promise to a minority population in Palestine:

[The pledge] was made to world Jewry. . . . It was in consequence of and on the basis of this pledge that we received important help in the War, and that after the War we received from the Allied and Associated Powers the Mandate for Palestine. . . . [It] was not made to the Jews in Palestine but to the Jews outside Palestine, to that vast, unhappy mass of scattered, persecuted, wandering Jews whose intense, unchanging, unconquerable desire has been for a National Home. . . . That is the pledge which was given, and that is the pledge which we are now asked to break.

The House of Commons nevertheless approved the White Paper by a vote of 268–179. Weizmann called it “a sort of Munich applied to us at a time when Jewry is drowning in its [own] blood.” Even with millions of Jews in existential danger, Britain forbade Jewish immigration to Palestine entirely. It ultimately returned its mandate to the United Nations in 1948, with its obligation to facilitate the Jewish national home in Palestine unfulfilled. In the end, Israel was established not by Great Britain but by the Jews themselves. It was done against not only British opposition but an invasion from five Arab armies, including those of countries that owed their own existence to the plan executed by Churchill and Lawrence. That plan had, as one of its underlying principles, a recognition that the Jewish people were entitled to their national home in Palestine as of right and not by sufferance.

Suggested Reading

Chaim of Arabia: The First Arab-Zionist Alliance

Chaim Weizmann regarded his 1919 agreement with Emir Faisal as an epoch-making treaty. That didn’t turn out to be the case, but a century later an Arab-Zionist alliance may be reemerging.

Jerusalem Reconstructed

The Mendelsohns' converted flour mill on the outskirts of Rehavia became a cultural salon, with concerts and poetry readings.

Original Sins

John Judis book about Truman's Middle East policy isn't a rant, but it's not exactly history either.

Zion and Party Politics, 1944

In the summer of 1944 support for Zionism was transformed from a low-risk political gesture to a bona fide election issue. FDR was not pleased.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In