The Danish Prince and the Israelite Preacher

To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven,” Kohelet says (Eccles. 3:1). There is probably no more familiar verse from the biblical text that we read at this particular season, on the intermediate Shabbat of Sukkot, as the life-sustaining rains begin in the Land of Israel and, in the lands of Ashkenaz, the exuberant notes of Hallel segue into autumn’s dying fall. It’s a puzzling choice of text because the text itself is puzzling, full of apparent contradictions. These contradictions are, in turn, reflected in rabbinic attempts to understand the tradition of reading Ecclesiastes on Sukkot. Thus, we find the great sixteenth-century rabbi Mordechai Yaffe arguing that we read it during Sukkot because it exhorts us to rejoice in the portion that God granted us in the season of our joy—“There is nothing better for a man than that he should eat and drink, and make his soul enjoy pleasure for his labour. This also I saw, that it is from the hand of God” (Eccles. 2:24). Yet his younger contemporary Azaryah Figo argued precisely the opposite: we read this particular book on Sukkot to remind us of our own mortality—“It is better to go to the house of mourning, than to go to the house of feasting; for that is the end of all men, and the living will lay it to his heart” (Eccles. 7:2). Ecclesiastes contains sublime and moving poetry, but it cannot seem to make up its mind.

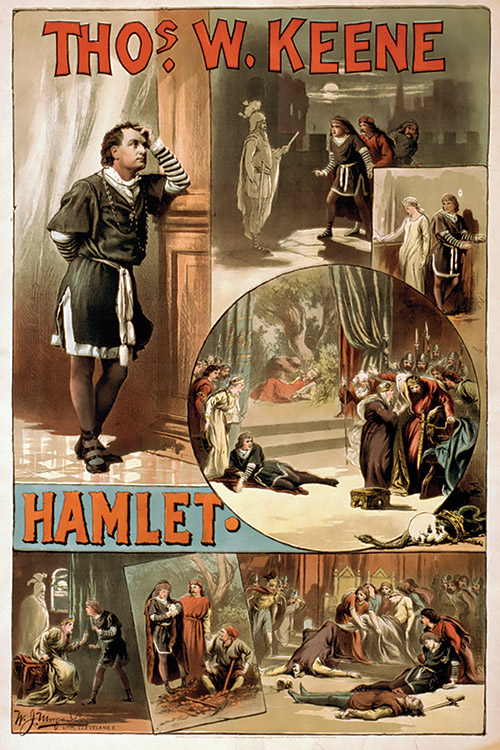

When I reread it recently, though, what struck me immediately was how much it has in common with another canonical text with sublime and moving poetry about a man who cannot make up his mind. Consider:

How weary, stale, flat, and unprofitable

Seem to me all the uses of this world! (Hamlet, act 1, scene 2, lines 133–34)

Were they not written in iambic pentameter, I wonder whether anyone could tell if the speaker were the Danish prince or the Israelite preacher.

Over and over in Shakespeare’s peculiar tragedy, his title character echoes the themes and tropes of one of the most peculiar books in the Hebrew Bible. Even Shakespeare’s word choices resonate better with the original Hebrew than with the biblical text that Shakespeare knew. “Mah yitron la-adam be-chol amalo” (Eccles. 1:3) is rendered by the 1917 JPS translation as “What profit hath a man of all his labor?” The Geneva Bible of Shakespeare’s day renders the same verse as “What remaineth unto man in all his travail.” The Geneva Bible renders “kol ha-d’varim y’gei’im: lo yuchal ish le-dabeir” (Eccles. 1:8) as “All things are full of labor: man cannot utter it,” which scholar Michael V. Fox persuasively argues should be translated as something like: “All words are wearisome: man cannot speak.” The modern translations of Ecclesiastes sound more like Hamlet than Shakespeare’s Bible did.

