The First Amendment and the Vocabulary of Freedom

As it has done to other hallowed traditions, the COVID-19 pandemic upended how the Supreme Court conducts oral arguments. Indeed, our highest court has gone from prohibiting cameras in the courtroom to conducting livestreamed oral arguments over the phone. This has led to some surprising moments, including what’s been called, for lack of a better moniker, Flushgate.

Even more surprising, at least in a substantive sense, were the oral arguments on May 11 in the latest landmark religious liberty case. The case involved two Catholic schools, but it sometimes sounded less like a jurisprudential clash over the First Amendment than a synagogue kiddush. Justices and lawyers found themselves discussing cases, both real and hypothetical, involving sukkahs, Hebrew school, Talmud, and more.

The court’s game of Jewish bingo was not coincidental; it was a sign that a matter of great importance to American Jews had come before the court in Our Lady of Guadalupe School v. Morrissey-Berru and St. James School v. Biel. In fact, the two cases, which the court consolidated, provoked rare broad consensus among Jewish institutions from right to left. Torah Umesorah, the Orthodox Union, and other Orthodox and politically conservative Jewish organizations found themselves on the same side as the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, the Stephen Wise Temple, a Milwaukee Jewish community day school, and the American Jewish Committee, all of whom wrote amicus briefs on behalf of the schools.

Both cases originated in Catholic elementary schools in California. Agnes Deirdre Morrissey-Berru filed suit against Our Lady of Guadalupe School, where she had taught for 16 years, when it refused to renew her contract. Morrissey-Berru had taught her fifth- and sixth-graders reading, writing, math, grammar, vocabulary, science, social studies, and, importantly, religious studies. The school said that its decision was based on her job performance, but Morrissey-Berru, who was in her sixties at the time, alleged age discrimination.

Kristen Biel taught fifth grade at St. James Catholic School, where she, too, was responsible for all academic subjects, including religion. A few months into her second year, Biel was told that her contract wouldn’t be renewed. According to the school, the problem was Biel’s classroom management. Biel, however, said that the school had made its decision after she’d told the school’s principal that she had breast cancer—from which she subsequently passed away—and that the school had discriminated against her because of it. Both schools ultimately responded by setting the details of the case aside and claiming that, as religious institutions making decisions about teachers of religious subjects, they were exempt from antidiscrimination laws on First Amendment grounds.

Even if neither of the teachers was, in any formal sense, a minister, they were tasked with teaching, and even praying with, their students, and, hence, the schools argued, it would be a church-state violation for the courts to intervene in decisions regarding their employment. From the schools’ perspective, the teachers were, in the relevant legal sense, “ministers” and subject to what the court has called the “ministerial exception.” The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals rejected these arguments, hewing to a formalist definition of who counts as a minister, but the Supreme Court may well move in the opposite direction, and for good reason.

At the outset of his remarks on May 11, on behalf of the schools, Eric C. Rassbach argued as follows:

If separation of church and state means anything at all, it must mean the government cannot interfere with the church’s decisions about who is authorized to teach its religion. In this country, it is emphatically not the province of judges, juries, or government officials to decide who ought to teach Catholic fifth-graders that Jesus is the son of God or who ought to teach Jewish preschoolers what it means to say, “Hear, O Israel, the Lord your God, the Lord is one.”

Rassbach was doing more than just sounding an ecumenical grace note when he mentioned the Jewish preschool teacher. He was pointing out that, if it is difficult to decide who counts as a “minister” in a Catholic school, it is even harder in the Jewish context, in which the religious leader preaching from the pulpit is not the only, or even the main, paradigm of religious leadership. Indeed, the amicus brief of the Stephen Wise Temple and Milwaukee Jewish Day School went so far as to claim that “Jewish schools have fared markedly worse” under the Ninth Circuit’s formalistic approach.

In the 20th century, both state and federal governments put antidiscrimination laws in place that restrict the power of employers, including religious organizations, to hire and fire as they wish. But the consensus among courts has long been that they should not be in the business of deciding who is qualified to be a religious leader; that’s where the First Amendment doctrine of “ministerial exception” comes in.

