To Whom It May Concern: Mordecai Kaplan the Diarist

One Friday evening in 1932, Mordecai M. Kaplan decided to pay a Shabbat afternoon social call on his young Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS) colleague Louis Finkelstein, whose wife, Carmel, had recently given birth. Hewing to the protocols of middle-class urban life—popping over unannounced to a colleague’s house was just not done—Kaplan asked his wife, Lena, to first telephone the Finkelsteins to make sure they’d be welcome.

The maid who answered the phone informed Lena that neither Dr. nor Mrs. Finkelstein would speak on the phone on the Sabbath, but apparently also assured her that they were welcome to come by. When the Kaplans arrived the next afternoon, they found the apartment door open so that they didn’t have to ring the doorbell. Finkelstein greeted them, wearing a yarmulke.

Later that evening, at his own table, Kaplan told his teenage daughters about the visit, but said nothing about the conversation, or even the new baby. Instead, he went on and on about Finkelstein’s “assumed airs of Orthodoxy,” from his refusal to answer the phone to his leaving the door ajar and wearing a “cap all the time.” His daughters were puzzled and pushed him to clarify his position. If he refused to travel on Shabbat, why did it bother him that Finkelstein refused to answer the phone on Shabbat? “I must admit that I was non-plussed,” Kaplan recalled. “What could I say?”

This little tale brings together several facets of Mordecai Kaplan’s extraordinary century-spanning life (he was born in a town outside of Vilna in 1881 and died in New York City in 1983). Sharply attuned to the social niceties of his time, he was also a radical bent on reconstructing Judaism for the modern world, whose followers and even children did not always understand the ever-changing details of his program. And he wrote it all down in a journal that he began in 1904 and kept continuously for close to seventy years, from 1913 until 1981.

For much of the twentieth century, Mordecai M. Kaplan turned up wherever and whenever American Jewish issues were at stake. Point to any American Jewish communal institution or undertaking—from the Modern Orthodox synagogue to the havurah movement, summer camp to rabbinical schools, little magazines to big conferences—and the chances are that Kaplan was involved, or in his words, a “public factor.”

Even more of a thinker than a doer, Kaplan also let loose a steady volley of innovative, controversial views on tradition and ritual practice, Zionism, the Jewish people, and God. In periodicals such as the Maccabean and the Menorah Journal and in sprawling, influential books such as Judaism as a Civilization—even the White House Library owned a copy—he made clear where he stood: squarely on the side of change and reappraisal. Judaism, according to him, was not merely a religion, let alone a set of dogmas, but an evolving culture or civilization, which had to be adapted to the modern world of science and democracy.

In this spirit, Kaplan didn’t just write his own material; he took on and reworked some of Judaism’s key texts. Long before niche haggadot were common, he came up with his own version of the Passover narrative—The New Haggadah—in which he eliminated a host of passages he deemed inappropriate for the modern Jew. These included the recitation of the ten plagues with which God punished the Egyptians and elements of the much-relished dayenu. A few years later, he put his Reconstructionist stamp on the Shabbat siddur and for these (and other) sins was excommunicated in 1945 by more than two hundred Orthodox rabbis, who formally damned anyone who dared to use it. (In his journal, Kaplan noted with astonishment that his JTS colleague, the distinguished talmudist Saul Lieberman, appeared to be obeying the ban against him.)

Where American Orthodox Jews reviled Kaplan’s radicalism, those more closely aligned with his views, like the members of the Society for the Advancement of Judaism, the liberal Manhattan synagogue he created in 1922, took a different tack: affectionate parody. Inspired by Gilbert and Sullivan’s patter song “I’ve Got a Little List” from The Mikado, this equally wry, knowing version, which Kaplan’s congregants performed at a Purim spiel in the late 1950s, had his number:

As I pondered Jewish problems in my studio, all alone

I made a little list—I made a little list

Of words, ideas and concepts that our people have outgrown

And that never would be missed, that never would be missed!

The asher bocher banu that was said before the Torah

(The Chosen-People concept that all modern minds deplore—ah)

The blood-and-thunder plagues and pests that made the Seder gory

The double standard bima that went back to ages hoary,

The personal Messiah on which the Orthodox insist—

They’d none of them be missed—they’d none of them be missed.

