Ten Duel Commandments

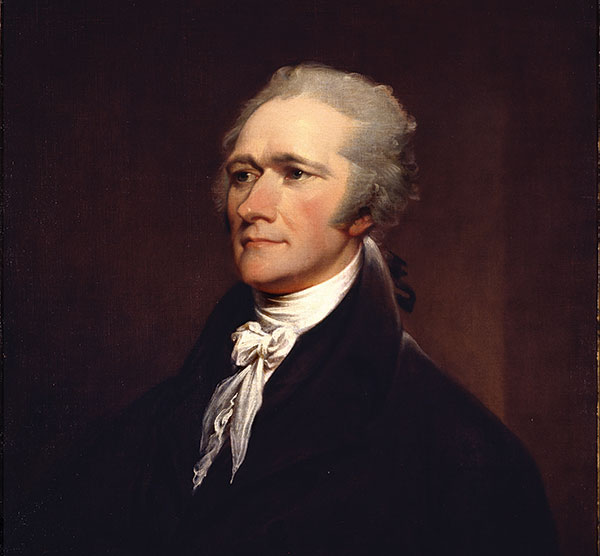

Hamilton, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s hit 2015 musical, opens by describing its hero as a “bastard, orphan, son of a whore and a Scotsman,” highlighting the steep obstacles Alexander Hamilton had to overcome on his way to becoming a founding father. Now historian Andrew Porwancher proposes adding another unpropitious identity to the list—Jew.

Was Hamilton Jewish? Most historians would say no; The Jewish World of Alexander Hamilton makes an intriguing though inconclusive case that the answer is yes, or at least “kind of.” Neither Hamilton himself nor any of his contemporaries ever said he was Jewish. Like many of the founders, he was not much of a churchgoer—he left religious matters to his wife, Eliza—but on his deathbed, with the bullet from Aaron Burr’s dueling pistol lodged in his spine, he took communion from the Episcopal bishop of New York. The bishop, who was a friend, initially refused, doubting the sincerity of the request. But insofar as Hamilton had a religion, it was Christianity.

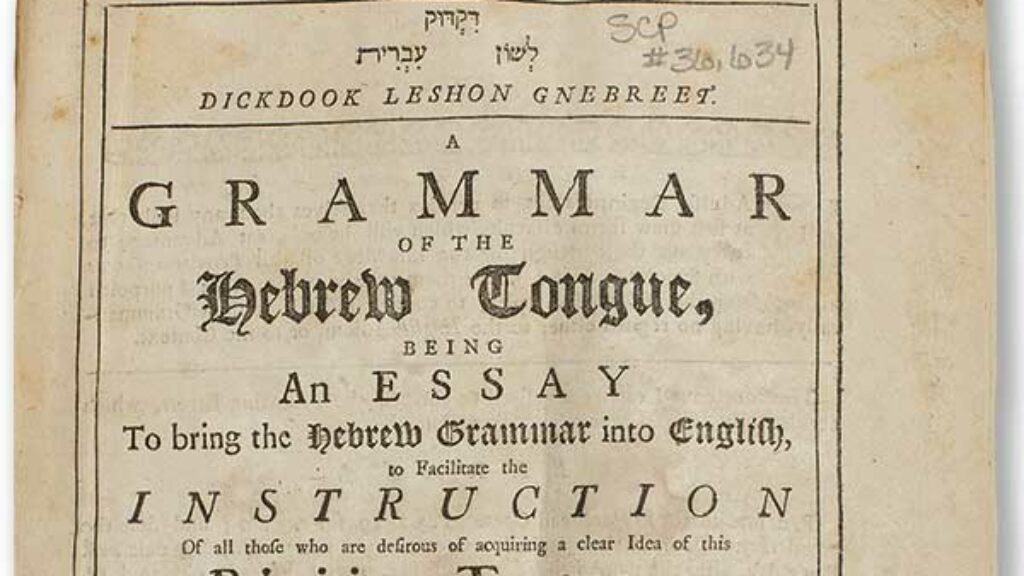

Porwancher hasn’t discovered any bombshell evidence to blow up this conventional understanding of Hamilton’s faith. Rather, he argues that previous historians and biographers have misread and underplayed a few key pieces of evidence about his early life. The most significant is a single sentence by his son John C. Hamilton, a historian who wrote his father’s biography in seven volumes. His account of Hamilton’s childhood includes this surprising anecdote: “Rarely as he alluded to his personal history, he mentioned, with a smile, his having been taught to repeat the Decalogue in Hebrew, at the school of a Jewess, when so small that he was placed standing by her side upon a table.”

