(Almost) People

Centuries before Paris became known as the City of Light, it was remembered by Jews as the city of flames, flames which consumed cartloads of Jewish manuscripts following the infamous Trial of the Talmud (also known as the Disputation of Paris) in 1240. The burning of books, from the Kingdom of France to Nazi Germany, is one of many kinds of outrages perpetrated upon the Jewish people throughout their history, yet it has inevitably been experienced as an unusually cruel punishment inflicted upon the body politic. In his opening remarks at the Procès du Talmud, Rabbi Yechiel of Paris was said to have cried, “Our bodies are in your hands even if our souls are not.” The conflagration of sacred books inspired a Hebrew lament that mourned the loss as if it were a real massacre of human lives.

The intimate interrelations between people and books are a remarkable feature of rabbinic society, where Jewish sages are recognizable by the title of their scholarly achievements. Thus, the pious Lithuanian rabbi Israel Meir Kagan is known by the name of his book on the laws of slander, Chofetz Haim (Desirer of Life), and the Galician scholar Yehuda Heller Kahana goes by the name of his work Kuntres Hasefekos (Notebook of Uncertainties). Observing a group of rabbis seated around a Sabbath table, the narrator in an S. Y. Agnon tale says, “They sat one next to the other like holy books in a book closet. What one contained the other lacked, and what one lacked the other contained.”

The flip side of this bibliophilic equation is just as true: Books are (almost) people, too. When a prayer book or other sacred text falls, Jews lovingly kiss it like a child hurt at play. In the synagogue, Torah scrolls are dressed up in sumptuous garb and presented as kings who divide their time between the dignified repose of the ark and the jubilance of a royal procession. On the holiday of Simchat Torah, the scrolls are lovingly embraced and twirled like partners at a ball. When they decay, they are buried alongside scholars who dedicated their lives to Torah study.

For the better part of a decade, Princeton University Press has been publishing a series of diminutive, handsome volumes inspired by the premise that books—religious books in particular, Jewish books among them—have lives, and those lives are worth telling. Princeton’s Lives of Great Religious Books might be seen as the antithesis to the Jewish Lives biographies produced by their old football rival, Yale. If we can have books about lives, why not lives about books? As the series editors and writers are the first to admit, Princeton’s Lives is a conceit. Yet, it is, for the most part, a successful one that reorients the study of religious literature away from theology, philosophy, and philology toward the messy human activities of writing, reading, interpreting, venerating, repurposing, and even reviling and destroying books. This approach quickens the texts and transforms them into something like living organisms.

One way of thinking about the Princeton series is that it is built on an allegory; religious books are treated like saints. Allegories are themselves a quality of many religious books or, to be more precise, the mode through which many such books are read. Perhaps the most famous example is the erotically charged Song of Songs, which has embarrassed, invigorated, and inspired Bible readers for millennia with lines like “Your two breasts are like two fawns, twins of a gazelle, that graze among the lilies.” Ilana Pardes places metaphor and allegory at the center of her account of how a collection of ancient Levantine love lyrics became both holy and mystical; an inspiration for secular and religious poetry; a monastic anthem and a feminist manifesto; a progenitor of great American hits by the likes of Melville, Whitman, and Jimmie Rodgers; and a touchstone for the African American experience.

Pardes argues that the inclusion of Song of Songs in the canon remedied the absence of full-blown eros in the Bible and was based on the conviction that the pastoral wanderings of young lovers in heat might be read allegorically as “theography” instead of pornography. The most famous Jewish advocate of this interpretive strategy was the second-century sage Rabbi Akiva, who professed his love for the book by declaring that “the whole world is not worth the day on which the Song of Songs was given to Israel, for all the Writings are holy, and the Song of Songs is the Holy of Holies.” Even after this bestowal of sainthood, however, the tense relationship between Canticles’ stark erotic sense and religious interpretation remained. Much to the chagrin of pious rabbis, the book’s verses continued to be used in late antique bar tunes. Some medieval Jewish poets even wrote Songs of Songs–inspired homoerotic verse which, they responded to shocked critics, could be read allegorically, just like the original.

