The Milchik Way

Hankering for blintzes? No, not the pallid, tasteless logs available in the frozen foods section of your local supermarket, but the authentic kind once likened to “pot cheese in an envelope.” Hanker no more. They can be found—and consumed vicariously—in Ben Katchor’s homage to the dairy restaurant of yesteryear, where golden-hued blintzes, chubby with cheese, dominated the bill of fare, alongside protose steak, a faux meat product made from vegetables and nuts; hearty bowls of kasha in milk; and a renewable supply of onion rolls.

At a time when restaurants of every sort, from the most elegant of establishments to their hole-in-the-wall counterparts, have become an endangered species, a casualty of COVID-19, this book’s long-awaited publication is an especially welcome reminder of their centrality to the civic square—and to history.

A self-styled “stage-magic realist” and graphic artist whose wide-ranging body of work—in print, on the stage, and in the exhibition gallery—spins the dry facts of American urban history into the gossamer of fantasy, Katchor has garnered legions of fans as well as a MacArthur Fellowship for his unique compositions. “I am deeply engaged by the conflict, by the tension, between words and images—the way in which the image does not have just to illustrate the words but can range quite afield,” the author of Julius Knipl, Real Estate Photographer and The Jew of New York told Lawrence Weschler, whose affectionate portrait of the artist appeared in The New Yorker in 1993.

More than 25 years later, Katchor has once again done right by the creative tension between word and image in his absorbing, sly, and occasionally maddening new book on the history of the dairy restaurant, a former fixture of the American Jewish urban landscape. Where the kosher deli, that other storied American Jewish culinary institution, swaggered, its salamis hanging from the ceiling “like trophies of some unspoken success,” the dairy restaurant had a much more modest footprint, which captured the artist’s eye and beguiled his imagination:

Wandering the streets of New York during my early adult years, I frequented a species of dairy restaurant that seemed to have always been there. . . . It was the appearance and atmosphere of these dairy restaurants that attracted me. I assumed that the resigned and forlorn air that filled these places was due to their being businesses in their final decline. Their customers had died or moved away, the cuisine they offered was no longer considered healthy or fashionable, and the owners did not want or expect their children to continue their line of work.

As much a visual experience as a textual one, The Dairy Restaurant is not a traditional narrative, not by a long shot. Drawn with the artist’s distinctive hand and affinity for gray wash, images of exterior signs and interior seating arrangements, of people, cows, and plates of food inhabit nearly every page, vividly recounting the story of the dairy restaurant’s evolution over time and space.

The text that accompanies these images is equally idiosyncratic; not so much composed as accumulated, it’s history à la carte. Where conventional historical accounts place a premium on context and a sustained narrative, not to mention a table of contents and formal chapters, this sprawling volume purposefully eschews all that. Instead, it throws everything it has at the reader: the intricacies of the Jewish dietary laws; the history of the restaurant, which first took off in Paris in the wake of the French Revolution; the relationship between temperance and its banishing of beer to vegetarianism and its embrace of milk; the emergence of the “milekhdike personality,” who preferred contemplation to action. Adam and Eve are present and accounted for, as are Pola and Salek Gefen, proprietors of Gefen’s Dairy Restaurant in the heart of the Fur District of New York, and, of course, Sholem Aleichem, whose exuberant celebration of the dairy palate Katchor shares with his readers:

From meat you have a soup, a roselfleisch, an esikfleysch, a roast . . . and that’s it. . . . From milk, however, you have milk, cheese, butter, sour cream, pid-smetene, whey, kasha with milk, noodles with milk, rice with milk, and teyglekh with milk. . . . The delicacies from cheese and butter, kreplekh and varenikes, and varnitshkes and kugel . . . and knishes and blintzes, tsores kneydlekh. . . . And how dear are the delicacies that one cannot remember!