Why was the young Alexander Hamilton being taught the Ten Commandments in Hebrew? John C. Hamilton implies that the story testifies to “the low state of education in the West Indies,” as though there were no better options on the island of Nevis, where Alexander was born around 1755. Porwancher writes that most biographers—including Ron Chernow, whose bestselling book on Hamilton inspired Miranda’s musical—have simply ignored this anecdote. Those who do take note of it suggest that Hamilton would have been unwelcome at an Anglican church–run school on account of his illegitimacy. He was born out of wedlock to Rachel née Faucette, a native of Nevis, and the Scottish settler James Hamilton—the whore and Scotsman of Miranda’s lyrics.

Porwancher isn’t convinced. He argues that neither Jews nor Christians would have permitted a Christian child to study in a Jewish school in that time and place. “There is ample reason to expect that Alexander would have only attended the Jewish school if the community’s Jews accepted him as a coreligionist,” he writes. But if neither of his parents was Jewish, why would young Alexander have been considered a member of the community?

Here Porwancher turns to a second piece of ambiguous evidence. One reason Hamilton’s parents didn’t marry is that his mother was still legally married to her first husband, Johan Levine (or Lewin or Lavien), a merchant living in the nearby Danish colony of St. Croix. The name certainly sounds Jewish, and while there is no ironclad evidence, Alexander Hamilton’s grandson Allan—who also wrote a biography of his famous ancestor—described Johan Levine as a “rich Danish Jew.”

Through skillful work in deteriorating Caribbean archives, Porwancher has discovered other suggestive facts. For instance, Levine sold his plantation to a Jewish buyer, implying communal ties. His son with Rachel, Peter Levine, was baptized in the Anglican church as an adult, which would have been necessary only if he was not baptized as a child—another sign that he may have been raised in a Jewish home.

If Johan Levine was Jewish, then Rachel would presumably have converted to Judaism to marry him. In that case, her sons with James Hamilton, who was certainly a Christian, would have been considered halakhically Jewish, since Jewishness is inherited matrilineally. As Porwancher writes, “The children of a Jewish woman who sheds her faith and hides her past are still legally Jews.” This would solve the mystery of why Rachel sent Alexander to a Jewish school and why the school accepted him.

Even if Porwancher’s suppositions are true—and they certainly seem plausible, though it’s unlikely they can ever be definitively proven—they would give Hamilton only a tenuous connection to Judaism. In any case, Por-wancher writes, “Any identity as a Jew that Hamilton may have had almost certainly died with his mother,” when he was thirteen years old. Should this change the way we understand the rest of Hamilton’s story—his unlikely ascent from provincial orphan to Revolutionary War hero, champion of the Constitution, and architect of the American economy?

Here, again, Porwancher’s answer can be summed up as “No, but.” Hamilton’s possible connection with Judaism didn’t shape his career or his convictions in any obvious way. Except one, perhaps: of all the founders, he had the most Jewish acquaintances and expressed the most positive views of Judaism. “Surely it is no mere happenstance that among the founders, Hamilton was the only one to attend a Jewish school as a boy and then cultivated the greatest involvement with Jews as an adult,” Porwancher writes.

A the title suggests, the book’s real subject is not what Jewishness tells us about Hamilton but what Hamilton’s story can tell us about the experience of Jews in his era. In tracing Hamilton’s Jewish connections, Porwancher shows how Jews negotiated the unprecedented freedom of the New World while dealing with lingering religious prejudice, economic rivalry, and legal disabilities.

The very fact that there was a Jewish school, or at least a “Jewess,” to teach the young Hamilton is a sign of the surprising ubiquity of Jews in the eighteenth-century Caribbean. The islands were devoted to sugar plantations, which were extremely lucrative for their British, French, and Danish rulers—and extremely brutal for the Africans they enslaved and worked to death. A slave in the Caribbean survived the inhumane conditions an average of just five years, Por-wancher writes.

Jewish merchants played a significant role in the sugar trade, aided by their far-flung family and communal networks. Most were Sephardi descendants of Spanish and Portuguese colonists, but there were also some Ashkenazi settlers from Central Europe, Johan Levine possibly among them. When Hamilton was born on Nevis, the English colony had about one thousand white inhabitants, and a visiting priest reported that “one 4th are Jews, who have a synagogue here.” He also noted that they “are said to be very acceptable to the country part of the island, but are far from being so to the town, by whom they are charged with taking the bread out of Christians’ mouths.”

