History with a Flourish

What’s all this talk about Jewish material culture?” a distinguished senior colleague asked me a number of years ago. “Is there anything more to it than ‘Here’s a kiddush cup, and, wait, here’s another?’”

Flummoxed by both the question and the disdainful, dismissive tone in which it was cast, I stumbled for an answer, and, while I ultimately came up with one—some drivel about “enhanced understanding”—I suspect my interlocutor walked away from our mercifully brief encounter convinced that, as a field of inquiry, material culture had little to offer other than a capacity for inventory.

Had I had access at the time to Laura Leibman’s jewel of a book, things might have turned out differently. An artful blend of storytelling and analysis, it opens up new arenas of inquiry and provides a series of fresh, canny perspectives on the modern Jewish experience in the Americas. Ostensibly about the history of Jewish women in the United States and the Caribbean from 1750 to 1850, it is also the equivalent of a master class in how thinking with artifacts refreshes and expands the historical imagination.

The Art of the Jewish Family began its life as a series of illustrated lectures Leibman presented at the prestigious Bard Graduate Center in New York. Despite this, and to the author’s credit, it reads and feels like a real book, not a potted version of a verbal presentation, as is so often the case when talk is translated into text. Its pages have the integrity of a book—and a beautifully illustrated one at that. Complementing and enlivening the narrative, not just accompanying it, the volume’s 96 images encompass painting, portraiture, and maps—a bonanza of visual information.

Just when we’ve come to believe we know all there is to know about the early experiences of colonial and federal-era American Jews, Leibman reminds us how much more could be known if only we would deploy a different set of sources and ask a different set of questions. Through five sharply focused case studies, she takes her readers beyond the usual places—New York and Charleston, say—and sets them down in Barbados and Suriname of the 18th and early 19th centuries, whose robust Jewish life rendered that of the American colonies a poor cousin.

Leibman also makes a point of going well beyond the usual suspects who inhabit the standard chronicles. Instead of reading once again about Abigail Franks and Rebecca Gratz, we keep company with Hannah Louzada, Reyna Levy Moses, and Sarah Brandon Moses—an importuning widow, the well-to-do niece of silversmith Myer Myers, and, most stunningly of all, a formerly enslaved Barbadian woman who became an upstanding member of antebellum New York’s Jewish society. We also have the good fortune to meet Sarah Ann Hays Mordecai, who married for love and not money, and Jane Symons Isaacs, who made room for 19th-century Jewish women like herself in the public sphere.

For a host of reasons—poverty, illness, health, racism—these five women and countless others of their era have escaped our attention. Enveloped in silence, they rarely, if ever, appear in the public records. In the absence of formal documentation, earlier generations of historians and genealogists—and, now and again, even family members—had all but given up the ghost when it came to more than the basic facts of when these women were born and when they died. As Leibman evocatively puts it, there are “holes in [the] narrative, as if a silverfish or greedy moth had feasted on the past.”

How, then, can we ever hope to know and befriend these women? Through their things, their domestic possessions: letters, silver beakers, ivory portrait miniatures, “commonplace books” or scrapbooks, broken teacups, and, yes, their family kiddush cups, too. “In each instance,” Leibman writes,

I selected the objects first, and then let those objects lead me to the women. . . . They are objects that surprised me, challenging what I thought I knew. . . . They are objects that seem to deliberately thwart easy answers and instead shift and shimmer in different ways each time I look at or listen to them. . . . They are as complex as the women who owned them.

By subjecting such material to the most searching of inquiries in which even the tiniest detail—the tilt of the head in a black-and-white silhouette or paper cut, the color of the skin in a miniature portrait, the scratches on a piece of silver—is fair game, Leibman coaxes her engaging narrative into shape.

Leibman’s account opens with a letter from 1767, housed in the American Jewish Historical Society’s Jacques Judah Lyons Collection. Amid the thousands of pages of synagogue records, newspaper clippings, circumcision registers, and mercantile accounts lovingly assembled over the course of the 19th century by the good reverend—a “Jewish Casaubon,” Leibman calls him—and donated by his children in 1908 to the American Jewish Historical Society, this particular item sticks out like the proverbial sore thumb.

Written in English by the widow Hannah Louzada to the powers that be at New York’s Congregation Shearith Israel who were responsible for the community’s social welfare, it consists of a handful of poignant sentences, riddled with grammatical mistakes, misspellings, and a total disregard for punctuation, asking for a “little money” to purchase wood and other provisions for the “wenter.” Not much to look at—more of a scrap than a full-fledged document—it could have been tossed years ago by a conscientious clerk. But somehow, through an accident of fate, an instance of serendipity, or mere oversight, the item has stayed put, as if asleep, in the archives.