Kaplan’s journal renders him a more compelling figure than his daunting CV—or his posthumous reputation—would suggest. His daily musings offer a front row seat to the unfolding of modern American Jewish history, and with it, a sobering chronicle of the ups and downs, political machinations, and emotional costs of a life spent in Jewish communal service. Read alongside Kaplan’s steady stream of publications and pronouncements as a running commentary, or, better yet, as a counter-narrative, they take us inside his head, as he wrestles with himself and his demons, the ideas he midwifes, and the people he meets.

The journals are full of surprises, the most striking of which is that the man who inhabits them is not only the Olympian figure who strode across the modern Jewish landscape, busily reconstituting, revitalizing, and reconstructing everything in sight, but a much more tentative, even hobbled, soul. The voice that emerges from these pages is also far more fluid and engaging than the formal, stilted prose characteristic of much of Kaplan’s published writings or the scolding tone of his sermons. Judaism as a Civilization is undoubtedly a great and important book, but his private reflections—awash in juicy characterizations of congregants, colleagues, and family members as well as in shrewd observations of the contemporary scene—make for a rollicking good read.

In the early 1950s, Charles Angoff, a prominent editor and cultural critic, encouraged Kaplan to publish them. Flattered, he gave Angoff the green light, but then, almost immediately, his conscience got the better of his vanity. “I let myself in for an adventure which might have gotten me into hot water, if I didn’t put a halt to it,” Kaplan reflected, allowing that “I would not be able to face those people whom I lambast in the Journal.”

It was only in 1993, with the publication of Mel Scult’s Judaism Faces the Twentieth Century: A Biography of Mordecai M. Kaplan, which sensitively and incisively drew upon the journal’s contents,that any of the material became public. In 2001 Scult published the first of three volumes of selected entries from the diaries that span 1913 through 1951. (Another volume, edited by Eric Caplan of McGill University and covering the period 1951 through 1981, is currently in the works.)

In the fall of 1904, while ministering to the “clamorous demands” of the younger generation at Congregation Kehilath Jeshurun, a Modern Orthodox synagogue-in-the-making on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, Kaplan gave his diary a title for the first and only time: “Communings with the Spirit,” the words spelled out with an artful flourish. More working notebook than confessional, it served as a kind of theologian’s blackboard, a place to wrestle with the moral equations posed by Schopenhauer, Royce, and other prominent thinkers of the day whose thoughts Kaplan was busily absorbing between 1904 and the spring of 1906.

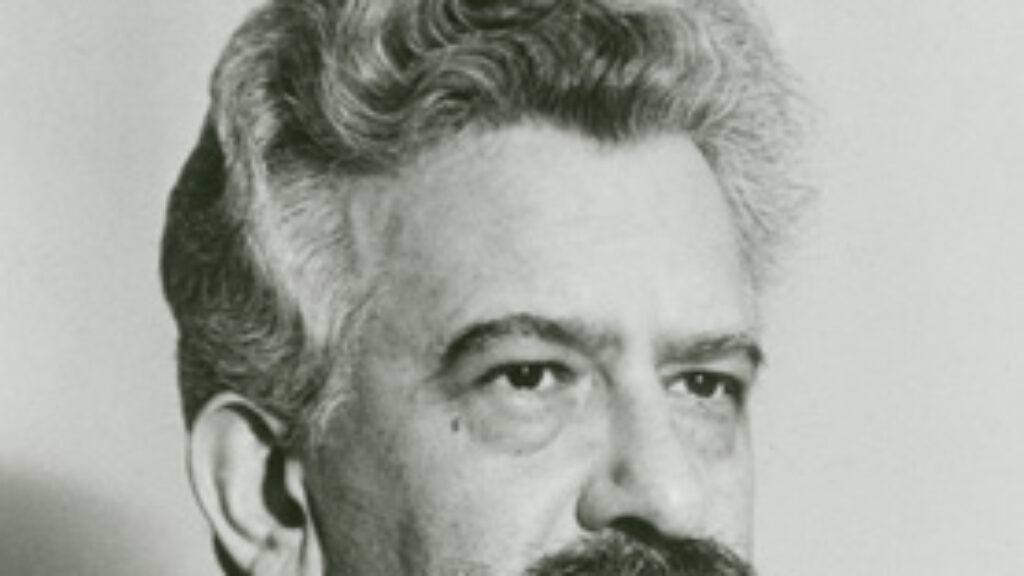

Mordecai M. Kaplan with his wife, Lena, and their daughters, Long Branch, New Jersey, summer 1916. (Courtesy of the Reconstructionist Archives.)

