Walking with Walter Benjamin

Ten minutes of walking, one minute of rest. Ten minutes of walking, one minute of rest. This was how Walter Benjamin made the hike over the Pyrenees from Banyuls-sur-Mer, France, to Portbou, Spain, in an attempt to flee Nazi-occupied Europe in September 1940. The hike takes most people six to ten hours to complete. It took Benjamin two days.

His guide, the resistance fighter Lisa Fittko, nicknamed him “Old Benjamin” because of his poor health despite his young age. His friend Hannah Arendt called him “the hunchback” after a German children’s poem, which he recalled at the end of his collection of autobiographical fragments Berlin Childhood around 1900, as he anticipated death. He suffered from asthma, was never suited for strenuous physical activity, and at age forty-eight had already suffered a heart attack.

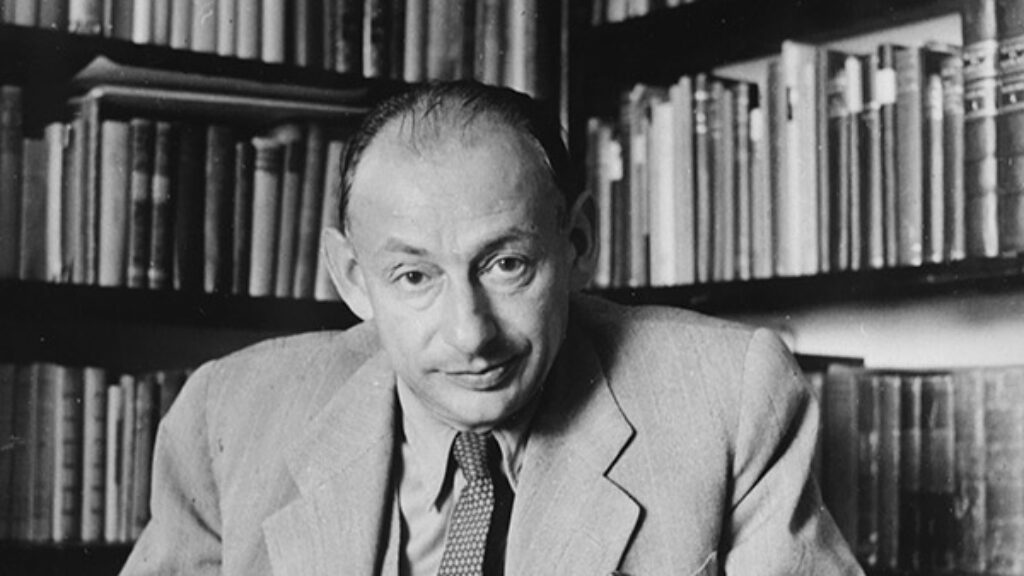

Benjamin never received much public attention during his lifetime, but fate has smiled on him posthumously, bestowing his life and work with a kind of fame reserved only for the greatest thinkers. He is now recognized as one of the most enduring cultural critics of the twentieth century for his prescient writing on technology, art, and cities. In his only finished monograph, The Origin of German Tragic Drama, he collected more than four hundred quotations from sixteenth- and seventeenth-century German playwrights, Shakespeare, and Caldéron to critique Aristotle’s definition of tragedy while taking aim at the fascist legal philosopher Carl Schmitt. It was rejected by his habilitation committee at the University of Frankfurt, thwarting the possibility of an academic career. Within a few years, it was being taught as part of the university’s curriculum. Benjamin’s all-too-short life, and long posthumous reception, is punctuated by such ironies.

And there is irony, too, in the fact that Portbou, where he tragically took his life the night he crossed the Pyrenees, has been turned into a Benjamin–themed tourist town. It was Benjamin who was among the first to understand what is lost when a cultural object, landmark, or work of art is transformed into an object of consumption. “Even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element,” he wrote, “its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be.”

The facts of Benjamin’s death in Portbou remain a mystery. We will never know precisely where he is buried or what date he died on. The Spanish doctor’s death certificate says September 26, 1940, but Henny Gurland, one of Benjamin’s companions on the hike, said that she discovered his body on September 27. Another burial record lists September 28, 1940, as the date of his death. And we will never know what was in his black leather attaché case, what final manuscripts he held onto for dear life and refused to part with on the difficult journey. Fittko reported that Benjamin told her they were his “most valuable manuscripts.” Was it a part of his “Arcades Project” (Passagenwerk), a collection of fragments of Paris in the nineteenth century? Was it further work on Baudelaire? Or was it, perhaps, a revision of his “Theses on the Philosophy of History”?

