Memories of Morocco

In 1948 about a quarter of all the Jews in the Middle East (including Turkey) lived in Morocco. Their experience, though distinctive, was neither wholly divergent nor wholly representative of Jewish life in the Islamic world. Consider just a few facts.

Until the early 1900s, Jews, as dhimmis, “protected People of the Book,” were subject to special taxes, expected to wear distinctive clothing, confined to separate urban quarters, and occasionally attacked. At the same time, they might share property with their Muslim neighbors, were asked by the Muslims to invoke God’s favor in times of distress (sometimes, as José Alberto Rodrigues da Silva Tavim notes in one of the many excellent essays in Jews and Muslims in Morocco: Their Intersecting Worlds, by praying together with them), and were most often subject to violence when other Moroccans were also being attacked—for instance, in the chaos after the death of a king.

For Moroccan Muslims, who often relied on ritual reversals to level power, it was common to regard Jews as inferior yet invite one of them to touch the plants in one’s garden when drought or disease threatened the crops. In rural areas Jewish traders received the zealous protection of Berber trading partners, who brought them gifts on the Jewish holidays. In many cities and towns, the shrines of Jewish saints were visited by Muslims who might even settle a dispute with an oath taken at one of those sites.

In the centuries before the imposition of the French protectorate in 1912 (the northern section of the country having been placed under the control of Spain, while Tangier was declared an international city), Jews were without any distinct role in the political system. Nevertheless, through the international connections of important families, in the offices of the occasional Jewish adviser or physician to the ruling sultan, or as a result of the monarch’s need to prove his legitimacy by his ability to protect the powerless, the Jews were at times able to seek royal favors to ameliorate their depressed condition. There were, however, some costs associated with having a small elite as the point of contact for the community as a whole. As Daniel J. Schroeter points out in his essay, vertical alliances with the ruler often came at the expense of horizontal ties within the local community.

At the local level, Jews often occupied distinctive occupational niches. A number were metalworkers and craftsmen, while others funded Muslim farmers in exchange for a share of their harvest. Metalworkers often doubled as plumbers because they could enter a Muslim’s house and see the women inside and the owner’s wealth without the fear that they would discuss them with other Muslims. In his personal account of growing up in the southern town of Taroudant, Joseph Chetrit, one of the editors of Jews and Muslims in Morocco, recounts how the Muslim clients of his seamstress mother “completely confided in her and even shared their family problems,” a practice many others have noted as well. As resident strangers, Jews could be told things not readily told to a fellow Muslim, thus forming a bond of intimate disclosure not unlike that of telling a stranger on a long trip things one might never tell one’s closest friends.

Among the Jews themselves, there were significant differences of background and orientation. One branch, the toshavim, whose members probably left Roman Palestine before the destruction of the Second Temple, spent centuries making their way across North Africa, even converting some of the Berber tribesmen along the way. A second, quite separate wave of some twenty thousand to thirty thousand souls occurred when the Jews were expelled from Spain and Portugal at the end of the fifteenth century. These migrants, the megorashim, were more cosmopolitan and tended to settle in such key cities as Fez and Marrakesh and the coastal trading centers. For all the similarity in their circumstances, the two groups of Jews nevertheless parted company on certain key matters of law and culture. For example, as Moche Amar points out, the megorashim brought with them inheritance laws affected by their experience in Iberia, a system that gave a substantial portion of a deceased wife’s estate to her own kinsmen, to the detriment of her husband and sons. The rabbis of the toshavim, by comparison, favored a system that secured sons’ inheritance, particularly if the mother remarried after the father’s death, a policy closer to that of the dominant Muslim population.

The approach to inheritance also underscores what might be regarded as a distinctively Moroccan approach to change and accommodation. As Melech Westreich notes in his essay:

Moroccan sages were acutely aware of the needs and hardships of the community, which motivated them, as a collective of scholars, to use the tool of legislation [halakha] without anxiety.

So, for example, they altered the traditional practice of metzitzah be-peh in circumcision, in which the mohelremoves blood from the circumcision wound through oral suctioning, when nineteenth-century science began to pronounce it unsafe (the custom is still common among contemporary Ashkenazi haredim in New York and elsewhere). Even more daringly, they “looked at reality with open eyes and coped with demands of the public to improve the situation of women” in such matters as divorce and levirate marriage. In the process, they developed not only a supple version of Jewish law but one that the Muslims were willing to allow the Jews to apply to their own internal affairs.