A more recent but no less instructive skirmish occurred when the ultra-Orthodox publishing house ArtScroll produced a strictly allegorical translation of the book (“the literal meaning of the words is so far from their meaning that it is false,” the translator’s preface baldly asserted) so that the verse about breasts and beasts is stiffly rendered as “Moses and Aaron, your two sustainers, are like two fawns.” Modern Orthodox readers reacted strongly to this act of poetic injustice, which, they argued, did violence to the divinely inspired text. Admirably, Pardes suspends judgment as she skillfully guides readers through the many twists and turns in the Songs of Songs’ reception history. The most brilliant moments come when she challenges us to redraw the frontiers of allegory, metaphor, and conventional sense. “Are breasts innately more similar to fawns than to Moses and Aaron?” Pardes wonders in a line of inquiry that demonstrates how the song itself, and not just the way in which it has been read, is profoundly allegorical. Fittingly, she concludes her biography with a little-known parable told by Agnon in which the beguiling identity of the Shulamite—the female lover of Song of Songs—is revealed to be the song itself. The beauty is the book.

(The Jewish Theological Seminary of America.)

Notwithstanding the traditional ascription of Song of Songs to King Solomon, or the attempts of Orientalists to reimagine the song’s original poets as rustic beauties, we have no idea who composed its poems. Classical Jewish literature is a canon of compilations with few conventional authors. As a result, the lives of great Jewish books typically do not include well-drawn sketches of their authors, but instead, they quickly turn to the texts’ various readers and interpreters.

One of the exceptions to this rule is the first-century historian Josephus Flavius. In his excellent biography of Josephus’s history of the First Jewish–Roman War (66–73 CE), Martin Goodman focuses on the often infuriating yet undeniably compelling life of its writer, a political acolyte on the make in mid-first-century Roman Palestine. Josephus was appointed to serve as general in charge of defending Galilee; in early 67 CE, he found himself trapped in a bloody cave as his fellow soldiers fulfilled their pact to commit suicide rather than fall into Roman hands. Claiming 11th-hour divine inspiration, Josephus reneged and surrendered to the Romans. He also wisely predicted the unlikely ascension of the Roman general Vespasian to the position of emperor. Josephus witnessed the violent siege and destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE from a privileged vantage point in Roman battle headquarters. What makes Josephus’s life even more absorbing, almost cinematic, is how he spent the remaining decades of his life in a Roman villa, contemplating the triumphant skyline of the empire that had crushed his people and feverishly writing the pained but proud histories on which our understanding of ancient Jewish history still depends.

The long and unpredictable posthumous “life” of The Jewish War continued to be tied up with the life—and, particularly, the reputation—of its author. Like other Jews who wrote in Greek, the rabbis ignored Josephus and his writings, even if some of his anecdotes, such as the Jewish prediction of Vespasian becoming emperor, reappear in rabbinic literature in alternate guise. In fact, The Jewish War and the rest of his books might have vanished entirely were it not for Josephus being cast in a walk-on role as a witness to Jesus’s prophecies. Christians were especially interested in a (doctored) passage in The Jewish War concerning the career of Jesus, and they were animated by a gruesome section describing the depravity of Jerusalem’s destruction, including a horrific act of cannibalism, which they read as a fulfillment of Jesus’s doomsday predictions. Josephus was all but baptized by a string of Christian intellectuals, churches, and empires: He was included in St. Jerome’s On Illustrious Men, a history of Christian literature; a medieval reworking of Josephus’s writings was considered scriptural by the Ethiopian Orthodox church; a Spanish rendition of The Jewish War was dedicated to Queen Isabella of Castile during the height of the antisemitic frenzy leading up to the expulsion of Spanish Jewry.

The reentrance of Josephus into traditional Jewish literature came in the form of an odd medieval Hebrew mashup known as Yosippon, which Italian Jews culled from an assortment of Latin sources. These included Virgil’s Aeneid, Jerome’s translation of the Old Testament, and, still more incredibly, a Christian rendition of The Jewish War that reframed Josephus’s narrative to emphasize divine retribution of the Jews. Yosippon took other liberties, too, most visibly an inexplicable transfer of authorship from Joseph, son of Matthias, to the hardly known figure Joseph, son of Gorion.