The complaint that Jewish merchants were illegitimate competitors—because of their sharp practices or simply because they weren’t Christian—could also be heard in New York City, where Hamilton attended King’s College (the future Columbia University). Only about 250 Jews were living in New York at the time, about 1 percent of the population, but they played a disproportionate role in the economic life of a city that was already the nation’s financial capital. This bred resentments. Porwancher quotes a Massachusetts man who visited New York in 1765 and noted that local Jewish businessmen “sustain no very good character, being many of them selfish and knavish, (and where they have an opportunity), an oppressive and cruel people.”

The second half of The Jewish World of Alexander Hamilton shows that Hamilton, whose career as a lawyer and politician brought him into contact with many Jewish New Yorkers, was happily immune to such prejudice. His correspondence includes none of the slurs occasionally used by, say, John Adams, who once referred to a relative he disliked as “a perfect Viper—a Fiend—a Jew—a Devil.”

Hamilton, by contrast, was

responsible for what Porwancher calls “the most impassioned denunciation of

antisemitism in the annals of any founder.” It came during a long-running legal

battle in which he represented a New York merchant named Louis

LeGuen, who was suing his business partners for selling a cargo of cotton and

indigo at a low price, causing him a considerable loss. The trial and appeals

went on for years and became notorious, especially after the litigants started

to denounce one another in paid newspaper ads.

Hamilton found himself squaring off in New York’s highest court against opposing counsel Gouverneur Morris, a leading politician and one of the drafters of the Constitution. Morris argued that two of LeGuen’s key witnesses shouldn’t be trusted because they were Jewish, and “Jews are not to be believed upon oath.” This prompted an eloquent and successful rebuttal by Hamilton, who declared that Judaism, the religion of the biblical Israelites, was a “pure and holy, happy and Heaven-approved faith.” More, he insisted that justice should be blind to “all differences of faiths or births, of passions or of prejudices—all are called to acknowledge and revere her supremacy.”

Porwancher suggests that this vehement defense offers further confirmation of Hamilton’s Jewish identity, or at least his affinity for Jews: “Hamilton’s contemporaries remarked that no other trial in his illustrious legal career elicited from him a more emotional performance. Plainly, the case touched something deeply personal within him.” It’s a good example of how Porwancher’s thesis shapes his reading of the evidence as much as it is shaped by it. Hamilton’s passionate performance could be just as plausibly explained by his desire to make political capital out of his starring role in a prominent trial.

If Morris’s appeal to bigotry could fail so dramatically, was prejudice against Jews really as significant a force in early America as Porwancher often suggests? While he finds examples of anti-Jewish language from contemporary letters and newspapers, his frequent use of the term “antisemitism” feels anachronistic. Americans in Hamilton’s era did not think about Jews in terms of ideological hatred. Those who did harbor negative feelings were often driven by religious and philosophical ideas about Judaism that had little to do with actual Jews, whom most Americans never encountered.

Several of the founders harbored a Voltairean disdain for Judaism, which they blamed for giving the world the Bible. But Porwancher tends to see more baleful intentions in such sentiments than they deserve, in one striking instance misreading his source to do so. In a discussion of the founders’ views of Judaism, he writes of John Adams: “Jewish law was worse than just an exercise in squandered effort, Adams claimed—it was demonic. Referring to the two components comprising the Talmud, he lamented, ‘The Daemon of Hierarchical despotism has been at work both with the Mishna and Gemara.’”

As Porwancher notes, this sentence is from a letter Adams wrote to Thomas Jefferson on November 14, 1813. Reading the whole letter, however, it’s clear that the two former presidents were discussing Jefferson’s famous edition of the Gospels, then in preparation, in which he literally cut up the New Testament to extract what he believed to be Jesus’s original words and ideas. As Adams says, Jefferson was “selecting the Philosophy and Divinity of Jesus and Separating it from all intermixtures.” In this context, Adams observes that scholars have tried “explaining many passages in the New Testament, by comparing the Expressions of the Mishna, with those of the Apostles and Evangelists.”

He then complains that this kind of critical scholarship was made more difficult by the actions of Pope Gregory IX, who in 1238 was prompted by a renegade Jew, Nicolas Donin, to order the burning of all copies of the Talmud in Christendom. It is this act of destruction that Adams is referring to when he writes of the “Daemon” that “has been at work both with the Mishna and Gemara.” In other words, Porwancher’s reading of the phrase is the inverse of what Adams intended. He was lamenting not Judaic despotism but papal censorship, displaying an extraordinary familiarity with Jewish texts and history in the process.

Adams regrets the destruction of the Talmud because it makes it difficult to compare the Rabbis’ Aramaic with that of the Gospels and thus expose the way church authorities have misinterpreted Jesus’s egalitarian message. “How many proofs of the Corruptions of Christianity might We find in the Passages burnt?” he asks at the end of the letter.

