The Law of the Baby

Mara Benjamin was not raised to “regard motherhood as destiny and aspiration.” Her “feminist mother emphasized meaningful and successful work—not to the exclusion of motherhood, but not subordinate to it, either.” But she found that her own experience as a mother did subordinate everything else in her life, including, above all, her individual autonomy. “In the early days and months of first having a baby,” she writes, “the raw, immediate assault on my freedom—a freedom I had not even known I had previously enjoyed—struck me with overwhelming force. No sooner had this baby, this stranger, appeared than she held a claim on me.” She found herself subject to what she calls “the Law of the Baby.”

Benjamin does not regard this law as a burden, nor does she idealize parenthood. Instead, she provides a deeply philosophical account, in loving, sometimes humorous detail, of what it is like to live under the Law of the Baby—and uses it, together with incisive readings of classical Jewish texts, to explore the nature of obligation in Judaism. In a stunningly new approach to maternity, Benjamin does not focus on the bodily, biological experience of motherhood. She does not discuss pregnancy or birth. Indeed, she draws equally on her experiences as both a biological and adoptive mother. In one particularly beautiful passage, she describes the difficult bureaucratic and judicial process of adoption. But, instead of complaining, Benjamin asks a striking, counterintuitive question: “Why didn’t I have to take on the responsibility of being a mother to my biological daughter voluntarily, publicly, and of my own accord, as I had with my nonbiological daughter?”

It is the inescapable centrality of the obligation of a parent to her child that lies at the heart of Benjamin’s thought: “Maternity presents a primal experience of being subject to rather than master over.” She goes on to describe the life of a mother with a new child in vivid phenomenological detail:

My obligation was, on the most literal level, to locate myself in proximity to her and to do things for her, night and day. Her body demanded compliance. . . . It no longer made sense to get myself ready for bed when I knew that just a short while later I would be up again. . . . These shifts in my relationship to time, the material world, and my own autonomy comprised the becoming of an obligated self, a self radically bound up with someone else.

Her own experience of being comprehensively obligated brings Benjamin back to the long-standing tradition of Jewish thought.

Since the Enlightenment, Jewish thinkers have struggled to explain the value of being obligated in a Western culture that has given the highest priority to the value of self-determination. In contrast to other feminist Jewish theologians such as Judith Plaskow or Rachel Adler, Benjamin does not argue in favor of any particular approach to Jewish law, neither advocating for traditional observance nor promoting halakhic innovation. Her depiction of the self as obligated calls to mind Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik’s Halakhic Man. In contrast to the homo religiosus of the classical religious sciences, the commitment to commandments here serves as a model for a person devoted to others. Soloveitchik describes “halakhic man” as an “exoteric,” outgoing person: “His face is turned toward the people.” Although Benjamin does not refer directly to Soloveitchik, her exploration of the self as chiefly constituted by obligation places her in close philosophical proximity to this Modern Orthodox thinker, whose portrait of a person being commanded clearly featured a Jewish man. Both philosophers examine the commanded person, albeit in oppositely gendered language. Yet Soloveitchik, I imagine, would have agreed with Benjamin’s daring formulation that “to be a Jew . . . is to be obligated.”

The philosophy that emerges from Benjamin’s central insight is one that builds on other 20th-century European Jewish thinkers, most notably Hermann Cohen, Franz Rosenzweig, Martin Buber, and Emmanuel Levinas. With Cohen, she shares the centrality of commandment and of being commanded. The exploration of the parental situation aligns her philosophy with Buber’s idiom of “I and thou,” as well as Levinas’s complex notion of the “other.” Her key example of a parent being commanded by the immediate needs of a small child bridges the gap between commandment as a core theme and interpersonal relationships as the central frame of reference in Jewish philosophy. “Like modern Jewish thinkers before me,” she writes, “I find relationships theologically productive.”

Following Rosenzweig—though without mentioning him here—Benjamin also reclaims for Jewish theology the word “love,” so overused by Christianity. Her reflections on the deep rewards of parenthood, together with its inescapable frustrations, provide a window into “the seamless continuity between God’s affection and fury as portrayed in the Hebrew Bible.” She writes that “God’s love for his people is maternal love amplified: dynamic, volatile, and keenly attentive.”

Benjamin’s discussion of one’s relationship with “the other” clearly echoes Levinas, but her concern is not with ethics or the Levinasian notion of responsibility for the otherness of the other. Instead, Benjamin contemplates otherness as an internal dimension of the parental relationship. She explores the ways in which one’s child both is and is not an “other,” neither a part of one’s self nor wholly separate:

Rather than insisting on the irreducible alterity of the other, or a monism that denies radical alterity, we find here an intersubjectivity that encompasses both.

This helps her illuminate the human link to the divine other in Judaism:

The interconnection, difference, and responsibility that characterizes the asymmetrical relationship between God and human beings is given texture by the work of caring for and raising a child.

