Diaspora Divided

Peter Beinart’s new book belongs to an as-yet-unnamed but increasingly common genre: the volumes that publishers commission and rush into print after the hullabaloo generated by a controversial article. Sometimes, these productions consist of little more than the original article, writ long. But sometimes, a book comes along that shows that its author has learned something from the heady—if brief—experience of being discussed everywhere. The Crisis of Zionism falls into the latter category, but just barely.

In his essay “The Failure of the American Jewish Establishment,” published in The New York Review of Books in May 2010, Beinart argued that young, liberal American Jews are disengaging from Zionism because they detest much of what Israel does. These people, he wrote, could only support a Zionism “that challenges Israel’s behavior in the West Bank and Gaza Strip and toward its own Arab citizens.” Because the major Jewish organizations have actively opposed this stance and continued to back Israel no matter what, “Zionism is dying among America’s secular Jewish young.”

Critics of Beinart’s piece rightly complained about its disregard for the security dilemmas facing the Jewish state. They highlighted the fact that in an article charging Israel with responsibility for ending the occupation, Beinart mentioned the threat of Hamas, Hezbollah, and Iran exactly once. His overall argument inflamed much of the Jewish world, prompting trans-Atlantic hand wringing about the future of the relationship between American Jewry and Israel. It also provided a rallying cry for many young, liberal American Jews—at Columbia University, where I was an undergraduate at the time, as well as at many other universities.

The book may very well become the topic du jour of world Jewry and other interested parties, fueling the uproar the article did so much to ignite. Among other things, the earlier piece set off a lively debate about whether Jews really are cutting loose from Israel, and, if so, whether Beinart, in pointing to the occupation and an unthinking American Jewish establishment, had correctly identified the cause. Some demographers, such as Theodore Sasson and Leonard Saxe, contended that the disaffection of young people was nothing new. Younger Jews have always felt themselves more distant from Israel but become more attached to it as they grow older. A new study that Sasson, Saxe, and others released late last year concluded that “there is no evidence of declining attachment [to Israel] across the generations,” nor any sign of “widespread alienation from Israel deriving from political disagreement.” In fact, they argue, initiatives such as Birthright—a free 10-day trip to Israel for Jews aged 18 to 26 that, since its inception in 1999, has brought more than 200,000 young Jewish adults to Israel—have significantly strengthened ties between American Jewry and Israel. In a 2009 study of Birthright participants five to eight years after their trips, Sasson and Saxe found that 58 percent reported feeling “very much” connected to Israel, while just 12 percent reported feeling “a little” or “not at all” connected.

The book may very well become the topic du jour of world Jewry and other interested parties, fueling the uproar the article did so much to ignite. Among other things, the earlier piece set off a lively debate about whether Jews really are cutting loose from Israel, and, if so, whether Beinart, in pointing to the occupation and an unthinking American Jewish establishment, had correctly identified the cause. Some demographers, such as Theodore Sasson and Leonard Saxe, contended that the disaffection of young people was nothing new. Younger Jews have always felt themselves more distant from Israel but become more attached to it as they grow older. A new study that Sasson, Saxe, and others released late last year concluded that “there is no evidence of declining attachment [to Israel] across the generations,” nor any sign of “widespread alienation from Israel deriving from political disagreement.” In fact, they argue, initiatives such as Birthright—a free 10-day trip to Israel for Jews aged 18 to 26 that, since its inception in 1999, has brought more than 200,000 young Jewish adults to Israel—have significantly strengthened ties between American Jewry and Israel. In a 2009 study of Birthright participants five to eight years after their trips, Sasson and Saxe found that 58 percent reported feeling “very much” connected to Israel, while just 12 percent reported feeling “a little” or “not at all” connected.

There are, to be sure, other demographers, such as Steven M. Cohen, a professor at Hebrew Union College, who agree with Beinart that American Jews are in fact growing more distant from Israel. Yet Cohen, in the very study that Beinart cited in The New York Review of Books, attributes this development not to politics but to intermarriage. Indeed, in a recent appearance before the Knesset, Cohen strongly reiterated his point: “The crime is distance from Israel, and the culprit is intermarriage.” Even though he admitted to agreeing with Beinart’s political agenda, Cohen stated that he refused to use the issue of distancing from Israel “to push that agenda,” because the way to get more Jews to care about Israel “is to strengthen Jewish life in America, not to focus on Israel’s multiple and horrible failings.”