When I realized this, I compiled a collection of plausible cross-references between Hamlet and Ecclesiastes so easily that I had to stop and ask myself the profit of this labor. The comparisons are striking. Hamlet’s death wish—“’tis a consummation / Devoutly to be wish’d,” (Hamlet 3.1.62–63)—his inability to feel pleasure—“I have of late,—but wherefore I know not,—lost all my mirth” (Hamlet, 2.2.261–262)—his misogyny—“frailty, thy name is woman!” (Hamlet, 1.2.146)—all find their echo in Ecclesiastes (or vice versa). On the other hand, Hamlet was a brooding and melancholic youth who would naturally be drawn to feelings of futility that Ecclesiastes expressed. Is there anything more to the comparison?

I think there is. It may be folly to try to say anything new about Hamlet, quite possibly the most studied text in the English language, but as both works tell us, the wise man and the fool come to the same end anyway. The more I read Ecclesiastes through the lens of Hamlet, the more the book came into focus, not as the work of traditional wisdom literature that it initially seems to be but as a work that shows both traditional wisdom literature and the new discipline of philosophy to have failed. Perhaps even more surprising, Hamlet (and Rashi) showed me a way to read Ecclesiastes as more than a collection of beautiful but unconnected sayings. It helped me to read it as a coherent and moving narrative in its own right.

Hamlet, famously, is a character who escapes the bounds of his play to become as real and as alive as we are, but in this, as Hamlet himself might put it, he “but seems.” Though he stages a play of his own, Hamlet is bounded by the nutshell of the drama that bears his name, a play that he did not write. Hamlet, in other words, is not Hamlet. I see the same distinction in Ecclesiastes, with the same potential for confusion. Most of the words of Ecclesiastes are spoken by someone whom, following Fox, I will distinguish from the book by calling “Kohelet.” But though he frequently appears to be the author, Kohelet, too, is a character.

Who is he? Kohelet is traditionally identified as King Solomon—and for good reason. At the outset of Ecclesiastes, the author announces the words to come as those of the “son of David” (Eccles. 1:1), and the speaker later describes himself as having been “king over Israel in Jerusalem” (Eccles. 1:12). Only Solomon was both. Yet biblical scholars convincingly argue that the book most likely dates from the Hellenistic period, when Israelite religion first encountered the Greek notion of philosophy.

This context is reflected not only in the language of the book but in its form and the character’s behavior. Kohelet, though identified as a king, is likely not a name but a title that means “preacher” or “speaker in the assembly.” Kohelet’s action in speaking is consistent with his being the kind of itinerant teacher familiar from the Greek world. The form of his teaching, moreover, is self-reflective and questioning in a Socratic mode. As Elias Bickerman pointed out in his classic work, Four Strange Books of the Bible, one of the peculiarities of Ecclesiastes is that the speaker so consistently and emphatically uses the first-person pronoun ani—speaking, as it were, in soliloquy, rather than with confident impersonality about the nature of reality that was the norm for wisdom literature. What that ani appears to be doing, meanwhile, is philosophy: stating a belief, testing whether it is true, and rejecting those beliefs that are contradicted in favor of a more purified understanding.

Ecclesiastes, then, is a record of Kohelet’s philosophical investigations in dialogue with himself. But on closer inspection, the book is not so much a work of philosophy as a first-person account of the failure of philosophy. Kohelet is an individual striving to make some sense out of his life, only to discover that he cannot do this by philosophical means.

Far from a dispassionate investigation of the nature of reality, Ecclesiastesbegins in anguish, with Kohelet’s exclamation, “hevel hevalim hakol havel,” which the Geneva Bible renders as “vanity of vanities, all is vanity” (Eccles. 1:2). He goes on to declaim the pointlessness of action, or even of trying to explain the world, for twelve verses before settling down to tell us that his project was to do precisely that: “I have given mine heart to search and find out wisdom by all things that are done under the heaven” (Eccles. 1:13). He then immediately denounces this project as a “sore travail,” stating that even “in the multitude of wisdom is much grief: and he that increaseth knowledge, increaseth sorrow” (Eccles. 1:18).