In September 2021, I went to see the Israeli sculptor Dani Karavan’s memorial for Walter Benjamin in Portbou and decided to return in the spring to follow Benjamin’s passage over the Pyrenees and retrace his final steps. Karavan’s memorial, aptly titled Passages, stands at the entrance to the cemetery where Benjamin was (supposedly) buried in a pauper’s grave on the edge of a cliff overlooking a small cove that leads out to the Mediterranean Sea. The work is an invitation, appearing like an open door when you approach it, then revealing a steep and narrow staircase leading down to a pane of glass, which is all that separates you from falling into the sea.

Passing through the memorial’s rusted steel frame, the walls echoed as I descended the eighty-seven stairs. For a moment, it was as if I were entering a mikvah, and the world above was somehow now separated from the world below. Something was being left behind, but no submersion was possible. When I reached the bottom, I read the passage from “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” which had been etched into a plate there:

It is a more arduous task to honour the memory of anonymous beings than that of famous persons. The construction of history is consecrated to the memory of those who have no name.

I sat on the stairs, closed my eyes, and prayed. Somehow leaving the memorial made me feel as though I was leaving Benjamin on the threshold between death and freedom, and I didn’t want to go. Karavan said of his memorial, “Here nature tells the tragedy of this man. Nobody could present it better. All that remains to be done is to bring the pilgrim to see what nature says.”

The Pyrenees are famous for their unpredictability. The wind comes out of nowhere, pushing you down. I had to extend my hotel reservation in Banyuls for two days because the wind was blowing in too strongly from the sea to make the hike. The woman at the tourist center advised just waiting another day or two, she couldn’t say for sure. The mountain terrain is rough. There are long stretches where one is left to scramble over rocks without a path along the edge of a cliff. And even with the occasional hash marks on weather-worn stones and trees, which assure you that you are still on the route, there are long stretches where one does not see them at all.

The trail begins in the middle of Banyuls. There are bleached yellow one-way street signs marking the way through the town that read, “Chemin Walter Benjamin.” The town feels as though it still belongs to that part of the nineteenth century when people escaped to the sea for rest and relaxation. To one side there is a small footbridge leading to the highway, to the other vineyards and the stony green face of the Pyrenees. I followed the signs as I left Banyuls through an apartment complex, a cul-de-sac neighborhood, across a bridge and creek, to a road where a sign was pointing the way down a narrow staircase into the woods. A small girl was riding her bike in circles along the road. At the bottom the landscape opened onto rolling hills of vineyards growing grenache and Syrah grapes, still unripe in springtime.

After almost two hours of walking through the vineyards, I reached the start of the trailhead where another sign said, “This is the track Walter Benjamin took to head to Spain as he was running away from Nazism.” On the bottom of the sign someone had written in fat blue marker, “NO BORDERS, NO NATIONS. FIGHT FASCISM EVERYWHERE!” Stepping up through the vines, the path narrowed. Instead of an open winding road, there was only a narrow path of loose rocks leading straight up into the mountains, with little visibility ahead.

When Benjamin made his desperate hike, he had been caught in the dizzying storm of statelessness, without his library, papers or a real home he could return to, for seven years. He wandered between friends, visiting Bertolt Brecht in Denmark and the Adornos in San Remo, Italy, and spending time in his small Paris apartment with Gershom Scholem. He was a collector who traded in allegory and used metaphors to transform the mundane objects of everyday life, like a bowl of borscht, into experiences that could transport the reader, awakening the senses and illuminating the world.

In One-Way Street he wrote, “In a dream, I saw a barren terrain. It was the marketplace at Weimar. Excavations were in progress. I, too, scraped about in the sand.” He knew the country of his childhood was gone. The streets of old Berlin, where he had had his sexual awakening while rushing to synagogue on Rosh Hashanah, had disappeared for him. And in their absence, he fixed his attention on the things that carried the past with them into the present.