Perhaps in response to such criticism, Beinart—though he doesn’t explicitly admit to it—largely walks back his theory of political distancing in The Crisis of Zionism. In fact, in direct contradiction to his article in The New York Review of Books, he endorses Cohen’s argument that, for the vast majority of American Jews whose ties to Israel are weakening, intermarriage is a more important factor than politics. Noting that the intermarriage rate among Jews today is “roughly 50 percent,” Beinart admits “the harsh truth is that for many young, non-Orthodox American Jews, Israel isn’t that important because being Jewish isn’t that important.” Later, he states, quite rightly, “it would be wrong to imagine that young, secular American Jews seethe with outrage at Israel’s policies.” “For the most part,” he writes, “they do not care enough to seethe.”

Nevertheless, even as Beinart concedes that the politics of the occupation and the American Jewish establishment have not actually had the massive impact that he once attributed to them, he does insist that they are, in fact, alienating a concentrated, core group of liberal Jewish elites. These are the relatively few people who make up the independent minyanim and social justice groups that have sprouted up on the coasts in the past decade-communities, according to Beinart, that emerged because the Reform and Conservative synagogues in which their members had grown up had replaced Jewish study with “AIPAC-style Israel advocacy.” To correct for that imbalance, they now seek to “fuse religious commitment and liberal values.” And precisely because these Jews “care deeply about being Jewish,” he says, they “find Israel’s policies agonizing.” A poll cited by Beinart finds that 77 percent of these young people believe that Israel should freeze settlement growth and that only 23 percent of those who attend independent minyanim say they always feel proud of Israel.

What’s more, says Beinart, these young elites scoff at the language of “victimhood” promoted by the American Jewish establishment, with its ceaseless emphasis on the continued threat of anti-Semitism and Israel’s existence as a “victim-state, besieged by aggressors.” This narrative, in Beinart’s view, “too often [ascribes] criticism of Israel to a primordial hatred of Jews” and insults young American Jews by telling them, against their better judgment, to “start with the assumption that Israeli policy is justified, and then work backward to figure out why.” Having grown up in an age of Jewish power, the emerging leaders are unmoved by the story of Jewish weakness. The alienation of these young elites from Zionism, Beinart argues, “reflects the American Jewish establishment’s failure.” Given that these Jews are far more plugged into that establishment than the rest of their generation, he is, at least to some extent, likely correct.

Beinart is also right in asserting that these young elites, however tiny in number, are potentially of great importance. They will undoubtedly lead American Jewry in the coming decades and could serve as a counter-weight to the Orthodox who, according to Beinart, will increasingly dominate the pro-Israel community in the United States and infuse it with a commitment to Israel as a Jewish, rather than a democratic, state. The question for them, as Beinart writes, is whether they will bring their liberal values to the struggle for Israeli democracy or build “an American Judaism that averts its eyes from the Jewish state.” Ensuring that they embrace the former, as The Crisis of Zionism argues, will prove critical to the future of the American Jewish community and its bond with Israel.

Beinart sets out to convince the liberal elite to join the battle for Israel’s soul by sketching a bleak forecast of the country’s future and arguing that due to deepening paranoia, bigotry, and inertia, Israelis can’t change that picture without the moral suasion of their liberal American cousins. To begin with, Beinart writes, Israel’s continued occupation of the West Bank will force the country to choose one of two unattractive options: rule undemocratically over millions of Palestinians, thus remaining Jewish, but not democratic; or fully enfranchise those Palestinians, thus remaining democratic, but not Jewish. Indeed, according to Beinart, the true threat to Israel’s future is not Iran, Hamas, and Hezbollah. Instead, it is the “hundreds of thousands” of Palestinians who may soon march on Israel demanding the “complete equality of social and political rights” guaranteed by its declaration of independence but denied by its occupation. And it is the “illiberal Zionism” forged by that occupation, that “requires racism, and breeds it,” a racism that has now infected Israeli society inside the Green Line “spawning authoritarian” values such as deepening discrimination against Israeli Arabs and accusations of treason against left-wing Israeli Jews. “Israel’s physical survival,” he writes, “is bound up with its ethical survival.”