It’s important to note that Kohelet frames his project in the past tense. When the book begins, he has already set out to find wisdom and found it wanting. He has already proceeded to try being a kind of Epicurean—“I said in mine heart, Go to now, I will prove thee with joy: therefore take thou pleasure in pleasant things” (Eccles. 2:1)—only to find this wanting as well. Neither the passing pleasures of wine, women, and song nor the enduring monuments of wealth, gardens, and grand edifices provided any lasting satisfaction. He has learned all this before he begins to write, and it is in that context that he drops his contradictory pearls of wisdom: that it is better to be stillborn than to live a long life with wealth and a hundred children and still be unsatisfied (Eccles. 6:3), yet somehow also better to be a live dog than a dead lion, since any kind of life is preferable to the nothingness of death (Eccles. 9:4–5).

The key word used in Ecclesiastes to describe reality is hevel, which the Geneva Bible translates as “vanity,” but a more literal translation is “vapor.” Vapor suggests insubstantiality and evanescence, which make sense in the context of Kohelet’s distress about the nature of things, but most fundamentally, vapor cannot be grasped. It has no form that can be traced, no path that can be predicted—it is, in the modern scientific sense, chaotic. Kohelet’s opening declaration, then, is a forthright admission of failure: I set out to comprehend reality using reason, and I could not. Kohelet is left with no clear sense of what to do or how to live. The capstone to his moving meditation in chapter 3 on how everything has its particular season decreed by God is: “What profit hath he that worketh of the thing wherein he travaileth?” (Eccles. 3:9). We mortals cannot even know what season it is, and therefore, cannot take the action appropriate to the time.

Hamlet begins in a remarkably similar place to Kohelet. His first soliloquy—before the Ghost has appeared, before he has any intimation that his father was murdered—is thoroughly disordered, a mass of sentence fragments and self-interruptions, uttered by a man in the deepest throes of distress:

O, that this too, too sallied flesh would melt,

Thaw, and resolve itself into a dew. (Hamlet, 1.2.129–130)

Hamlet’s first wish when he speaks to us in solitude is to be dissolved into formlessness—a sense magnified in the Folio version, which replaces the second Quarto’s “sallied,” meaning assailed (or possibly a typesetter error for “sullied”), with “solid.” Why does Hamlet want to melt, to evaporate? His own words tell us that the world itself has come to seem formless and disordered on account of his mother’s hasty and incestuous remarriage to his uncle, but lurking behind this is something else. Hamlet is a student in Wittenberg, famous as the town where Martin Luther was a monk and as the home of Dr. Faustus, the alchemist and magician memorialized by Christopher Marlowe as a man who made a deal with the devil for knowledge and power. Hamlet is not just anyone facing a crisis of succession or confronting the fact of his mother’s enduring sexuality. He is an intellectual primed to seek understanding independent of received wisdom or tradition, as an individually discernible truth.

What are the alternatives to wisdom or tradition? One answer is revelation—and this is just what the Ghost appears to provide, supernatural confirmation of his worst opinion of his uncle and a command to take vengeance. Hamlet’s immediate impulse when the Ghost departs is indeed to take its commands as a rejection of traditional wisdom:

Yea, from the table of my memory

I’ll wipe away all trivial fond records,

All saws of books, all forms, all pressures past

That youth and observation copied there

And thy commandment all alone shall live

Within the book and volume of my brain

Unmixed with baser matter. (Hamlet,1.5.98–104)

Revelation—the Ghost’s revelation—has, Hamlet says, supplanted wisdom, for what good is wisdom to a revenger? Yet within a few lines, he’s taking notes again—“My tables! Meet it is I set it down” (Hamlet, 1.5.107)—and when the “perturbed spirit” of the Ghost has finally come to rest, Hamlet bewails the very command for revenge that should give purpose to his being:

The time is out of joint. O cursèd spite,

That ever I was born to set it right! (Hamlet, 1.5.186–187)

This is the spirit in which Hamlet proceeds through the next four acts: avoiding the mission of vengeance he is charged with by his father’s spirit and then wondering at his own inaction. That same wonder has obsessed critics for centuries and famously provided Freud with the basis of a diagnosis: that Hamlet cannot kill his uncle because Claudius has fulfilled his own Oedipal dream of murdering his father and marrying his mother. But it is worth taking Hamlet at his word about why he cannot simply take vengeance as he is commanded: because when he thinks about it, the Ghost’s command may be as insubstantial as the Ghost is itself.