Benjamin’s depiction of perpetual parental availability sounds exaggerated to the practicing “good-enough” mother. Here, too, the conversation with Soloveitchik may be instructive. Observance is required, not perfection. Obligation need not entail overdoing.

In any case, Benjamin’s vivid descriptions of the commanding power of the baby do not detract from her deep phenomenological insight into the way in which our obligations form us. Benjamin describes the change she felt after becoming a mother: “Even when I was by myself, I could no longer feel truly solitary.” This is a feeling shared by many mothers, but it is especially feminist mothers, it seems, who are taken by surprise that motherhood would overwhelm their freedom. Benjamin is among the first to reflect philosophically on this experience. To be obligated in this way, she argues, is not merely to recognize the force of external commandments; it is a state of being, or rather, a mode of acting.

Benjamin’s rich account of parental obligation as a primary experience should also be read by contemporary Christian theologians who have reframed the old debate about the relationship between law and grace. Christian thinkers who have reevaluated the importance of Torah (for Paul and themselves) and rethought the ethics of commandment might read Benjamin so as to reconsider the depth and importance of the spiritual experience of obligation.

Talking about “the Law of the Baby” as a way of thinking about the source of our obligations is certainly refreshing, and Judaism and Christianity have long used parental metaphors to help understand the biblical God’s love and fury. Still, it is doubtful that either the commanding force of a helpless infant or the image of God as a raging and worried parent can guide Jewish thought past what still may be its central challenge: the end of theodicy after the Shoah.

Indeed, such familial metaphors might even be seen to turn us back to the kind of naive theodicy that Irving Greenberg, Emil Fackenheim, and others so incisively rejected. It would be fascinating to see Benjamin discuss Greenberg’s critique of a God who does not fulfill the obligations of the covenant or Fackenheim’s notion of Jewish continuity as a primary obligation. These are dialogues she does not explore in The Obligated Self, but it is a mark of the achievement of this book that one has such thoughts.

Unapologetic, intellectually riveting books have been written before about commandments and being commanded, but this is the first that is at the same time a moving account of the adventures of parenting—a central aspect of Jewish, indeed human, life—philosophically described with humor and thoughtfulness.

Suggested Reading

Heschel Transcendent

Abraham Joshua Heschel’s intellectual peers included Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, Reinhold Niebuhr, and the Lubavitcher Rebbe. His main thought, Shai Held argues, was of transcendence.

Nostalgia for the Numinous

In the beginning there were the angry atheists. Terry Eagleton is more melancholy: “Atheism is by no means as easy as it looks.”

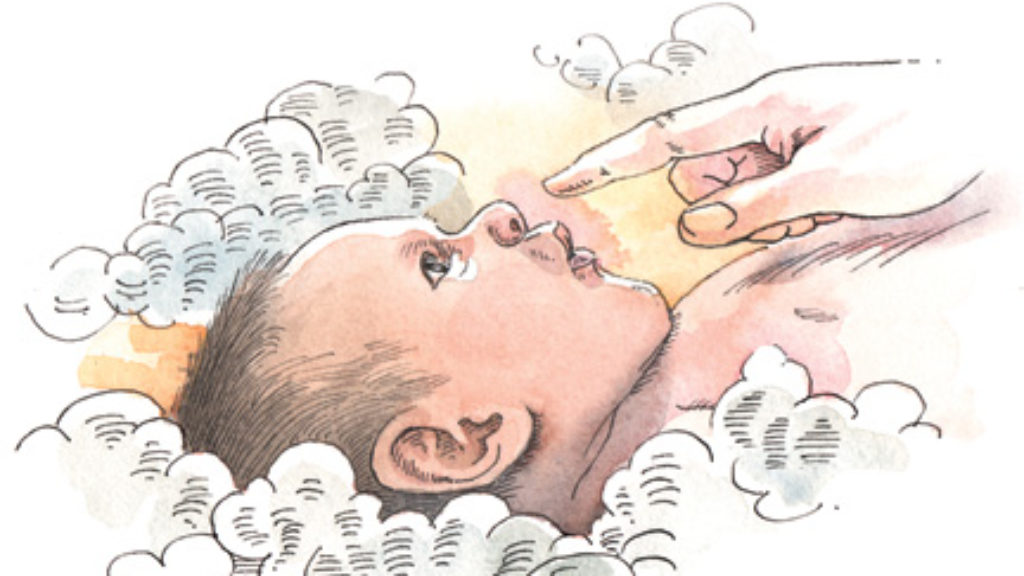

How the Baby Got Its Philtrum

The idea of learning as a recovery of what we once possessed is what makes Bogart’s bubbe mayse, and ours, so memorable: We can all touch that little hollow and feel the impress of forgotten knowledge.

Wisdom and Wars

If it were fiction, Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom would be the greatest English war novel.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In