Letters, Spring 2019

Lachrymose Criticism?

Dara Horn’s review of Black Honey, a film dedicated to the poet Avraham Sutzkever (“Yiddish Heroism, Hebrew Tears,” Winter 2019), turns on a series of moments when people interviewed in the movie cry: the poet’s granddaughter when she reconstructs her memory of a German actor announcing the death of her grandfather during a performance in Berlin; the Yiddish scholar Avraham Novershtern when he describes Sutzkever requesting funding for his journal Di goldene keyt from the general secretary of the Histadrut in 1948, unaware that the man had just lost his son in the War for Independence; and Ruth R. Wisse as she describes an encounter with Sutzkever, who accused her of not understanding the Holocaust. Last but not least, Ms. Horn also describes herself shedding tears at a security checkpoint in Israel.

I found this the wrong tone for a review of a movie about a great poet and a wonderful human being. The last incident, the encounter with the soldier at the checkpoint, was, I thought, too much. The story of Sutzkever and of Yiddish poetry, even in Hebrew translation, does not need the embellishments of sentimentality.

Anita Shapira

Tel Aviv University

I am the director and screenwriter of the film Black Honey, The Life and Poetry of Avraham Sutzkever. Dara Horn’s essay is the first article written about any of my films that moved me to respond—to start a dialogue with her text.

From the title on, Horn’s “Yiddish Heroism, Hebrew Tears” is a revolutionary and subversive attempt to challenge the consensus that Yiddish is essentially the language of diaspora, of surrender, of helplessness and hopelessness, whereas Hebrew is the language of the victors who have taken control of their destiny. Here, the situation is reversed, revealing to us a new and exciting alternative for Jewish thought. Horn’s article exposes the very conceptual roots that guided me in making this film.

The more we study and research the Holocaust, the more helpless we remain in the face of human existence. Attempts to give artistic expression to what happened “over there” are swallowed in a black hole. Theodor Adorno famously said that “writing poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” The poet Avraham Sutzkever, on the other hand, climbed to dizzying heights of harmonious, musical, refined poetry—at the height of the extermination in the Vilna Ghetto. Like the sages of the Kabbalah, he redeemed the sparks from within the fragments of catastrophe—and thereby literally saved his own life. Even Sutzkever, however, as Ruth R. Wisse says in the film, never spoke about what actually happened in the ghetto. As the French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard put it, Auschwitz was an earthquake that destroyed all seismographic devices.

Another idea that guided my work, which Horn beautifully elaborated upon, was that the film should not be a nostalgic journey toward the Yiddish past but an attempt to enrich our spiritual and cultural world and derive inspiration from the world of the diasporic Jews. As the late Rabbi Shimon Gershon Rosenberg said, “The long years of the diaspora did not pass for us to disown them, but for us to internalize them, even while we are a free people in our country.” Yiddish—a language with no borders, no bureaucracy, no army or police—meets the modernized ancient Hebrew that lives vibrantly, if not wildly, in the here and now. But as Horn reminds us (and Agnon reminded Bellow), it is only in Hebrew that our texts in other languages will be preserved—hence, the Hebrew translation of Sutzkever’s oeuvre is a project of commemoration, of resurrection.

Uri Barbash

Tel Aviv, Israel

Dara Horn Responds:

I thank both Anita Shapira and Uri Barbash for their thoughtful letters. Professor Shapira is utterly correct that Sutzkever is an unsentimental poet. My review, however, was not of his poetry but rather of the film and how it inverts the traditional Zionist disdain for sentimentality (I am reminded of a sarcastic poem by Yehuda Amichai entitled “You Mustn’t Show Weakness”). What I found amazing about Black Honey was how it showed not only the power and unsentimental beauty of Sutzkever’s life and work but also the astonishing way that his utterly disciplined poetry opens the emotional floodgates of others. Barbash could have easily made a film that simply told the phenomenal story of Sutzkever and his work. He did that, but he added another layer by baring the emotional responses the poet has evoked in contemporary readers—which are ultimately responses to the tragedies and triumphs of the last 70 years of Jewish life. Uri Barbash’s eloquent letter and his film express this far more directly than I did.

Was Lincoln Jewish?

Stuart Schoffman’s provocative article “Was Lincoln Jewish?” (jewishreviewofbooks.com, February 12, 2019) mentions both Daniel Boone and Abraham Lincoln as possible Melungeons (southerners of mixed, partly Sephardi, heritage). As it happened, the Boones and the Lincolns were immediate neighbors in Berks County, Pennsylvania. Both families were prominent in local affairs and indeed intermarried. The Boones were Quakers from Devonshire. Abraham Lincoln the elder married Anne Boone, first cousin to Daniel. Through her the Lincolns became associated with the local Friends meeting, and both Boones and Lincolns are buried in its cemetery. The genealogy of Squire Boone, father of Daniel, is well known and goes back to the Plantagenet kings, as is the background of the Lincolns of Exeter Township. I think that the likelihood of Melungeon ancestry in either family is between slim and none. I happen to know all of this because I was born and grew up in Berks County, where we are very proud of our landsmen, the Boones and Lincolns.