In his third soliloquy, the first after the shock of the Ghost’s appearance has worn off, Hamlet debates the reliability of the Ghost’s testimony. The spirit may be only pretending to be his father, for the devil has the power to “assume a pleasing shape” (Hamlet, 2.2.535). The word “pleasing” is chosen advisedly; it is precisely because the Ghost tells Hamlet just what he wants to hear that he quite rationally suspects it. There is also a religious component to his skepticism; as many critics have noted, it’s odd that the Ghost declares himself to have come from purgatory since purgatory was a Catholic concept officially denied in Protestant England. Does his stated origin then prove him to be an evil spirit and not the ghost of Hamlet’s father at all?

For all these reasons, Hamlet looks for other proof—hence the play within a play that Hamlet stages to “catch the conscience of the king” (Hamlet, 2.2.540). But as John D. Cox points out in his book Seeming Knowledge: Shakespeare and Skeptical Faith, the play does not prove what Hamlet wishes it would. The staged imputation that the king murdered his brother for the crown would be politically explosive even if the charge were false. Moreover, all of Claudius’s earlier actions are consistent with a genuine concern for his nephew and a determination to have him succeed him, and all his actions thereafter are consistent with fears of the threat an increasingly mad Hamlet poses to him. The only reason we in the audience know Hamlet’s cause is just is Claudius’s confession in act 3, scene 3—which Hamlet does not hear. Had we not heard it either, we might well wonder with Hamlet whether the Ghost spoke truly; had we not heard the Ghost, we might well wonder if Hamlet had in fact gone stark mad.

Because we have heard the confession, we in the audience have a godlike view; we know what season it is and what the time’s purpose might be. Hamlet knows less, knows that he knows less, and therefore cannot act. But Shakespeare may be tricking us with the very knowledge he bestows. After all, as a Christian, one thing Hamlet does know is that vengeance belongs to God. Why, then, should Hamlet take vengeance at the Ghost’s command? Every word the Ghost spoke might be true—as we in the audience know it to be—yet it might still be an evil spirit tempting the prince into murder and regicide.

I think it’s worth taking this possibility at face value. Hamlet is not only the hero of a revenge tragedy; he’s also the object of a revenger—and so was King Hamlet before him. Hamlet recognizes that Laertes’s thirst for vengeance against him (for killing his father, Polonius), is as valid as his own claim as a son against Claudius—“For by the image of my cause I see / The portraiture of his” (Hamlet, 5.2.77–78 in the Folio edition). But Shakespeare embeds Hamlet’s tragedy within yet a third revenge plot—of young Fortinbras seeking vengeance for his father’s death at the hands of old King Hamlet. How much moral force can we accord the cry of revenge from a Ghost who, were he living, would himself have been a target of a revenger’s fury?

Truly, there is nothing new under the sun. These concentric circles of vengeance drive home the absurdity of Hamlet’s mission and explain his inability to act. Much as Kohelet persistently equivocates between life and death and cannot find a solid ground even for basic self-interest, Hamlet cannot help but equivocate over whether his own life is worth preserving or his mission of vengeance worth pursuing. It is not accidental that Hamlet’s most famous soliloquy persistently blurs the rhetorical line between suicide and revenge, both being ways “to take arms against a sea of troubles / And, by opposing, end them” (Hamlet, 3.1.58–59). The structure of a revenge tragedy compels us to urge on the revenger, but this is not a moral impulse: it is a perversion of it—and both Hamlet and Hamlet seem to see this.

Ecclesiastes appears to offer no similar family backstory for making sense of Kohelet’s misery as Freud’s family romance provides for Hamlet—but if we take the traditional notion that Kohelet is Solomon seriously, comparisons suddenly spring forth. Solomon, after all, was witness to an almost absurdly on-point Oedipal struggle within his own family when his half-brother, Absalom, revolted against their common father, David, and slept with David’s concubines as a way of fortifying his claim to the throne. David’s deathbed advice to Solomon was to kill the man responsible for Absalom’s death, his commander, Joab. Solomon also had to commit fratricide to consolidate his power, killing Adonijah, his half-brother, who had himself crowned king first. Solomon’s struggle for the throne was fully as bloody and incestuous as the one in Elsinore, but he played the royal part that Hamlet labors to avoid.