That ethical survival, according to Beinart, will depend on Israel’s willingness to accept that its military and economic might have given Jews a new kind of power. And with that power, Beinart writes, comes responsibility: the responsibility to recognize, far more than most supporters of Israel would readily admit, that the Jewish state plays a large part in shaping the threats that it faces. Given Israel’s outsized role in defining its relationship with its neighbors, Beinart argues, the country can only retain its liberal values by accepting the burden of redefining those relationships—especially the burden of ending the occupation. In his view, young, liberal American Jews can help “preserve Israeli democracy” by reminding Israelis that, through the occupation, they are “betraying the sacred mission to which we are called every Yom Kippur by the Prophet Isaiah: to ‘break every yoke’ and ‘let the oppressed go free.'”

Even if one objects to this kind of moralism, one has to acknowledge that Beinart has identified the genuine threat posed by the occupation to Israel’s future as a Jewish and democratic state. And if it’s in Israel’s existential interest to stave off that threat by withdrawing from the West Bank, then Beinart is right to say that continued settlement construction and subsidization—particularly in areas that Israel will need to forfeit in a future agreement—does “menace Israel’s future” by making it that much more difficult to leave and achieve peace. Israel must embrace some level of responsibility for the continuation of the conflict. But not the lion’s share—and that, unfortunately, is what The Crisis of Zionism strongly implies.

The problem begins with Beinart’s rehash of the past twenty years of the peace process, which is mostly familiar, and mostly false. To foist a greater portion of responsibility for the continuing occupation on Israel, Beinart maintains that the Jewish state is largely to blame for the collapse of the Oslo negotiations and subsequent failure to revive them. “It’s simply not true,” Beinart says, “that Israeli leaders have offered the Palestinians everything they could reasonably want, only to see their efforts scorned.” Despite the fact that the final offer made by Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak was “courageous and far-reaching,” he and previous prime ministers had failed to go beyond what Oslo required of them by curbing settlement growth and thus “embittered Palestinians every bit as much as terrorism embittered Israelis.” Beinart then takes convicted Palestinian terrorist Marwan Barghouti—sitting in an Israeli prison on five life counts for suicide bombings that he authorized—at his word when he says that it was Israel’s settlement policy, and not its existence, that caused him to become “a key instigator of the second intifada.” Once “many Palestinians were ready for war,” Ariel Sharon “lit the fuse” by visiting the Temple Mount in September 2000. And when Sharon became prime minister, his disengagement from Gaza, which carried the threat of civil war in Israel, was nothing more than a cover for his plan to turn the West Bank into “Bantustans.”

The story continues in this vein up to the present. In Beinart’s telling, every Israeli leader—after Rabin—thought to be making peace was, in fact, either failing to present a serious offer or implementing some covert scheme to diminish any future Palestinian entity as much as possible. This revisionist view is, at best, a minority position. The mainstream consensus—held by, among others, Bill Clinton and his chief negotiator for the peace process, Dennis Ross—is that, in Ross’ words, Yasser Arafat never demonstrated “any capability to conclude a permanent status deal.” And Condoleezza Rice, in her recent memoir, argued that the concessions later proposed by Ehud Olmert were made in good faith, only to be refused by Mahmoud Abbas.

But leaving aside peace process historiography, the most important defect of Beinart’s argument is that it essentially exonerates the Palestinians of any accountability. While he approvingly cites, for example, former Palestinian negotiator Nabil Shaath’s declaration that “probably the settlement issue was the single most important destroyer of the Oslo agreement,” he casts doubt on the notion that any factor on the Palestinian side—like, say, the unrelenting demand for the right of return—truly impeded a deal. Elsewhere, Beinart’s bias seeps in through suggestive language. He begins one sentence with the words “were Israel to permit the creation of a Palestinian state”—as if Jerusalem were just one reluctant nod away from reconciliation with its neighbors.