Mimi Miller

via Facebook

The Rebbe and the Professor

Ariel Evan Mayse’s translations of the correspondence between Salo W. Baron and Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneerson (“The Rebbe and the Professor,” Fall 2018) were incredibly evocative, illustrating in two short letters the worlds of difference between two types of modern Eastern European Jews, the Hasid and the university-educated professor, their contrasting approaches to reestablishing Jewish life after the Holocaust, and the role of the Jewish cultural treasures plundered by the Nazis in that process.

Dana Herman’s fine dissertation (“Hashavat Avedah: A History of Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, Inc.”) treats the history of both Baron’s initial organization, the Commission on European Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, and its successor, Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, Inc., which was only given the authority to work in the Offenbach Archival Depot in 1949. Before then, Max Weinreich, Lucy Schildkret (who became Lucy Dawidowicz), Seymour Pomrenze, and many others worked tirelessly to save and redistribute the libraries and archives brought to the depot. Gershom Scholem had a bibliophilic field day in Offenbach before Baron’s organization got there.

Finally, I wish Dr. Mayse could have said more about Baron’s comment, “To my chagrin, the Yiddish language neither trips off my tongue nor flows from my pen.” Was he telling the truth?

Nancy Sinkoff

Rutgers University

The Transjordan Question

In “Chaim of Arabia: The First Arab-Zionist Alliance” (Winter 2019), Rick Richman states that the Zionist movement in 1919 agreed that the boundaries of the Jewish national home meant “leaving almost all of Transjordan to the Arabs.” This, however, does not agree with Chaim Weizmann’s statement before the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine, on July 8, 1947, where he made clear that “Palestine” was in 1919 understood as “Palestine and Transjordan.” He stated, “[The Transjordan] was cut off . . . at a moment’s notice. First you amputate Palestine. You cut off a country which is three or four or five times the size of Palestine, and then you turn round on poor Zionists and tell them, you are a small country; you cannot bring any population.” In other words, 28 years after the Versailles conference, Weizmann still felt that certain tracts of Transjordan (currently Jordan) were also meant to be included in the future Jewish national home. If so, then the separate Transjordan created by Winston Churchill, as colonial secretary, in 1921, in fact was an Arab Palestinian state. In 1948, when it absorbed the major Arab settlements in the West Bank and changed its name to Jordan, it was, in fact, a Palestinian state. But the name was only revived when Jordan attacked Israel on June 6, 1967, and consequently lost the West Bank to Israel occupation. Then came the outcry for a Palestinian state. But isn’t Jordan itself (even without the West Bank) also a Palestinian state?

Dr. Mordecai Paldiel

New York, NY

Correction

The photo on page 25 of our Winter 2019 issue was of the German musician Heinrich Ehrlich, not Henryk Ehrlich of the Polish Bund. We regret the error.

Suggested Reading

A Tale of Two Night Vigils

The tradition to stay up all night studying on Shavuot is far more well-known than the tradition to do so on Hoshana Rabbah. Neither would have been possible without Kabbalah and caffeine.

Super Stan

Even in comparison with so many other contributions to American popular culture and entertainment, comic books are an especially Jewish story.

Wishful Republic

What lessons can be learned from the city of Haifa, and what does its culture suggest about the likelihood and limitations of a binational state?

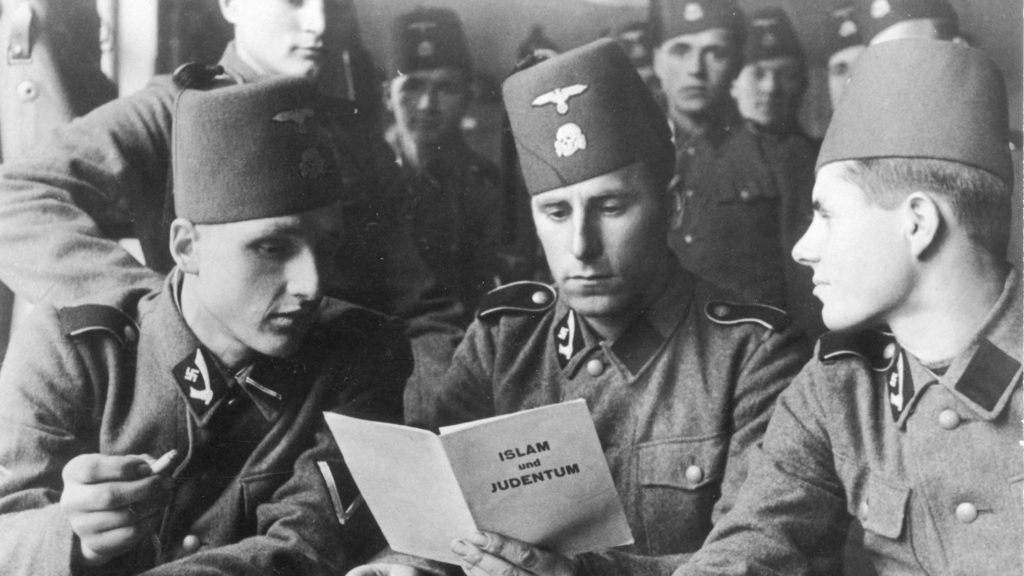

The Hands of Others

Many people know of Mufti al-Husseini's SS activities. But how many Arabs shared his admiration for Hitler and attraction to Nazism?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In