In speech and proverb, cuisine and music, Jews and Muslims were simultaneously distinct and deeply involved in mutual borrowing. This cultural symbiosis manifested itself in numerous ways. As Noam Sienna points out, Jewish concepts of the role of demons in human lives were not only influenced by Muslim beliefs but also demonstrated how much the reliance of each on the everyday beliefs of the other reflected a deeper interdependence. This theme is also extended by Sarah Frances Levin’s description of the Moroccan poetry duels, in which Berbers and Jews faced off in friendly competition that served to elicit community values and resolve minor disputes.

Folktales, too, reveal much about the Jews’ situation in Morocco.Some are fantasies of the weak, as when a minister of the king claims that a Jew is dangerously disloyal, only for the accused to appear before the monarch and insist that his powers are always in service of the throne. He convinces the king that he can prove it by hacking the minister to pieces and then reassembling him—at which point the minister, of course, retracts his charges. In another trickster tale, a Jew is ordered to prepare “some” chickpeas, but when the pot is shown to be empty, he demonstrates his cleverness by saying that he did as directed because he put in two peas, then ate the first to determine that they were not yet done and the second to confirm that they were. Such stories relied on the symbols and narratives that Moroccan Jews shared with their Muslim neighbors.

Much, of course, changed with the onset of the French protectorate in 1912. Unlike Algeria, where Jews were made French citizens in 1870, Moroccan Jews remained subjects of the sultan. But Jewish agencies, such as the Alliance Israélite Universelle, offered not only the opportunity for a Western education but a cultural attachment that went beyond the protégé status that some Jews had previously obtained from foreign governments to avoid local jurisdiction. Indeed, the French preferred that the Jews remain subordinate to the nominal Moroccan authorities out of concern over disturbing both Muslim and European residents. Yet the ambiguities of the Moroccan situation remained in play. This was particularly visible around the time of the Second World War.

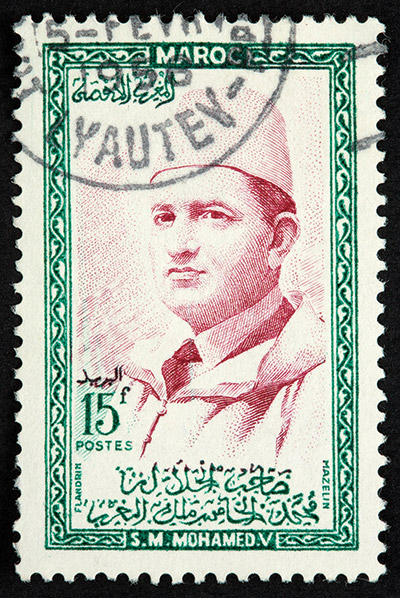

During the interwar years, France had been able to retain its hold on Morocco and even complete its “pacification” of the south. With the arrival of the Vichy regime, the Moroccan sultan, Mohammed V, tried to walk a fine line between having, on the one hand, to sign onto laws limiting the number of Jews in various professions and places of residence, and, on the other, making it clear to his new colonial overseers that he would protect the Jews from loss of property and personal harm. Although the story that he threatened to wear a yellow star if Jews were required to do so is almost certainly untrue, he did make efforts to ameliorate the impact of Vichy on Jewish Moroccans. This led Shimon Peres and others to push for Mohammed V to be recognized as one of the Righteous Among the Nations at Yad Vashem, though the initiative was not successful. As Joseph Chetrit notes, the sultan’s protection of the Jews as dhimmis coincided with the actions of those few but important French officials who acted as a shield against the Vichy forces and its local French supporters. The Jews, for their part. supported the sultan in perpetuating their historic dhimmi status, even sacrificing a bull at his doorstep in a traditional plea for protection.

The interwar years brought an exposure to modern French culture that put a strain on the internal dynamics of the Jewish communities, a strain that was only to increase in the years leading up to Moroccan independence in 1956. During this time the Jews divided into three main political groups: the traditionalists, the increasingly popular Zionists, and the Communists. While Mohammed V quietly nursed nationalist sentiments—leading to his forced exile from 1953 to 1955—rising nationalism was not the only event that affected the Jews’ choices.