There are, of course, all the necessary caveats. In discussing the reasons behind Hamas rocket fire on Israel, Beinart admits that it would be “unfair” to say that Israel’s embargo of Gaza “caused” the bombardment. Yet just afterward, he argues that Israel’s policies nonetheless “provided Hamas a rationalization to keep launching them.” Elsewhere, Beinart grants that “Hamas was not innocent” of any responsibility for sparking the 2008 war in Gaza, mentioning in passing that it had abducted the Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit and refused to return him. Yet, he asserts, “the basic point remains: the Israeli government did not do everything it could to find a diplomatic solution.” Yes, Beinart concedes, “in Arafat and Hamas, Israel has been unlucky in its adversaries.” But Israel must accept that it has “shaped the behavior of those adversaries.” In Beinart’s Middle East, every Palestinian action has a greater and opposite Israeli pre-action. If, as Beinart says, American Jews have “taken the messy reality of the Oslo process and scrubbed it clean of Israeli culpability,” then he has done much the same for the Palestinians.

Beinart thus commits the soft bigotry of low expectations, robbing the Palestinians of their own share of responsibility for making peace. And, with only one side of the picture to work with, he has left himself with only part of the frame for understanding the real security situation in the region. Perhaps the most egregious example of this is Beinart’s treatment of Israel’s disengagement from Gaza and subsequent attempts to deter Hamas. At the beginning of the book, he attributes disintegrating relations between Israel and Turkey to the Jewish state’s 2008 war in Gaza and subsequent killing of eight Turkish militants while confronting the flotilla. Later, he condemns Israel’s behavior in the Gaza war, devoting nearly a page to detailing the damage that the IDF inflicted and describing Gaza as “a fenced-in, hideously overcrowded, desperately poor slum from which terrorist groups sometimes shell Israel.” Yet after bashing Israeli deterrence in Gaza-blaming it for the majority of Israel’s troubles over the last five years-Beinart is suddenly prepared to endorse it while prescribing policy for Israel’s withdrawal from the West Bank. In the event of a pullout from the area, he admits, Israel will have to worry about potential rocket fire. But the “best way to combat that threat,” he argues, is, among other methods, “a credible deterrent so that Hezbollah, Hamas, Syria, and Iran know they will pay a severe price for bloodying the Jewish state.” What does that mean if not that Israel must be prepared to use in the West Bank at least the same amount of force as it deployed in Gaza?

This is a pitfall that Beinart might have avoided if his attention had been fully focused on Israel’s

security dilemmas. But he is, instead, more preoccupied with what is going on in the heads of certain young American Jews than with realities on the ground in the Middle East. As far as he is concerned, it’s the job of American Jewry to remind Israel that, despite the past twenty years of Arab rejectionism, the responsibility to end the occupation continues to rest squarely on its shoulders. This mission, he suggests, derives from a tradition of liberal activism that emerged out of opposition to segregation and the Vietnam War, one in which American Jews defined their identity by standing, first and foremost, with victims. By criticizing the occupation, the young elites can affirm that identity and rescue Zionism.

The Crisis of Zionism extends this argument in two very odd chapters of psychobiography of Barack Obama and Benjamin Netanyahu. Beinart argues that Obama, due to friendships with dovish Chicago Jews and his reading of a David Grossman novel, is the “Jewish president,” the torchbearer of liberal Zionism. Meanwhile, according to Beinart, Netanyahu’s Jewish lineage runs inescapably through his right-wing revisionist father to the “brutal” Vladimir Ze’ev Jabotinsky, rendering Bibi little more than a vector for their territorial maximalism and anti-Arab bigotry. Beinart thus makes a tantalizing offer to the young elites: by criticizing the occupation, they can stand by Zionism and join their liberal hero, Obama, in his attempt to do battle with the racist Netanyahu.

Beinart proposes this model of Zionism, at least in part, in the belief that it is what the young elites want. According to a study that he quotes, these non-establishment Jews “are far more likely to invoke collective memories of the civil rights movement, the labor movement” than the Holocaust or the founding of Israel. Indeed, Beinart’s attempt to present a palatable Zionism to the young elites is the true reason behind his shallow analysis of Israel’s security situation. It’s not just that he has a one-sided view of the conflict, nor just that he is narrowly concerned with one segment of American Jewry—it’s that he is presenting a specific narrative that will appeal most to the young, liberal Jews who naturally find it easier to associate with the Judaism of humanitarianism than with the Israel of occupation. However noble in its intent, the project is sure to backfire because it depends on a false and simplistic image of the Jewish state—one that will only repel the very Israelis these emerging American Jewish leaders are ostensibly supposed to persuade.