I stopped at a turn in the path and looked behind me. I could barely see the narrow footbridge I had crossed a few hours ago; Banyuls was already so far away. Alone in the vineyards, hiking up these narrow paths, what does the collector’s eye see? What does one hear? The green hills, the yellow flowers, the rocks, the sea? Or the music of a Sunday sitting room, with bowls of overripe fruit, broken open in the sun?

Benjamin did not want to go to America. He told Arendt that they’d probably drag him up and down the East Coast as the last European. He was afraid he himself would become an object of novelty, a relic of a world disappeared through war. His meticulous collection of children’s books were gone, his puppet theater, his radio show, the streets of Paris he had written about conquered by the Nazis. Benjamin said it wasn’t so much the possession of the objects by the collector as it was the way the owner was in the objects he collected. The losses he had endured were already unbearable.

After continuing for some way up another vertical ascent, I reached a turn around a steep cliff, revealing a valley to my right. Resting against the side of the mountain, I could see the vineyards of Banyuls shrunk in the distance, and beyond them the sea. I perched my feet against the twisting roots of a tree trunk and gathered strength to climb around the rocks and boulders to the other side. I had no idea where I was in the hike at this point. As I scrambled around the rocks, the path opened onto another road, and I exhaled a sigh of relief. There was a tall electrical tower on which someone had written, “It’s the path of Walter Benjamin.”

Fitko had set out with the group a day early to scout the path. It was her first time making the crossing with others. She had a small hand-drawn map with some markers on the route. When they reached a clearing next to a boulder about a third of the way up, she decided that they had to turn back. But to Fittko’s consternation, Benjamin refused to return to Banyuls with the group. He was exhausted and afraid he wouldn’t be able to go back down and up again, so he spent the night alone on the mountain. As Fittko described it:

We were in a wild mountain region—perhaps there were dangerous animals. I actually had been warned that there were savage bulls hereabouts. It was late September and Benjamin had nothing to cover himself with. Smugglers roamed around the area—who knows whether they might do something to him? And he had no provisions whatsoever. No, it was really an impossible idea.

When I reached the clearing, there was another sign. “On the way to Spain, the group Walter Benjamin was part of had a rest near the spring.” The light cut through the trees. The generous space around the natural rock formation offered shelter from the midday sun and enough room to stretch out for a while. I set down my pack and wondered what Benjamin thought about during his night on the mountain. He had been suffering in exile for years. Was he like Jacob alone in the wilderness, wrestling with an angel until dawn?

In The Arcades Project, Benjamin describes three figures: the gambler who passes time, the

flâneur, or urban wanderer, who stores time, and the one who waits, transforming time into excruciating anticipation. Unlike his long rambles through the Paris Arcades, or his drunken meanderings over the green hills of Ibiza, he was now forced to wait in the wilderness not knowing what to expect. In his last letter to Theodor Adorno sent just a few weeks earlier, he had written, “The complete uncertainty about what the next day, even the next hour, may bring has dominated my life for weeks now.”

The next day Fittko returned with the others, and together they walked on toward the Spanish border. I put on some sunscreen and continued on. There is no reprieve between the resting place and the summit. The route narrows again, and soon I was on the most difficult part of the trek, without much of a path, making the vertical ascent. As I scrambled on my hands and feet over boulders and loose rocks, trying not to fall with little visibility ahead of me, I thought about Benjamin’s patience: ten minutes of walking, one minute of rest. Finally, I reached the first border fence in a clearing. I unlatched the metal gate and walked into the Catalan region of Spain, Portbou visible for the first time in the distance.

But it was not the summit. Soon I reached a steep pass, a broken tooth piercing the sky, and my heart dropped. It was a nearly vertical rock scramble over the mountain. As I made the summit and began the descent, the trail disappeared almost entirely. I had to blur my vision to not overthink where I was stepping, following the faintest trace of others who had gone before me. When I finally reached a clearing, I could see Portbou again. I was exhausted, hungry, and almost out of water. I sat down knowing there was more than an hour left and cried.

Sometimes the weight of not knowing the future is too much, and it’s not despair that conquers the spirit but quiet resignation. I thought about Heinrich Blücher’s letter to Hannah Arendt from inside the internment camp and how he described Benjamin as being despondent, sitting upright all day on a bench, unable to speak or move. His composure, bordering on comatose, made him appear like an apparition to the other prisoners. It’s not difficult to imagine him as you move along the rugged terrain, hiking up the mountain in oxford loafers, with his leather attaché case in his hands, holding onto his manuscripts for dear life. I found myself wondering if he had used the briefcase to steady himself against the rocks.