A second volume, picking up where the first one left off and running through 1907, shifted gears: more critical (“Am I beginning to see light?”), less philosophical, its personal ruminations more ample. “Enough of this moaning and groaning. It is unmanly,” he wrote in one characteristic entry in December 1906, taking his coreligionists to task for their “gushing sentimentality” when it came to tradition. And then, abruptly, or so it seems in retrospect, Kaplan put aside his notebook for five years, during which time he married, fathered two children, assumed the helm of the newly established Teachers Institute of the Jewish Theological Seminary, and was much in demand as a public speaker. It wasn’t until 1913 that he returned to journal keeping—and with a vengeance.

Each entry bore the day of the week, the date, and now and then, the place and the exact time of its composition as well. Occasionally, it took the form of a reminiscence. Presiding over the funeral of a longtime congregant would put Kaplan in mind of the time, back in the day, when he first stuck out his neck and got into trouble by saying something that irked some congregational macher. At other moments, a recollection would appear out of the blue, like one, dating from 1958, in which he tenderly recalled how Arnold Ehrlich, who, during his teenage years, tutored him in Bible, would say, “Bochur, bochur [the words spelled out in Hebrew], how do you understand the verse?”

The contents of his journal ranged widely, from accounts of classes taught, sermons given, meetings attended, and books read to plans for a summer vacation in Westport, Connecticut, during which he hoped to spend time in the company of Plato. Dinner table conversations with the “kiddies,” his beloved four daughters, also dot the narrative. Student shenanigans, the snubs of colleagues, campers’ antics, unresponsive audiences (“I felt as though I was talking to myself”), the foibles and follies of his congregants, which wilted his spirits, and the viability of Reconstructionism at which he kept “hammering away”—all this was grist for his mill.

Not immune to pleasure or satisfaction—on a good day, Kaplan would thrill to a new book and delight in his children and grandchildren—he was far more inclined to be aggrieved: “in the dumps,” exasperated, and flabbergasted at being misunderstood.

Often following immediately on a grumpy or gossipy entry, only a thin blue line and a loosely grouped array of x’s breaking his anecdotal stride, Kaplan took up topics like God, Zionism, the role of the self, the meaning of faith in the modern era, the fate of American Jewry, or the purpose of the Passover Seder.

He also wrote of his influences, crediting John Dewey and Ahad Ha’am with having “helped to mold my life more than any other person in the world, past or present.” Dewey’s democratic pragmatism and Ahad Ha’am’s cultural Zionism clearly informed Kaplan’s vision of Judaism as a civilization that must be rationalized and made more accessible. He wrote, too, of more traditional touchstones even if he went on to rewrite them. Maimonides’s thirteen principles of faith, for instance, inspired Kaplan’s “The Thirteen Wants,” in which Judaism emerges as a humanist project, as the first four suggest:

1. We want Judaism to help us overcome temptation, doubt and discouragement.

2. We want Judaism to imbue us with a sense of responsibility for the righteous use of the blessings wherewith God endows us.

3. We want the Jew so to be trusted that his yea will be taken as yea, and his nay as nay.

4. We want to learn how to utilize our leisure to best advantage, physically, intellectually, and spiritually.

In the aftermath of World War II, Kaplan read the new existentialists and Christian religious thinkers from Reinhold Niebuhr and Paul Tillich to Norman Vincent Peale (whom he likened to a prosperous and self-satisfied stockbroker). In a journal entry, he fretted over why Tillich’s understanding of God as the ground of all existence was applauded while the God to whom he, Kaplan, addressed his prayers was mocked by critics as “to whom it may concern.”

Kaplan took great pains with his journal writing. He didn’t simply jot down stray impressions or make off-the-cuff remarks. His entries were well crafted, carefully edited, deliberate. Claiming he had to “go through the tortures of the Laocon” [sic] to marshal his thoughts, Kaplan routinely tightened and polished them, crossing out a word, a phrase, or even an entire sentence, substituting another that was more precise, punchier, or softer. At other moments, when in high dudgeon, which happened a lot, Kaplan would come at something that troubled him—his relationship with his students, the viability of Reconstructionism, or his legacy—with the full force of his formidable intellect and prickly temperament.

As a professor of homiletics, midrash, and religious philosophies at JTS from 1909 until 1963, Kaplan was known to be a demanding, sometimes acerbic teacher. The diaries, though, reveal the degree to which teaching at 3080 Broadway took a toll on him. In the wake of a disappointing class in late August 1934, he wrote:

As a result I now feel all fagged out, not so much because of the physical effort expended as the mental strain of having to kindle wet wood, so to speak. This time, the Seminary men irritated me with their foolish questions . . . [to which] I was too dumbfounded to reply in consecutive sentences. I blurted out incoherent statements. I just sputtered.