Depending on how you view its constitutional lineage, the ministerial exception descends from 19th-century Supreme Court decisions, if not earlier, but the term itself was first used by a court in 1985. When a court invokes it, the lawsuit is dismissed without any further inquiry to avoid entangling a secular court in religious matters—and the plaintiffs, as a result, do not get their day in court. This is because, as a number of courts have stated, “The relationship between an organized church and its ministers is its lifeblood.”

In 2012, the Supreme Court’s opinion in Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church and School v. EEOC reaffirmed the “ministerial exception,” explaining that to interfere in the relationship between a religious group and its minister would be to “interfere with the internal governance of the church, depriving the church of control over the selection of those who will personify its beliefs.”

None of the parties in the

present cases dispute that the “ministerial exception” is a valid

constitutional doctrine. Indeed, even critics of the doctrine appear to agree

that religious institutions must be given some sort of exception. For example,

when the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission challenged the doctrine back

in 2012, it still conceded that the Catholic Church ought to be exempted from

laws prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sex when hiring a priest. What

is at issue in the

current litigation isn’t the doctrine itself but its scope. Who counts as a

“minister,” and who decides?

The decision in Hosanna-Tabor provided two kinds of indicators for who qualified as a minister. A court could look at the employee’s formal title—including what that title reflected and how the employee used that title—and it could determine whether the employee performed “important religious functions.” But that is easier said than done. Which titles and responsibilities aside from the obvious ones—minister, priest, rabbi, imam—are distinctively ministerial?

The current cases sharpen the question of what a court should do when an employee checks the box when it comes to important religious functions but has no formal religious title. Morrissey-Berru not only taught religion but also led daily prayers and helped plan the monthly Mass; Biel’s teaching included daily instruction in religion, and she joined students for prayer and Mass. Nonetheless, the Federal Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit focused almost exclusively on the fact that neither Morrissey-Berru nor Biel had the formal title or training of a religious leader. Accordingly, the court held that the ministerial exception didn’t apply and ought not to apply to “lay” teachers in religious schools regardless of their job responsibilities.

But during the oral argument before the Supreme Court, many of the justices expressed skepticism as to whether prioritizing formal titles over substantive responsibilities was viable. How could a secular court determine who counts as a “minister” within a given religious community without passing constitutionally prohibited judgment about internal religious matters?

It was precisely this constitutional conundrum that transformed oral argument into kiddush talk. Indeed, the justices and lawyers raised various real and hypothetical cases to see whether a court could really render principled judgments: Could a synagogue terminate a janitor if he erroneously constructed the communal sukkah? What if a yeshiva were to hire a non-Jewish Talmud teacher; would he be a minister? And what about that early childhood teacher who, among other things, teaches children how to say the Shema? Or what about a math teacher—this was Justice Kagan’s example—“who was told to embody Jewish values and infuse instruction with Jewish values?”

On the other hand, if courts

allowed religious institutions to claim any employee as a “minister,” it would

amount to giving them a free pass on antidiscrimination laws, even in cases

that have nothing to do with religious liberty, as Justice Ginsburg sharply

pointed out. In an attempt to navigate between these two alternatives, the Catholic

schools argued that an employee should qualify as a minister only in cases where he or she regularly

performed important religious functions, such as teaching doctrine and

leading prayer. The plaintiffs replied that to ask courts to engage in such

analysis would already violate principles of church-state separation. How could

secular courts decide which religious functions are important and which aren’t?

This argument, however, turned out to be somewhat of a distraction. The reality was that the plaintiffs’ own legal framework suffered from the same constitutional shortcomings. In the plaintiffs’ view, qualifying as a minister required the formal title, the formal training, and the formal use of the term, as well as the important religious responsibilities. Based on their attorney’s theory, Biel and Morrissey-Berru obviously weren’t ministers. However, the framework they proposed would still require courts to engage in precisely the same constitutionally suspect inquiry of deciding which religious responsibilities were important. To apply the term “minister” would require courts to wade, however cautiously, into theological waters.