As I made the final trek, I felt the pull of hope and tug of despair as Portbou appeared and disappeared with each turn in the road. One minute it was so close; the next it wasn’t visible at all. After what felt like eternity, I reached the end of the trail, and the wilderness gave way to a road and the now-abandoned border station. I slipped between two long hairpin gates installed to prevent cars from crossing and saw a sign marking the end of the trail.

Walking down into Portbou, there is a sign that reads, “Walter Benjamin is Detained.” It offers visitors a walking map of Portbou tracing Benjamin’s final footsteps, from the train station, to the town square, to the Hotel de Francia where he died, to Dani Karavan’s memorial near the cemetery.

When Benjamin reached Portbou, the Spanish government refused to grant him safe crossing, and he faced another night alone. This time he was in a hotel room, down a cobblestone street, up a small flight of stairs, somewhere between France and Spain, with nothing more than his most treasured manuscripts. He had devoted so much of his writing life to Paris and Berlin—and now he was stranded alone in a village in the Pyrenees mountains. And on this night, whatever was in that suitcase wasn’t enough to deliver him safely to morning.

If he had left one day earlier, or one day later, the Spanish border guards would have let him pass, but some new bureaucratic measure—quickly erased—was now in effect. It was a final, brutal twist of fate. Unable to face making the crossing again, he wrote his final letter:

In a situation with no way out, I have no other choice. My life will end in a little village in the Pyrenees where nobody knows me. I ask you to pass on my thoughts to my friend Adorno and to explain the position I found myself in. I do not have enough time to write all the letters I would have liked to write.

These words are now inscribed on a rusted steel post in the cemetery overlooking the sea, only visible in the noonday sun.

I walked through town and watched the sun set from Karavan’s memorial. A cool band of green light spread out across the horizon as the water churned below, revealing shades of blue. As sunset faded to night, I thought about Benjamin’s gambler, suddenly returned by the morning light to the world from the darkness of the casino. I thought about his flâneur, lost in the crowd, wandering aimlessly through winding city streets, undone by the maddening movement of bodies. And I thought about the one who waits—standing on the other side of the door—hoping with each breath that somebody will knock to deliver him from another night alone.

After some time, I turned away from the sea and walked to my hotel room.

Suggested Reading

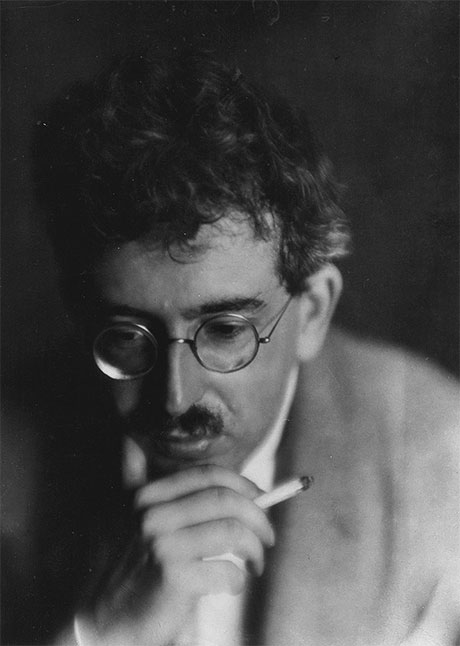

Between Frankfurt and Jerusalem: Scholem, Adorno, and the Fate of the Sacred

When the philosopher Theodor Adorno met Gershom Scholem, he thought that he “gave the impression of a Bedouin prince.” Their lifetime of letters orbits their shared love of their brilliant, doomed friend Walter Benjamin.

Remembering the Scholems

New books about Gershom Scholem and his brother Werner evoke memories of 28 Abarbanel Street in Jerusalem.

New Thinkers, Old Stereotypes

Moshe Idel is heavy on melancholy, not to mention surprising claims about the scholars of Western Europe.

Graven Images

“How do you like my drawing?” Franz Kafka wrote his fiancée Felice Bauer. He took art seriously, and now, finally, we can answer the question ourselves.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In