Leibman reads Widow Louzada’s letter as both document and object. As nimble at interpreting texts as she is at interpreting artifacts, she brings her powers to bear on this fragment of a letter. Her touch awakens it. While she pays close attention to the brevity and bumpiness of its sentences, as well as to their formal supplicatory properties, she doesn’t leave it at that. The letter’s materiality—especially the lovely quality of its handwriting—catches her eye, as does a sprightly curlicue under the widow’s last name. A whimsical expression of personhood, of individuality? Perhaps, but, as Leibman reveals, this stylistic device not only had a formal, Spanish name—rúbrica, which means “flourish”—but also figured as an “essential part of official signatures in Iberia and the Spanish colonies, such that a signature without a rúbrica was deemed less authentic than a rúbrica alone.”

This little flourish adds to and warms our understanding of Hannah Louzada. It’s the first in a succession of subsequent clues uncovered by Leibman that restores Louzada to life. Having come from a place where Spanish rather than English was the norm, Louzada turns out to have been no illiterate but a “woman of quality” to whom the fates had been unkind.

Born and married into wealth, Reyna Levy Moses “was everything Hannah was not.” On the occasion of her marriage at age 17 to her first cousin, Isaac Moses, in 1770, the woman’s uncle, the silversmith Myer Myers, appears to have presented the happy couple with a set of six silver beakers engraved with the couple’s initials and stamped with Myers’s mark. A valued gift, silver was highly prized not only for its beauty but for its utility and “transportability.” Where paintings and rugs just sat there, silver objects were “interactive,” to be trotted out and used. When Jews like the Moses clan fled to Philadelphia during the American Revolution, the family silver came along for the ride.

Reyna Levy Moses’s silver beakers gradually acquired the nicks and scratches generated by continuous use. As one generation after another made a point of keeping the beakers within the family, passing them on to their descendants as both a point of pride and a “form of self-curation,” Reyna’s silver acquired new initials, new homes, and new meaning, “mute testimony to the cups’ transformation.”

After having been in the family since the late 18th century, the beakers left the fold in the mid-20th century. Eventually, these exemplars of colonial silver, of that genre known as “Americana,” landed in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, where their value resided in their provenance as the work of Myer Myers’s hand rather than the property of Reyna Levy Moses. “By becoming ‘art,’” Leibman observes, “the beakers had been stripped not only of much of their original context but of their central role in creating a Jewish family as well.”

Recalibration—but of a different sort—fuels Leibman’s encounter with Sarah Brandon Moses, whose delicately painted ivory miniature, together with that of her brother, Isaac Lopez Brandon, ranks among the American Jewish Historical Society’s rarest treasures. Within its circumscribed space and under glass, Sarah looks for all the world as if she stepped out of the pages of a Jane Austen novel—her skin and neoclassical dress pearly white, her hair neatly arrayed in tendrils that accentuate her liquid brown eyes, her gaze clear and steady.

Though she resembled a lady, gentility didn’t come naturally to Sarah. Like her mother before her, she had been born a slave into the Lopez family of Barbados. Her father, Abraham Rodrigues Brandon, one of the wealthiest men on the island, granted Sarah her freedom when she was three years old, setting her on a course that took her first to Paramaribo, where she converted to Judaism, and then on to London, where she trained at a “Ladies School” for Jewish girls. There, Sarah met Joshua Moses, an American Jew in town on business who, in a curious twist of fate, happened to be Reyna Levy Moses’s middle son. Sarah married him, dear reader, and relocated to New York where she lived, happily ever after—a member in full of New York’s Jewish society—until her untimely death in 1828, shortly after the birth of her ninth child.

Words alone do not sufficiently capture the alchemy of Sarah’s life. What most effectively makes that point is the miniature ivory portrait whose creation both paralleled and abetted Sarah’s transformation from an enslaved person of color into a white gentlewoman. Drawing on the latest innovations in digital photography, Leibman is able to trace, brushstroke by brushstroke, stipple by stipple, the artistic process by which Sarah was endowed with the qualities that made her into a “lustrous and glowing” specimen of white, bourgeois womanhood and, ultimately, the progenitor of a distinguished New York Jewish family.

So total and complete was Sarah’s reincarnation that her granddaughter, an avid amateur historian named Blanche Moses, had no idea that her grandmother had once been a slave. When she held Sarah’s miniature in her hands, Leibman astutely notes, “she saw only its glowing ivory whiteness. The role the ivory had played in marking Sarah as white was no longer visible.”