A suggestion of Rashi provides an even more valuable interpretive lens onto the personal drama behind Kohelet’s melancholy. His commentary suggests that King Solomon foresaw the division of the kingdom under his son Rehoboam and that this was the source of Kohelet’s despair. It’s a notion that can be used to bring many of the book’s apparent contradictions into sudden focus. Why, for example, is Kohelet so persistently concerned with the possibility that someone unworthy will enjoy his wealth? With the possibility that his heirs will be fools? One verse can stand for many others (here in the modern JPS translation):

For sometimes a person whose fortune was made with wisdom, knowledge, and skill must hand it on to the portion of somebody who did not toil for it. That too is futile [hevel], and a grave evil. (Eccles. 2:21)

Now imagine Kohelet/Solomon realizing that his heir would almost certainly squander what he had labored so hard for—and not only that, but his own “wisdom” had led him to kill Adonijah to secure a kingdom that might last only a generation. Is it any wonder that such a man would despair?

Furthermore, who is Kohelet speaking to throughout the book? Wisdom literature was conventionally addressed to young men of promise. Polonius’s speech to Laertes is an excellent example of the genre, full of wise advice on how properly to “seem” to get along in society (before ultimately contradicting itself with an admonition to be true to oneself above all). For much of Ecclesiastes, Kohelet seems to be talking to himself, brooding on the futility of his own search for wisdom and his efforts in the world. Yet when he breaks from this mode and actually gives advice, his imagined audience seems to be one of those youths—one who requires a particularly chiding form of wisdom. If we identify Kohelet with Solomon, we can readily imagine who his audience is. “Be not rash with thy mouth, nor let thine heart be hasty to utter a thing before God” (Eccles. 5:1) and “Better it is to hear the rebuke of a wise man, than that a man should hear the song of fools” (Eccles. 7:2 in the Geneva edition) are apt barbs to sling at Rehoboam.

From this perspective, the book suddenly ceases to be formless and self-contradictory and takes on literary shape. It begins in despair at the futility of any effort to acquire wisdom or leave a legacy, since one’s foolish heirs will squander it, and anyway, you won’t be around to enjoy it if they don’t. It proceeds to a bitter kind of wisdom that warns those heirs not only against their folly but against ambitions of all kinds, even against the joys of life, contradicting the lesson the speaker seemed to take from his own life misspent (as he sees it) in ambitious toil. Finally, it concludes with an empathetic reconciliation with the need to live and enjoy one’s lot in life—even if one is a wastrel fool like Rehoboam—before the inevitable bodily and societal decay. That decay is hauntingly described in the poetry of chapter 12, “When the keepers of the house shall tremble, and the strong men shall bow themselves, and the grinders shall cease, because they are few, and they wax dark that look out by the windows” (Eccles. 12:3).

Rehoboam himself is not a character in his own right; Ecclesiastes is an interior dialogue, and there is no sense that anyone has heard it but the author of the book, who, Horatio-like, pens the last lines of chapter 12 in his own voice and puts a pious gloss on Kohelet’s despair (“Let us hear the end of all: fear God and keep his commandments: for this is the whole duty of man.For God will bring every work unto judgment, with every secret thing, whether it be good or evil,” Eccles. 12:13–14). But there may be another reason why Rehoboam cannot hear Kohelet’s warnings. When Kohelet introduces himself, it is in the past tense—he was king. But Solomon reigned until his death. If we are to take this retrospective stance seriously, then perhaps Kohelet is himself a ghostly speaker from the undiscovered country beyond the grave, more like the elder Hamlet who had been king than the feckless son who never was.

One may ask how Ecclesiastes, a book that questions traditional wisdom literature and at least flirts with Epicureanism, came to be included in the Bible, and many have. For me, the more interesting question is less how the book came to be canonical than how it came to be composed. Once again, Hamlet suggests a fruitful way to think about the question.