With the founding of Israel in 1948, the loss of confidence in France as a protector, and concern about rising pan-Arabism, the Jews began to leave Morocco. By the time of independence, ninety thousand had emigrated. The sequence of their leaving was predominantly from the bottom of society up, the poorest heading for Israel, the wealthier for France and Canada. The sultan briefly banned the Jews’ departure in 1957, and, though he quickly relented, many departing Jews still had to sell their belongings for whatever they could get. When Mohammed V suddenly died after a minor operation in 1961, the flow of migrants only increased. In part as a result of the fears instilled by the Jewish Agency for Israel and Mossad, in part because of uncertainty about the new king, Hassan II, another ninety-two thousand departed by 1964.

At first it seemed as though the rule that “Jews don’t do politics” might change as the new Moroccan political parties held out the promise of communal inclusion. But as Alma Rachel Heckman points out in her comprehensive and fascinating new history of Jewish involvement in the Moroccan Communist Party, The Sultan’s Communists: Moroccan Jews and the Politics of Belonging, the ambiguities of the Jews’ position carried over into the postindependence period. In the king’s first cabinet, for example, there was a Jewish minister, while a number of others were appointed at lower levels. The main nationalist party, Istiqlal, appeared to welcome Jewish participation through its formation of the al-Wafiq (Accord) group, which urged the country not to conflate Zionism with Moroccan Jewishness. However, the party’s leader, Allal al-Fassi, also spoke of “the perfidious role that Jews played at the beginning of Islam” and declared that “Jewish Moroccans are nothing but dhimmis.” For those who chose neither to depart for Israel nor embrace their traditional second-class status, there was the alternative of the Communist Party.

But here, too, the ambiguities could not be finessed. As Heckman points out, most Jews rejected the anti-Zionist position of the Communist Party and wanted little to do with those Jews who joined it. Nor was the government entirely comfortable with the party: fearful that the Communists would turn on the monarchy, Hassan II did not hesitate to imprison and torture those whom he regarded as threatening.

Jewish communists—most notably Abraham Serfaty, Simon Levy, Sion Assidou, and Edmond El Maleh—were incarcerated for lengthy periods in dismal conditions. They tried to insist that being a Jewish Moroccan was not a contradiction in terms, but their ardent opposition to the European colonialists and support for Moroccan nationhood was not enough to ensure their political inclusion. In a sense, instead of embracing the ambiguities of their situation, they fell victim to the rather un-Moroccan temptation of single-minded ideology. That all were rehabilitated late in life underscores the saying of Mohammed V that governing Morocco is like having a lion on a leash: sometimes you ease the pressure, and sometimes you have to reign it in tight.

Only 2,500 Jews remain in Morocco today, almost all of them gathered in Casablanca. Yet their felt presence lingers in ways that continue to reflect the enduring ambivalence of their position in the nation’s history and imagination. Muslim caretakers tend the cemeteries of the departed Jews, some of them having learned the Hebrew prayers and even how to restore Hebrew lettering on the worn headstones. With the strong support of the present king, Mohammed VI, many synagogues have also been restored. The revised constitution now states that the kingdom has been “nourished and enriched by its African, Andalusian, Hebraic, and Mediterranean influences” and speaks of the country’s “openness, moderation, tolerance, dialogue and mutual understanding between all the human cultures and civilizations.”

Before the pandemic, more than fifty thousand Israelis (and many other Jews of Moroccan extraction from France and elsewhere) visited Morocco each year, some even bowing to kiss the ground of their ancestors upon arrival. Celebrations at the site of Jewish saints are common, and a few of the saints’ remains have even been removed to Israel, where the associated hillula celebrations have become national events. Scholarship on Jewish history has also flourished, with a number of Moroccan Muslim scholars devoting their careers to the subject, among them such insightful writers as Mohammed Kenbib, Aomar Boum, and Abdellah Ouzitane.

Perhaps most poignant are the regrets expressed by many Muslims about the departure of the Jews. In a typical statement, one Muslim is quoted as saying: “We preferred to have Jews as neighbors rather than others. With the Jewish families as neighbors we felt more secure and at peace. Now that they are gone, all good things are gone with them.” Some houses of departed Jews have been reportedly left unoccupied in the hope that they will return. In Sefrou, a city in Central Morocco, I was once told that not only has economic trust vanished, but even the water in the river (known as the Oued el-Yahudi) had diminished since the Jews departed.