Yosippon was included in the Tisha b’Av liturgy and cited in halakhic responsa and was for centuries the primary Jewish historiographical work. Amazingly, the misattribution of Yosippon also gave us the surname of Israel’s founding prime minister, who changed his name from Grün to Ben-Gurion in homage to a book that was read by early 20th-century Zionists as a heroic Jewish battle cry. This may come as a surprise to many contemporary Zionists who think of Josephus as, first and foremost, a traitor to the Jewish people. And indeed, there is a veritable 20th-century tradition of putting Josephus on mock trial for treason. Yet, as Goodman demonstrates, this negative view of the man is mainly a modern phenomenon, reflecting the fluctuating state of the Jew in geopolitics.

A third of the 24 volumes that have been published in the Lives of Great Religious Books series thus far might be classified, in bookstore-ese, as “Jewish interest.” But helpful as it may be, such a designation would obscure the ongoing involvement of Christians in the lives of these eight books. The crisscrossing lifelines of Jewish and Christian readers are fruitfully discussed in all five volumes presently under review, but only in John J. Collins’s The Dead Sea Scrolls: A Biography does the interreligious dynamic drive the narrative.

Admittedly, the Dead Sea Scrolls seem like a poor candidate for a biography. They comprise a large library of ancient Hebrew and Aramaic (and some Greek) texts, rather than an individual book. Moreover, their reception history is almost entirely a story of nonreception: 20 centuries of stony sleep in caves located along the northwestern shores of the Dead Sea before their discovery in the late 1940s and early 1950s. (Curiously, a few Dead Sea Scroll texts were identified in the other great discovery of the modern era, the Cairo Geniza.) And yet, the fragmented life of the scrolls offers more than enough material with which to construct a lively biography. The vibrant, fractious world reflected within the scrolls and the modern world into which they reemerged are best viewed in stereograph, ancient sectarian in one lens and academic partisan in the other.

Collins is a consummate expositor blessed with flawless prose and a scholarly temperament that resists the sensationalizing that has characterized much public writing on the Dead Sea Scrolls. He describes how the scrolls were discovered, preserved, and presented to the public, and he patiently explains the many intricate debates relating to the identity of the scrolls and their significance. Most scholars now believe that the Dead Sea Scrolls originated with an ascetic Jewish group known as the Essenes. However, the solution of this problem has not resolved questions about the Essenes’ connection with other ancient Jews or, for that matter, with present-day Christians and Jews. More contested is the theological significance of references in the scrolls to an arguably Christlike figure and even, some have suggested, an early account of his resurrection. With few footnotes or nested subclauses, Collins walks readers into and out of the academic weeds, recognizing that “the hundreds of thousands of people [who] have waited patiently to catch a glimpse of selected illegible fragments in dimly lighted display cases” are mainly there to “come away feeling that they have touched the past” while enjoying tales of Dead Sea foragers, forgers, and dealers, along with a healthy dose of academic gossip. Remarkably, Collins figures out how to satisfy even that errant desire with dignity and grace.

The modern Christian and Jewish characters who quarreled over the archive as if it were a child caught between two estranged parents are both larger and smaller than life. Already with the formation of the first official editorial team, there was a serious problem with scholarly access. This was later compounded by an excruciatingly slow publication schedule and a mentally ill editor in chief prone to antisemitic outbursts. With the scrolls, the normally tedious arena of academic conferences and publications became a site of heated debate and legal contest, even sucking bystanders into the vortex. Like a respected judge deciding a thorny custody battle, Collins observes the family feud from the safety of the bench, offering pithy commentary and sober judgments. This allows him to emerge with his faith in humanity, and academia, largely intact and with confidence for the future of Dead Sea Scrolls scholarship.