This error doesn’t vitiate Porwancher’s argument, but it does suggest the role of Jews and Judaism in eighteenth-century culture was more nuanced than his book often conveys. Even so, students of American history will find that The Jewish World of Alexander Hamilton offers an interesting new perspective on some of America’s best-known figures, showing that in the early republic—as in so many times and places—Jews played an imaginative role far out of proportion to their actual presence.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

History with a Flourish

So much gets lost in translation—and to history—when household items, heavy with use, first assume the status of heirlooms and then land in museum vitrines, heralded as art rather than history.

Inventing American Judaism

Unlike the Jews of Venice, whose charter was anxiously renegotiated every decade or so, American Jews participated in civic life, confidently building themselves a future.

Jewish Destiny in a Cheek Swab

Possible Jewish ancestry has fascinated both Jews and non-Jews when it comes to American historical figures, reaching as far back as Alexander Hamilton.

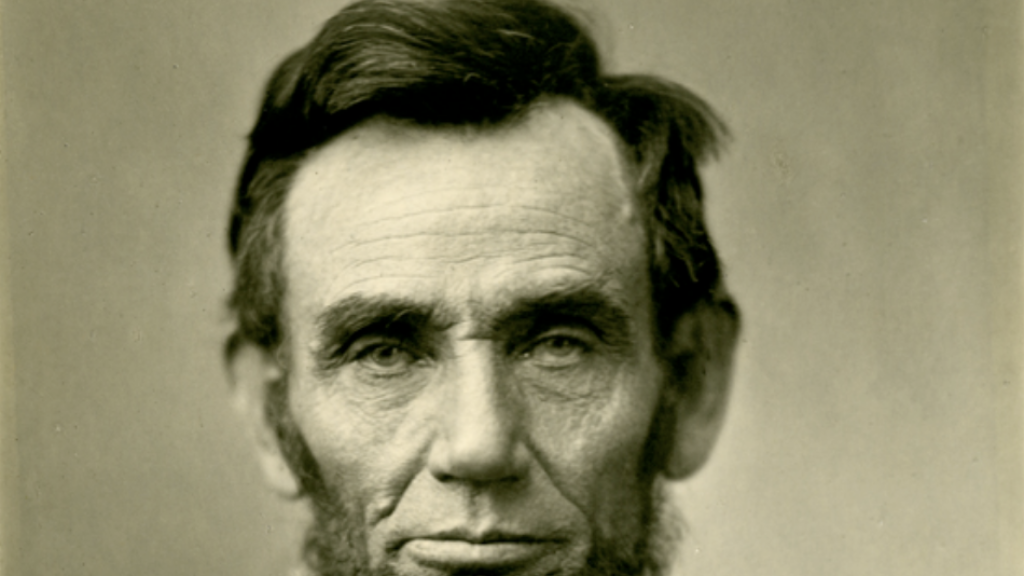

Was Lincoln Jewish?

Abraham Lincoln became a saint for American Jews. But was he also "bone from our bone and flesh from our flesh"? One rabbi thought so.

Chaim Shimon

The claim that Hamilton was Jewish rests on the supposed conversion to Judaism of Rachel Faucette, in order to marry Johann Lavien (to Porwancher, Levine). Questions in that regard:

What did 'conversion' mean in Nevis in the 1740s? -- Did the candidate study? Did a rabbi supervise the process? Did she go before a bet din? Or, as one might surmise without any real evidence, did Rachel simply say before a town magistrate that she a Jew, thus satisfying the problem of intermarriage to Lavien/Levine?

On that point, if a Christian and a Jew were planning to intermarry, why would the Christian go through the conversion process to Judaism? Wouldn't it be vastly more logical for Lavien/Levine to convert to the dominant and privileged religion of Christianity? Before you answer, let us remember that Mr. Lavien/Levine seems to have ignored perfectly well any hint of his being Jewish. To get married, he's suddenly a Jew?

The greatness of Alexander Hamilton is unique and enduring. ..even though the man (in my layman's guess) was absolutely not a Jew.

Kennyboy

Your commenter Chaim Shimon seems to be accepted as the ultimate expert. He wrote 11 days ago -- and nobody has had anything to say since.

Undaunted by Mr. Shimon's opinion, I put forth the following: If Hamilton's Jewish pedigree is fake news, how does this book get to be published at all? To me, 'John Levine' sounds very Jewish. America has had many great Jewish leaders and I am satisfied to learn that Alexander Hamilton was one of them.