Beinart proposes this model of Zionism, at least in part, in the belief that it is what the young elites want. According to a study that he quotes, these non-establishment Jews “are far more likely to invoke collective memories of the civil rights movement, the labor movement” than the Holocaust or the founding of Israel. Indeed, Beinart’s attempt to present a palatable Zionism to the young elites is the true reason behind his shallow analysis of Israel’s security situation. It’s not just that he has a one-sided view of the conflict, nor just that he is narrowly concerned with one segment of American Jewry—it’s that he is presenting a specific narrative that will appeal most to the young, liberal Jews who naturally find it easier to associate with the Judaism of humanitarianism than with the Israel of occupation. However noble in its intent, the project is sure to backfire because it depends on a false and simplistic image of the Jewish state—one that will only repel the very Israelis these emerging American Jewish leaders are ostensibly supposed to persuade.

Even more damning, Beinart’s proposal for American Zionism is the very mirror image of the simplistic establishment line that he devotes his whole book to tearing down. In his attempt to offer young Jewish elites a Zionism that allows them to skip the “messy, frightening debate over Israel’s future,” he substitutes the old model of one-dimensional support with a new model of one-dimensional criticism. Having fled right-wing simplicity, Beinart loops directly back to its twin on the left. In doing so, he fails to establish the balance that American Jews so desperately need in their approach to Israel. And he alienates Israelis, who know and live a very different reality from the one he presents. That’s why those who embrace The Crisis of Zionism—especially the young, liberal elites for whom it is intended—risk dooming themselves to irrelevancy.

Suggested Reading

Palestine Portrayed

The 1948 War and the problems it left unresolved have returned to the top of the agenda for both diplomats and historians.

Kabbalah in 18th-Century Prague: A Response and Rejoinder

Sharron Flatto and Allan Nadler exchange views the Prague golem, Kabbalah, and Ezeliel Landau.

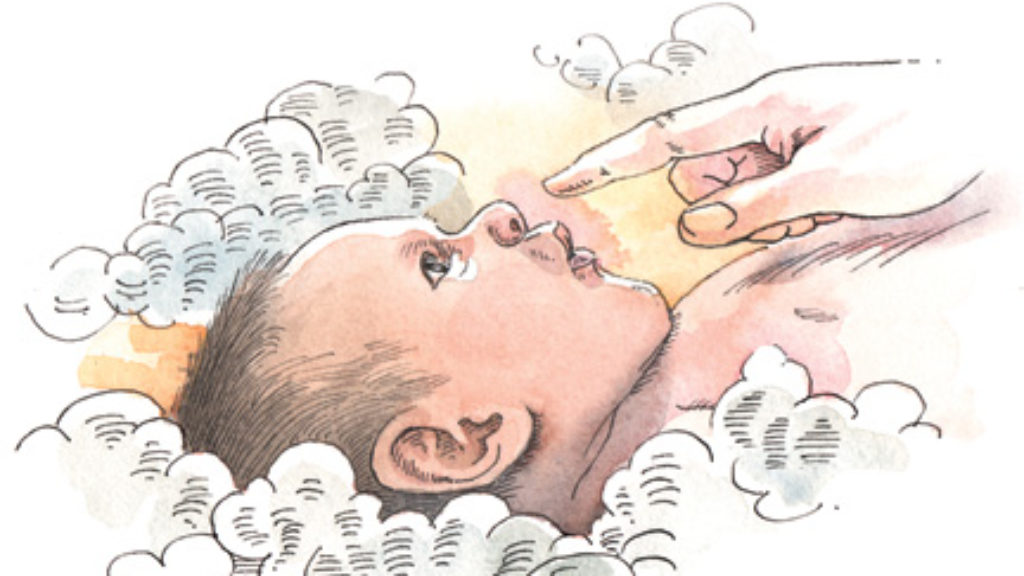

How the Baby Got Its Philtrum

The idea of learning as a recovery of what we once possessed is what makes Bogart’s bubbe mayse, and ours, so memorable: We can all touch that little hollow and feel the impress of forgotten knowledge.

Chaos in the Wilderness

Unlike reporters who are happy to rework official government statements, Mohannad Sabry reports on the Sinai by drawing on a broad network of sources in the region.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In