I regularly teach a college course called Great Jewish Books, which spans the canon from famous biblical books to more obscure medieval tomes. Like an end-of-the-year top-10 list, my syllabus has provoked some good-natured controversy among colleagues about what deserves to be called a great Jewish book, a Jewish book, and, for that matter, a book at all. While they may seem inconsequential, questions about the confessional identity and material form of religious texts can be quite revealing. On this front, we might note that the Lives of Great Religious Books series includes scriptural mainstays like the Koran and Lotus Sutra and also more topically or materially unusual choices like C. S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity, Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Letters and Papers from Prison, and the Passover haggadah.

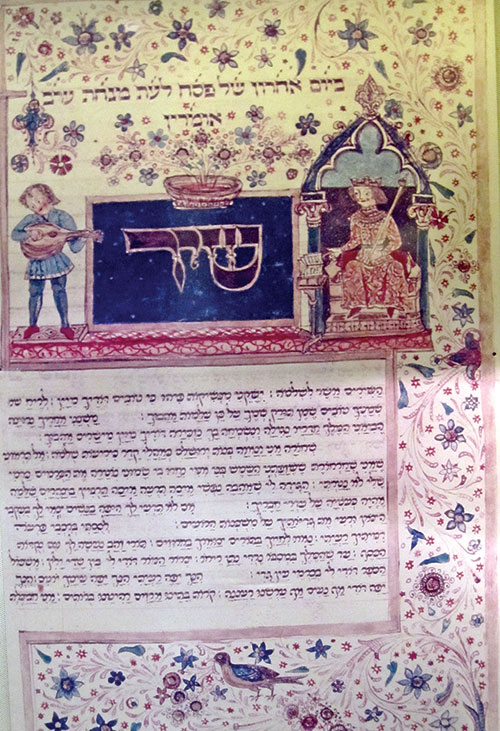

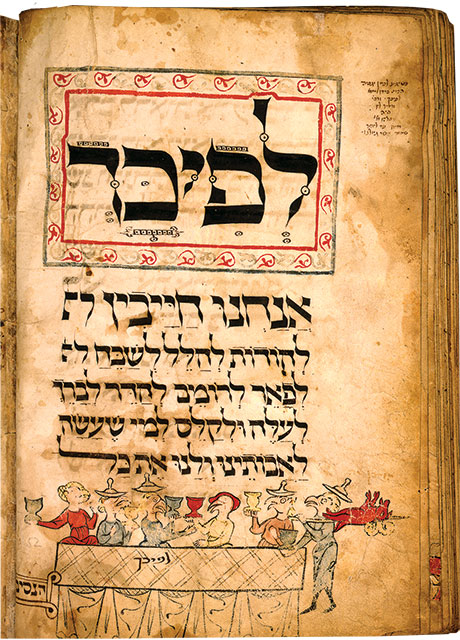

People are often surprised to find the haggadah listed in my course syllabus as it is not really a book for reading but a ritual instruction manual with easy-to-understand directions and a catchy 13th-century mnemonic to help run the Passover Seder. Rarely consulted in the rest of the year, it is thoroughly embedded in this family affair. Perhaps this justifies Princeton’s decision to commission an anthropologist rather than a rabbinics scholar or medievalist to write the life of the haggadah. There is a price for this choice, paid in inaccuracy (the freestanding haggadah is incorrectly claimed to have first emerged only in the 13th century) and naïveté (a Nightline segment about the famous Sarajevo Haggadah is uncritically quoted at length). But to be fair, there already are scholarly reception histories and bibliographies of the haggadah readily available, and Vanessa Ochs’s folksy tone and humane touch are well suited to the task of telling the distinctly human account of the Passover haggadah.