Lke its subjects, who, appearances to the contrary, led layered lives, there’s even more to Leibman’s account. She has arguments to spare. Gently chiding those who would define a “Jewish object” exclusively in terms of its ritual function and setting, Leibman offers an alternative definition: “The objects in this book,” she writes, “think of Jewishness as something domestic, feminine, and plagued by loss.” As much a rebuke as an exercise in classification, Leibman’s notion of a Jewish object calls on historians to cast a broad net. By her lights, then, a 19th-century teacup festooned with nostalgic images of Jodensavanne, the Surinamese Jewish plantation town, or a Jewish family’s cherished silhouette of a top-hatted American male with a walking stick has as much right to be characterized as a Jewish object as Shabbat candlesticks. What matters most is not label nor genre but how things were used and by whom.

Leibman is keenly attentive to the processes by which history is constituted. Wrestling with the tension—at once institutional and cultural—between absence and presence, the fragment and the whole, she makes much of the notion of archival silence. When confronted with the fissures and fragments of history—and the conditions that gave rise to them—Leibman would have us reckon with and confront them directly. What’s more, surprising things happen when one looks elsewhere for the “shards” of the past:

Turning to Jewish women’s material culture shifts the study of religion from the synagogue to the family and, in doing so, clarifies a key change in Jewish life as “Jewishness” began to dance on the borderline between religion and culture.

Leibman’s account also underscores the ways in which the circumstances and contexts in which objects find themselves—their afterlife—affect their meaning and valuation. We come to understand how much gets lost in translation—and to history—when household items, heavy with use, first assume the status of heirlooms and then land in museum vitrines where, heralded as art rather than history, as collectibles rather than evidence, their backstory disappears.

A harvest of ideas, The Art of the Jewish Family yields a rich ensemble profile of Jewish women of the 18th and 19th centuries, an invigorating consideration of history as a process, and a compelling argument for integrating material culture as a matter of course into any and all historical projects. What binds together these disparate themes, rendering them an integrated whole as well as the stuff of a whopping good yarn, is a mesmerizing tale of transformation, or, better yet, of transmutation—of blackness into whiteness, of household object into artwork, and, most tellingly of all, of absence into presence.

Suggested Reading

Harlem on His Mind

Many Harlem churches that were once synagogues have been torn down to make way for apartment buildings with all the latest amenities.

Israel on the Hudson

An ambitious, new three-volume work attempts to tell the story of New York's Jews from the days of Peter Stuyvesant to the present.

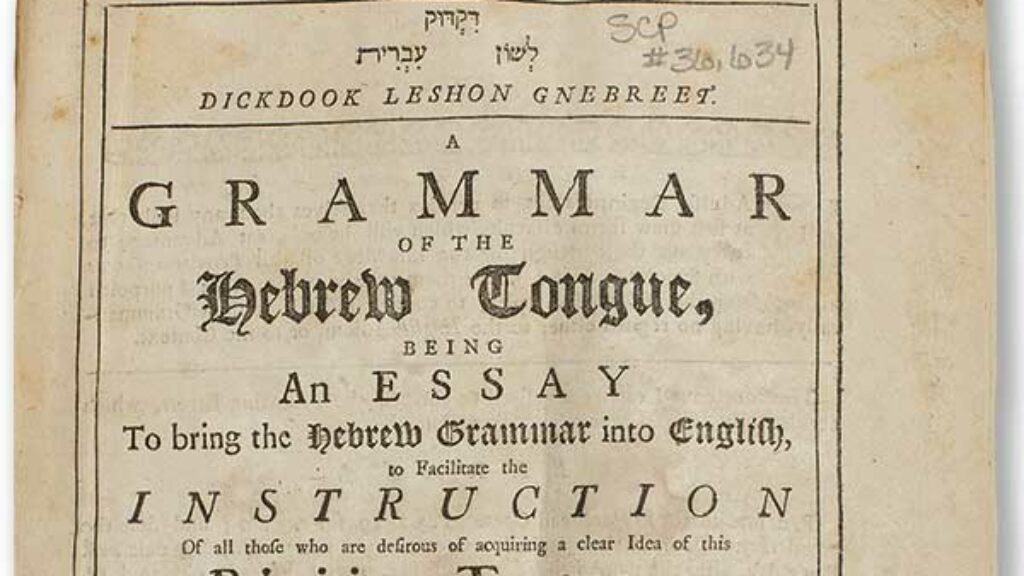

Hebraic America

When Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin sat down to design the Great Seal of the United States they both turned to the Bible.

Inventing American Judaism

Unlike the Jews of Venice, whose charter was anxiously renegotiated every decade or so, American Jews participated in civic life, confidently building themselves a future.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In