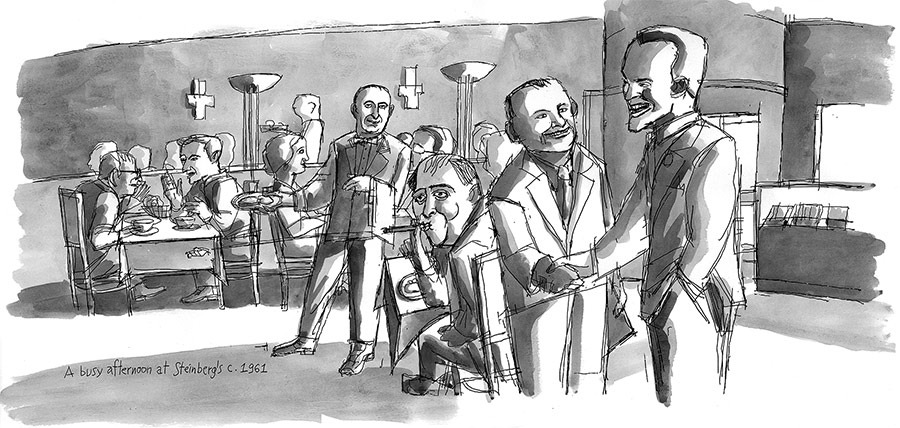

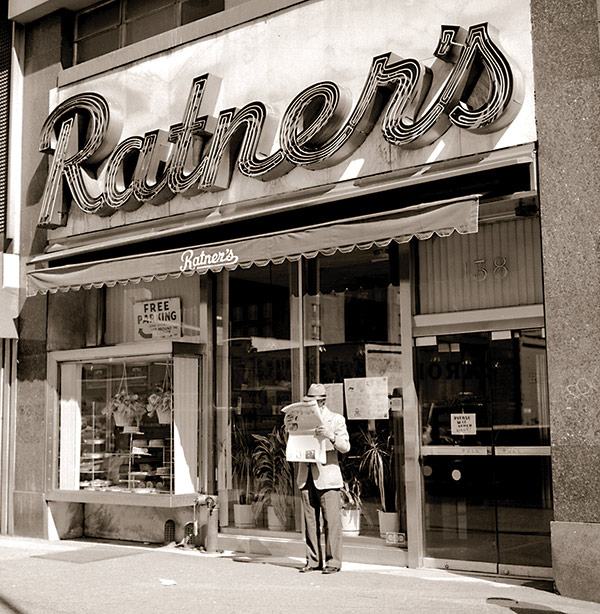

To help us remember, Katchor places brief, obituary-like descriptions of long-departed restaurants alongside the menus, reproduced in full, of Ratner’s on Manhattan’s Lower East Side and Steinberg’s on its Upper West Side, two of the more successful and long-running eateries of their kind.

These and other dairy restaurants were imported from the Old World, where Milchhallen (milk pavilions) were all the rage in late 19th-century urban parks, and plunked down in the New World sometime in the early 1900s. (“Trying to identify the earliest dairy restaurant,” Katchor confesses, “is like trying to find the site of the original Garden of Eden.”) On the Lower East Side and in other neighborhoods where city Jews lived and worked, eateries by the dozens offered patrons crowded menus in which the category of “delicacies” sat companionably next to that of “mushrooms and vegetables” and encompassed a stunning array of options, “none of which are known to have ever caused anybody stomach trouble.” Or so cheered Jacob Harmatz, one of the proprietors of Ratner’s, in a 1940 interview.

Customers, seated at a counter or a table fashioned out of Formica and stainless steel—both substances were easy to keep clean—could make a meal of vegetable liver salad and noodle chop suey with kasha, and no one, not even the crankiest of waiters, would say a word. He might roll his eyes at a customer’s odd juxtaposition of dishes but would do nothing to dissuade her. “Curated” meals, peppered with “the chef suggests,” were conspicuously absent. Anything on the menu might be paired with anything else.

Katchor seems to take his cue from these menus with their meandering columns of dense text; their indirection parallels and feeds his own. Though at the book’s conclusion he writes that there’s even more to be learned about the history of dairy restaurants in this country and abroad, that concession is to be taken with a grain of salt. Anything and everything related to the dairy restaurant, from soup to nuts, lives in this tell-all book, which works best when you succumb to its charms and go with the flow instead of holding it up to the light and strictures of concision and argument.