Following anthropological

convention, Ochs begins with a well-crafted arrival scene: a visit to the luxury

apartment of a collector that ends with Diet Coke spilled on his valuable haggadot

and a lesson learned about “that place of vulnerability, subject to wine spills

and the assault of matzah crumbs,” where the haggadah “choreographs the

transmission of particular memories and inculcates sensibilities.” Ochs’s

biography grows stronger as it approaches the ethnographically accessible

present. There are smart reflections on consumerism and promotional haggadah

printing (“the marriage between advertising and sacred texts did not deviate

from Jewish practice; it was a logical outgrowth”), the unique aura of

Holocaust-era haggadot (“they are treated as material survivors—as

objects haunted by memory”), and the great variety of mimeographed kibbutz haggadot,

which include everything from antireligious screeds to records of babies born

on the commune. Herself a scholar of contemporary ritual, Ochs concludes the

study with a discussion of recent trends in DIY haggadah making and a

speculative peek ahead at the brave new world of sci-fi haggadot. Even

when she imagines this distant future, Ochs does not see a post-human dystopia

but a cheerful, convivial future where “a Haggadah portal may

enable a Chad Gadya (An Only Goat) sing-along in all the world’s

languages” and “reciting ‘let all who are hungry come eat’ could . . . activate

automatic contributions to food banks.”

Since the seventh century CE, Jews have been known as a people of the book. Conventionally, that book is the Torah, but since the Middle Ages, the wellspring of Jewish life has been the Babylonian Talmud rather than the Hebrew Bible. Indeed, one of the factors that led to medieval Jewish book burnings was the church’s realization that Augustine’s doctrine of Jewish witness, in which Jews are to be tolerated in Christendom because they represent the Old Testament, was unfounded. As Barry Wimpfheimer explains in his biography of the Talmud, the Paris trial “indicted the book as though it were a person. . . . Personification of the Talmud made its body a substitute for the body of Israel.” More than any other Jewish book, it is the Talmud that most requires a vibrant biography of its life as the material object, intellectual obsession, and human expression of the people of the book.

Such an account might begin with a vivid portrait of the Talmud’s Babylonian home, located in the heart of the Persian Empire at one of the most fascinating times in world history. A biography of the Talmud would describe the cultural factors that led to the creation of this most astonishing text—astonishing in terms of its intellectual sophistication, thematic scope, and literary triumph. It would focus on the great diversity of materials on which the talmudic text has been inscribed, including manuscripts, printed editions, and digital databases, and it would probe the significance of each of these material phases for understanding of the Talmud’s momentous trajectory from past to present.

A life of the Talmud would take stock of the text’s dizzying reception history as it was read and reread by Jews in virtually every inhabited corner of the Earth, and it would chart the major schools of interpretation that formed and disbanded as intellectual trends rose and fell. A talmudic biography would also study the Talmud’s effects on Jewish societies around the globe, on Jewish literatures in their many languages and genres, and on Jewish peoplehood in the diaspora and the State of Israel. As with the other Princeton biographies of major scriptural traditions, like Richard Davis’s volume on the Bhagavad Gita, this would be a gargantuan task. But, as evidenced by this and other successful volumes in this series, it is a job that can be done and one that the Talmud, as a great religious book, demands.

Barry Wimpfheimer’s crisply written contribution to the Princeton series is many things: an extended panegyric to the Talmud, a collection of clever talmudic readings, and, most of all, an example-driven introduction to talmudic discourse and interpretation and the legal literature that it spawned. Indeed, the decision to structure the book around a limited set of exemplary passages is a welcome one, distinguishing this volume from other introductions to the Talmud on the market. And yet, the one thing that The Talmud: A Biography is not is a biography of the Talmud.

Wimpfheimer’s book gestures

toward the biographical conceit of the series, productively when discussing the

Talmud’s personification in the Disputation of Paris and problematically when

applying a kind of rigid developmental psychology that segments the Talmud into

three separate stages, the “essential,” “enhanced,” and “emblematic.”

Wimpfheimer’s “essential” Talmud refers to the historical, original talmudic

text, yet, instead of an evidence-based discussion of the rise of rabbinic

Judaism and its Talmud, we are treated to lengthy interpretations of rabbinic

foundation myths. What is more, there are striking historical errors in the

account, such as the claim that “the Babylonian Talmud attributes ideas to

rabbis who lived until the end of the fourth century CE.” (The amoraim

lived to the end of the fifth century, and a few named talmudic sages

flourished into the sixth century.) Inexplicably, new research on the historical,

political, cultural, and religious contexts of Babylonian Jewry is not used to

reconstruct the original Talmud but is instead relegated to a tag end

discussion of “new discourses,” where it finds its place alongside Hermann

Cohen and Emmanuel Levinas.