Recognizing this stalemate also highlights the true stakes of the case. At its core, the ministerial exception is intended to ensure that faith communities retain control over those who personify their religious beliefs. If the government could regulate hiring and firing religious leaders, it would strip these communities of the ability to join together freely in pursuit of shared religious goals. Of course, there is an impulse to make exceptions. But once courts open the door to such government intervention, it becomes increasingly difficult to draw a principled constitutional line to constrain government excess in regulating the relationship between religious institutions and their leaders. Leaders interpret religious doctrine and texts, embody religious ideals, and shape religious values. Therefore, to cede any measure of control to the state over the decision to hire and fire those leaders would give it the capacity to manipulate the very foundations of a religious community.

In some faith communities, leaders receive the title of minister; they stand in front of a church where they preach to and pray with their congregants. But for many minority faith communities—and, in particular, for the Jewish community—the ministerial paradigm of religious leadership presents an awkward fit. This worry has long lurked in the shadows of ministerial exception cases. Indeed, in 2012, a number of justices issued stern warnings about the way in which the language of “minister” could serve to pervert the scope of the exception. Justices Alito and Kagan filed a concurring opinion in Hosanna-Tabor, warning that both the term “minister” and the concept of ordination lack counterparts in many faith communities; they also dropped a footnote highlighting how the term “minister” ultimately captured a predominantly Christian form of religious leadership. Justice Thomas went further, arguing that the prevailing framework for the ministerial exception threatened to “disadvantage those religious groups whose beliefs, practices, and membership are outside of the ‘mainstream.’” And, in the most recent round of oral arguments, Justices Thomas and Alito, as well as the chief justice, once again reiterated those same concerns.

But legal language, if not completely uprooted, is persistent. Its centripetal force pulls courts toward the implicit assumptions of its terminology. Thus, in its decision, the Ninth Circuit assumed a ministerial conception of religious leadership that privileges leadership from the pulpit over leadership in the classroom. Consequently, it viewed teachers of religious doctrine and theology as equivalent to any other teacher unless they had a ministerial title—a decision that pushed the Jewish stakes of the case into full view precisely because it is not necessary for a teacher of Torah to also be an ordained rabbi.

Indeed, for a community that invests so much of its time, effort, and capital in religious education, the idea that constitutional protections would not extend from the pulpit to the classroom just doesn’t make sense. One sees this overarching Jewish communal consensus in the amicusbriefs filed by Jewish institutions in this case from groups that generally find themselves on opposite sides. In recent years, Supreme Court cases that pit religious liberty against antidiscrimination norms have split the Jewish community, with progressive institutions prioritizing the latter over the former and conservative institutions advocating for the reverse. And yet, in this case, even the Anti-Defamation League, a leading supporter of broad antidiscrimination laws, declined to file a brief in favor of the employees, choosing instead to join the ACLU in a brief that, while technically favoring neither party, unambiguously rejected the view that required employees to have a formal religious title to be considered a minister.

Toward the end of the court’s oral argument, under questioning from Justice Alito, Jeffrey Fisher, counsel for the employees, contended that an elementary school teacher who had no formal title but provided only religious instruction would still not be a minister. When Justice Kagan’s turn came, she said that she was surprised: How could a “full-time teacher of religion, teaching religious doctrine, teaching religious practice, teaching religious texts, any of those things” not qualify as a “minister”? How, she asked, could that not be the case given that it was the job of such teachers “to teach religion and to basically bring up the next generation in important understandings of religious doctrine and practice”?

It is generally a fool’s errand to discern the inner thoughts of a Supreme Court justice from his or her questions at oral argument. And yet, is it any surprise that the justice who was apparently a star student of Lincoln Square Synagogue’s Hebrew school in the early 1970s couldn’t understand how a constitutional doctrine designed to allow faith communities to select their most important leaders would exclude teachers? How could a teacher of Torah not be a “minister” in the relevant sense? Fisher did his best to backtrack. If he couldn’t convince Justice Kagan, one of the court’s four liberal justices, there was almost certainly no path to victory. But at that point, it was probably too late; the injustice of privileging formal titles over religious substance was plain.