The Hamlet we know is not the original. Shakespeare usually worked from preexisting material, and in this case, there was an earlier play (possibly his own, more likely by Thomas Kyd) with the same central character and a ghost crying, “Hamlet, revenge!”—which we know because contemporary audiences mocked it for precisely those elements. We don’t know why Shakespeare set out to revise this so-called ur-Hamlet, but the critic William Empson made an insightful suggestion about how the decision to do so led to a play of such depth.

The essential problem of the revenge tragedy is its predictability: we know that the revenger will get his revenge, and much of the play consists of tactics to delay the inevitable end. Once audiences understood the genre, it was too easily parodied; the problem for Shakespeare was how to make the old formula work again for audiences who had grown wise. So, Empson suggests, Shakespeare chose to hide his problem in plain sight: he made his main character self-conscious, aware of the absurdity of being a character in a revenge tragedy and aware that his delaying tactics made no sense given the role he was fated to play. Thus Shakespeare’s solution to a formal problem created a new Hamlet who was so complex and conflicted that he became one of the greatest characters in Western literature.

I imagine something similar could have been true of the writing of Ecclesiastes. Picture the author as an Israelite who was at least passingly familiar with Hellenistic thought—with the Epicureans, Stoics, and other philosophical schools—who set out to write a work of wisdom literature informed by their method. He even hit upon the brilliant idea of speaking through the legendarily wise King Solomon. Yet quickly, he thought himself into a cul-de-sac: if wisdom governed the universe, that meant that reality could be apprehended and laws divined that could be followed for our good. But when he examined the world, this was not what he saw, and the more he applied the tools of reason, the more understanding slipped from his grasp. His whole project seemed absurd and pointless.

So he imbued his preacher with consciousness of that very absurdity and thereby made all other wisdom literature—books like Proverbs (also ascribed to Solomon by tradition)—seem stuffy and obsolete, Polonius-like by comparison. His Kohelet became the aged Solomon—or perhaps even his ghost—who surveyed his life of apparently transcendent accomplishment—he built the Temple in Jerusalem!—and found even that to be striving after wind.

Where does that kind of wisdom leave the faithful reader? The author’s concluding words in his own voice offer only an anxious shelter in conventional piety: God’s commands apply to everyone, the wise and foolish, the rich and the poor alike, and do not require that one understand the universe to follow them. Piety is less a path to success than a path out of paralysis; at least you know what to do. I suspect Hamlet would make quick work of such a conclusion. Kohelet’s own last words, though, are a haunting poem that merges the decay of the physical body with the decay of a great estate with premonitions of the end of the world, ending with “and dust return to the earth as it was, and the spirit return to God that gave it” (Eccles. 12:7), to which Hamlet’s final “the rest is silence” would provide a fitting coda.

If one wants to locate Kohelet’s ultimate wisdom in Hamlet, I believe it can be best found in something Hamlet says to Horatio, the self-described “antique Roman” who seems to believe in the promise of philosophy. Explaining why he has accepted Laertes’s challenge to a fencing match even though he knows it’s probably a trap, Hamlet says:

There’s a special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be now, ’tis not to come. If it be not to come, it will be now. If it be not now, yet it will come—the readiness is all. Since no man of aught he leaves knows, what is’t to leave betimes. Let be. (Hamlet,5.2.197–202)

We can never truly know what purpose is prompted by the time in which we find ourselves. We can only be. Which, in the end, is a fitting meaning for a season when we are commanded to sit in a roofless shelter and joyfully pray for rain.

Suggested Reading

The Quality of Rachmones

Howard Jacobson's Shylock Is My Name is dead serious and very funny, high criticism and low comedy.

Sitting with Shylock on Yom Kippur

The poet Heinrich Heine imagined the merchant of Venice attending Neilah, the final service of Yom Kippur, but I find him earlier in the day, at Mincha, and we are listening together to the story of another Jew among Gentiles, bitter at being compelled to show mercy.

King James: The Harold Bloom Version

There may be a thousand facets to the Torah, but does Harold Bloom simply misunderstand the King James Bible?

A Dissonant Moses in Berlin and Paris

Schoenberg’s challenging opera is re-staged in 21st-century Europe.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In