In his discussion of the “enhanced” Talmud, Wimpfheimer considers the fate of the work once its status and authority evolved from the local exercises of Babylonian scholastics into a piece of (Jewish) world literature that was the focus of extensive commentary and legal application. Unfortunately, we are not led to understand how this hard-won process was fought. There is also hardly any engagement with the dynamics or significance of the transition from oral transmission to handwritten manuscript, and even the book’s somewhat lengthier treatment of printing does not explain what moveable typeface meant for printers and what it wrought among readers. Some major schools of interpretation are usefully surveyed, though, like the Talmud itself, these too are placed into three limiting boxes: “traditional” Ashkenazi, “intellectual” Sephardi, and Provencal “meditators.” There is not a single mention of pilpul—the highly influential and highly controversial dialectical movement that flourished in 16th-century Poland—nor do we hear a word about the “Sephardic method” of close reading associated with Isaac Canpanton and, later, the Spanish exiles. Reference to the talmudic character of the Zohar is suggestive but unrealized, while a discussion of the talmudic genealogy of Jewish standup (part of the “emblematic” Talmud) is entirely unmoored, resting on a single article in Entertainment Weekly. To put the matter bluntly, The Talmud: A Biography wastes a precious opportunity to descend into the Talmud’s messy, fecund life, and thereby telling one of the Jewish people’s central stories.

One of the most frequently quoted sages in the Talmud was a colorful fourth-century rabbi named Rava, who lived within the environs of the Persian imperial capital of Ctesiphon, along the Tigris River. In one of many memorable maxims attributed to him, Rava complains of those “foolish . . . people who stand before a Torah scroll but do not stand before a great man.” The practice of rising for the Torah is a beautiful old Jewish custom that reflects a reverence for scripture so deep it treats dead parchment inscribed with holy words as if it were an esteemed person worthy of respect. In his reappraisal of the practice, Rava argues that, really, it is the sages who most deserve such displays of respect. Surprising as it may seem for a rabbi to favor mortals over the divine Torah, Rava’s preference is eminently understandable: Without the lives of great scholars, there are no lives of great religious books.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Inerrant or Oblique?

John Barton has written a wonderful book about the Bible for believers and nonbelievers alike.

Who Is David?

Scholars and lay readers remain fascinated by the biblical stories of David and the history behind them, as a new batch of books shows.

Inside or Outside?

After the discoveries of the Cairo Geniza and the Dead Sea Scrolls, scholars of Judaism slowly began to reconstruct the 400-year period separating the latest parts of the Hebrew Bible from the earliest rabbinic compilations.

Lost in Translation

When Aviya Kushner encountered the Bible not in Hebrew, but in translation, she was shocked at how different it was, both in form and in substance.

gersho hepner

THE SONG OF SONG’S HEROINE WAS THE SONG OF SONGS

Agnon unshyly once identified the lovely Shulamite,

one of the characters in the Song

attributed to Solomon, the wisest king --an attribution

that I think helped Agnon to come up with his great solution,

being almost certainly quite wrong!----

as the very Song of Songs the unknown author chose to write.

By attributing the Song to Solomon the poet

managed magically to conjure

anthropomorphically by means of words the state of being in

the highest form of love, performing which most surely cannot be a sin

when lovers satisfy their hunger

with words. It takes a man as wise as Solomon to know it.

Only Solomon, described as wisest person in the world,

could have from Hebrew words created

a song who verbal beauty literarily was comparable

to a lovely lady, called the Shulamite, a parable

that links her to where she’s equated

in Proverbs to a valor girl whose beauty this king superpearled.

by doing this anticipating how much later Jewish books

provided rabbis with their names,

so that that they would be known by all not by the ones that were bestowed

on them when circumcised, but by the holy books where they’d download

their wisdom, books they wrote their frames

encapsulating them just like Shulamite, although not for their looks.