The classroom wasn’t the only thing that left Kaplan sputtering. The fate of Reconstructionism also bedeviled him, prompting him repeatedly to question whether constituting it as a denomination made sense. He much preferred to flag his distinctive approach to modern Jewish life as a sensibility, a “way of talking” that could cut across Reform, Conservative, and Orthodox Judaism. Once, in a lyrical frame of mind, Kaplan analogized the relationship of Reconstructionism to the established denominations as that of an “electric current to the lighting system of a city.”

And yet, propelled by Ira Eisenstein, his former student, son-in-law, and right-hand man, Kaplan eventually endorsed the notion of creating a new denomination, even as he voiced some of his recurrent reservations in a November 1963 entry:

I therefore would like to see Reconstructionism act as a leaven in each of the existing denominations . . . instead of itself give rise to a new denomination. Should the latter eventuate, it would defeat the primary aim of the movement—to bring about an awareness among Jews of whatever they have in common.

Given Kaplan’s lingering doubts, one wonders whether his change of heart was motivated by loyalty to Eisenstein. After all, the two worked side by side for years, even living together during several summers in a rented home on the Jersey Shore.

Eisenstein, who for a while also kept a journal, recalled how difficult he found these instances of family togetherness. Instead of frolicking in the surf, Kaplan worked all the time—“he sits and sits and sits, his pen poised”—and was “no help, either, when it comes to the observance of Jewish ritual,” going one way while the family went another. Lena’s deification of her husband—“nobody exists for her outside him”—and her “constant hurrying” about the house, he wrote, also “drives me nuts.”

Despite the family squabbles, the setbacks, and the disappointments that colored his life, Kaplan, by anyone’s lights, had an enviable one. He enjoyed the blessings of good health for most of it, loved and was loved, and kept on working and writing in his journal until the tail end of his very long life—he died at age 102. Despite his accomplishments, peace of mind and a sense of completeness eluded him.

Mulling over the history of the Society for the Advancement of Judaism (SAJ) in December 1963, more than forty years after its establishment, Kaplan tied the congregation’s fate to that of American Jewry writ large and came up short:

Those who seceded from the Jewish Center and formed the S.A.J., though limited in their knowledge of Judaism, were sufficiently imbued by its general spirit . . . to feel a sense of responsibility for keeping Judaism alive.

. . . After a number of years during which the generation that helped me found the S.A.J. began to dwindle away, it was followed by a generation which knew even less about Judaism and felt less of a responsibility for its conservation and enhancement. Since then it has been harder to innovate, due not so much to active resistance as to sheer apathy or indifference.

From time to time, Kaplan grew weary of documenting his life, let alone keeping modern Jewish life afloat. Pooh-poohing the exercise as little more than “dawdling or doodling,” or, worse, as a “kind of book-keeping, dry, dull and mechanical,” it stole him away from other more significant ventures. But no sooner would Kaplan forsake his Parker pen and ease up on his writerly ritual than he would complain—in his journal, of course—of feeling adrift, “agitated and restless,” without it. He confessed to a “compulsive drive to ‘photograph’ my personal experience,” while hoping that a “future historian will chance across this journal” and learn of the “irrelevance and futility of the contemporary efforts at keeping the Jewish tradition alive”—by which, of course, he meant his own.

To remain constant, Kaplan filled his journal’s fly leaves with quotations and bromides from a magpie-like assortment of fellow diary keepers and creative spirits, among them Emerson, André Gide and Khalil Gibran, Ben Hecht and Hegel, D. H. Lawrence, Lewis Mumford and Thoreau. By placing himself within their company, Kaplan sought to lay claim to a shared distinction. He needn’t have. Of a piece with their author, his communings are in a class by themselves.

Suggested Reading

History with a Flourish

So much gets lost in translation—and to history—when household items, heavy with use, first assume the status of heirlooms and then land in museum vitrines, heralded as art rather than history.

Heschel Transcendent

Abraham Joshua Heschel’s intellectual peers included Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, Reinhold Niebuhr, and the Lubavitcher Rebbe. His main thought, Shai Held argues, was of transcendence.

Hidden Master

The closer we look at Green's theology, the more radical it turns out to be.

Graven Images

“How do you like my drawing?” Franz Kafka wrote his fiancée Felice Bauer. He took art seriously, and now, finally, we can answer the question ourselves.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In