There is reason to think that the court will ultimately side with the Catholic schools. But the overarching lesson in all of this is that protecting the diversity of faith communities requires not only critical legal decisions but also new legal language. The ministerial exception is not alone in needing a lexical reboot. The Internal Revenue Code still gives a tax exemption to “ministers of the gospel”; courts still invoke “church autonomy” when describing the institutional freedoms afforded religious institutions. Of course, judicial interpretation has increasingly aspired to include all faith communities in these categories. But the fact that our constitutional vocabulary retains vestiges of a majority faith subtly influences the scope of those freedoms.

Faith communities select leaders and build institutions that express their underlying theologies. Consequently, the language and categories of America’s dominant religion do not necessarily map onto the roles and institutions of its minority faiths. Such differences put useful pressure on our ossified constitutional categories, requiring a constitutional language that recognizes different forms of religious leadership.

The American Jewish community has built an extraordinary network of institutions: not only synagogues, but also schools of all sorts, social service agencies, seminaries, think tanks, and other institutions. This is precisely why the justices found themselves returning to Jewish cases again and again. Recognizing this diversity demands a remedy not only for the specific misfit between Jewish leadership and the ministerial exception but for the court’s understanding of religious communities more broadly. Finding a language of freedom that fits the American Jewish community will ultimately help all faith communities pursue their unique visions of all that is sacred and holy.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Discrimination and Identity in London: The Jewish Free School Case

How Britain's highest court misunderstands Judaism.

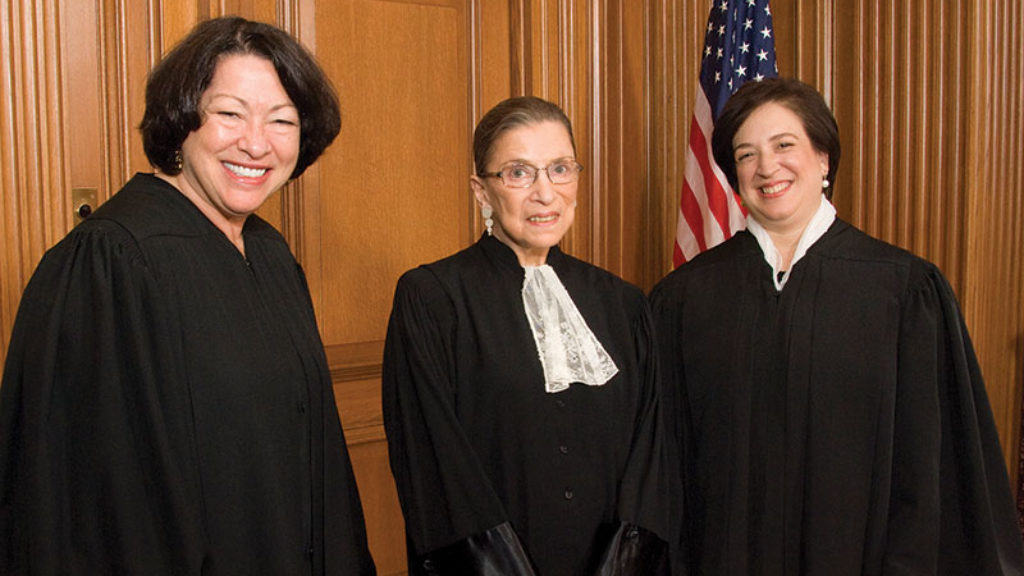

Great Jews in Robes

If Merrick Garland had been successfully confirmed for the seat now occupied by Neil Gorsuch, Jews would have been just one vote shy of constituting a majority on the court.

Old Isaiah

When Woodrow Wilson became the first president to nominate a Jew for a seat on the Supreme Court, much of the opposition to his appointment revolved around his Jewishness.

You Shall Appoint for Yourself Judges

Was the once-head of Israel's Supreme Court a robust defender of human rights or a runaway judge who imposed his political preferences on a nation? Tom Ginsburg explores the legacy of Aharon Barak.

Ryan

Really interesting case, and great job explaining it for lay persons

From what I've read I too think the court will side with the schools, but I hope they do put in place some criteria to apply the minesterial exemption

"the Catholic schools argued that an employee should qualify as a minister only in cases where he or she regularly performed important religious functions, such as teaching doctrine and

leading prayer. ". That seems fair to me, and discourages discrimination at other religiously affiliated work sites, i.e. hospitals, community centers, or storefronts.