After his visit to Morocco in 1832, the artist Eugène Delacroix wondered: “Why, and despite their subjugation, do Jews live in good relations with the Moors?” But what may have appeared incongruous to a European observer may not have felt so for the Moroccan Jews. That Jews stood outside the traditional process of social reciprocity—that they were not going to seek the Muslim’s daughter in marriage for a favor done in the marketplace or bargain over one’s vote in the wake of help as an intermediary—meant that a relation of intimacy, indeed, of trust, was possible. Perhaps, then, it is not so strange that Moroccan Jewish singers remain enormously popular in Morocco or that memory, and not just nostalgia, are carried along in their shared cultural forms.

In Arabic, an occurrence will be categorized as long ago or recent depending not on chronology but on whether it continues to affect current relationships. It is in this sense that the Jews remain an “absent present” for Moroccan Muslims. They are so for its kings who must prove their legitimacy by protecting the powerless, even if it is only through the symbolic preservation of abandoned graveyards and houses of worship. And for ordinary Moroccans—at least for those who knew their Jewish neighbors well—the loss continues to occupy a key place in the collective imagination.

It was François Mauriac who said: “How distorted in our minds the people we know best become when we are not actually with them.” Indeed, it may be easier for both Muslims and Jews to embrace their attachments when they no longer are compelled to live together. And yet, there was a time when both had learned how to live in ambiguity. Perhaps the poet Mahmoud Darwish is right when he says that Jews and Muslims are destined “to live and dwell in the same metaphor.” Whether this interdependence can survive into another generation remains the shared uncertainty and the poignant challenge that, separately and together, both Muslims and Jews in the Middle East now face.

Suggested Reading

Victim Enough? The Jews of North Africa During the Holocaust

As the Tunisian Jewish novelist Albert Memmi wrote, “I am not enough of a victim; that is why my conscience is tortured.” Must the Jews of North Africa, as contributor Lia Brozgal puts it, write “a history that competes with a more catastrophic one, or be written out of history?”

Homer of Lod: The Indispensability of Erez Bitton

The blind writer from Algeria is one of Israel’s most important voices, both in poetry and in policy.

Crazy Rich Sephardim

For a time, Shanghai soared along with these unusual Ottoman Jewish émigrés, the Sassoons and the Kadoories.

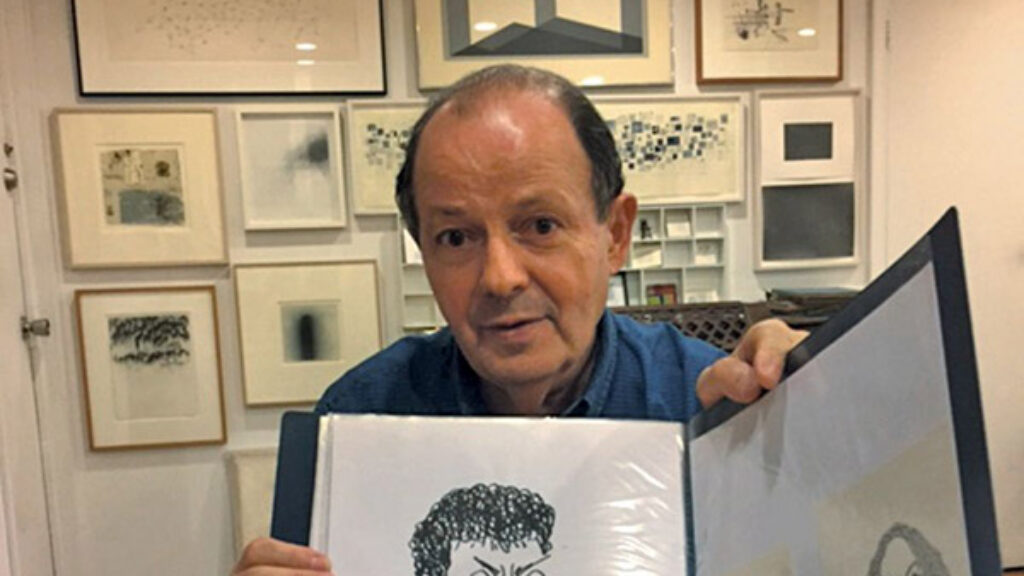

Time and Ink: The Minimalist Devotions of Jacob El Hanani

The idea of a scribe who, like El Hanani, sets to work every day but never produces the same text twice—or never produces a legible text at all—would have appealed to Franz Kafka.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In