Comprehensiveness isn’t the book’s only striking feature. Equally noteworthy is what it doesn’t do. Katchor is no blissed-out foodie, rapturously extolling the virtues of one brand of cheese over another. I’d even go so far as to say that food doesn’t really fire his imagination. What nourishes his soul is the culture, not the cuisine, of the dairy restaurant, which, he wittily observes, provided “an environment in which customers could surrender to the milekhdike aspect of their personality.”

Recovering its mild-mannered patterns of sociability, its chatter and conviviality, drives him forward. That much of it was informed by “Yiddishkayt,” the constellation of behaviors, gestures, and sensibilities carried from the Old World into the New by Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, raises the stakes, prompting this keen-eyed observer of urban life to linger a while longer. And the more Katchor lingers, the more driven he is to secure the dairy restaurant’s place in history. A man on a mission, he writes:

It’s the twentieth-century Jewish dairy restaurant, possibly due to its utilitarian design and lack of picturesque ethnic qualities, that’s least memorialized and preserved. They did not attract boastful tourists or self-promoters in need of postcards to send home.

Relying on advertisements, literary references, interviews, newspaper accounts, photographs, and restaurant trade magazines as well as on ephemera such as matchbook covers and sugar cubes wrapped in printed matter, Katchor, a member of the British Matchbook Label and Booklet Society, painstakingly recreates a lost world.

Katchor’s gastronomic Atlantis could easily tilt over into sentimentality and pious nostalgia, but whimsy and bemusement save the day. Here, as in all of his other creations, he relishes the oddball personality and the curious detail that not only give rise to a chuckle but also cut through much of the heaviness, the glumness, we associate with tales of people, practices, and places that are no more. “Under the scrutiny of an optical loupe, the deluded historian sees below the surface of the printed objects,” Katchor writes in one characteristic passage. “The stain on a menu reveals the ingredients of a soup, the climatic conditions of the evening, etc.” Elsewhere, he attributes the popularity of dairy restaurants to the immigrant Jews’ poor dental health, speculating that its dishes required “less strenuous chewing” than meat. Though this hefty volume weighs in at nearly 500 pages, lightheartedness prevails throughout.

Still, there’s no getting away from the fact that, in Katchor’s universe, food is bound up with loss rather than sustenance. He mourns the passing of a way of life—“these intimations of a better time”—that once encompassed the simpler pleasures of the palate along with a place to hang one’s battered hat. Contemporary readers of The Dairy Restaurant may no longer be familiar with baskets of onion rolls set atop a stainless-steel counter, or, for that matter, with protose steak, but, in their current hungering for the kind of community this humble eatery once provided, they’re apt to recognize themselves.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Life with S’chug

Einat Admony, who was raised by an Iraqi mother and a Persian father in Bnei Brak and now runs gourmet Middle Eastern fusion restaurants, is a new wave balaboosta.

Vegetarian in Vilna

The long, brutal winters and meaty cuisine of Eastern Europe don’t immediately make one think of garden-fresh vegetarian recipes.

The Last Bedtime Story: Roz Chast’s Sort-of Tour Guide

Realizing that her daughter knows nothing of the urban wilderness her mother once inhabited, Roz Chast takes it upon herself to bequeath her accumulated wisdom in the method most natural to her, a comic book.

Chopped Herring and the Making of the American Kosher Certification System

In 1986, the discovery of non-kosher vinegar in a classic Jewish delicacy led to a revolution in kosher supervision.

Rochelle Mogilner Gastwirt

Jenna,

Your insightful review brought back many delightful memories of bygone days. Now to enjoy the book!

Philip Ladovsky

As your reviewer notes, Ben Katchor’s ode to the dairy restaurant plays on an air of nostalgia for the comfort and conviviality associated an with earlier era. But let’s not get too sentimental. The history is a nice background, but the dairy restaurant, to stay alive, has to make that dream taste good every time you’re there. As the owner/operator of one such institution (ours was established in 1912), I’ve observed that customers with a ‘hankering for blintzes” arrive with expectations of a tasty, fresh, well-prepared and satisfying meal. They’re not seeking a lost world, especially these days, when the losses have already piled up . They hunger for sustenance, for body and perhaps for soul. As your review concludes, contemporary readers— including a growing population of foodies — recognize the desire for simpler pleasures of the palate. As there are still plenty of places where this can be found, why mourn what isn’t yet gone?