The Natural at 70

In The Natural, America’s great baseball epic, the most revealing exchange comes near the end. In the movie, it happens after Iris (Glenn Close) stands in the bleachers to catch the attention of Roy Hobbs (Robert Redford), the slugger who plays the game with beautiful uncoached fluidity—that’s what it means to be a natural: neither scholarship nor schooling, just talent—who, in sunbaked August, has fallen into a slump. For a player, a slump is like amnesia. You forget who you are and where you live.

In the Bernard Malamud novel—in which Roy Hobbs is less Robert Redford than James Gandolfini, a behemoth who, in street clothes, looks more like an auto mechanic than a Greek god—it happens when Roy and Iris walk along the shore of Lake Michigan out near the Indiana Dunes. The moon hangs low on the water. Chicago lurks across the shipping lane. Roy has just told Iris his secret backstory. On the eve of his major league tryout, he went to the hotel room of a mysterious woman he’d met on the train to Chicago. Hobbs was great at nineteen, the scout’s dream of the brilliant hayseed at play on some midwestern sandlot. He was a hero, but a hero with a classic flaw—vanity. When he should have been minding his own business on the train, he was bragging to a stranger instead. When he should have been resting, he was heeding the call of that same strange mystery woman. When he enters the hotel room—this incident is based on the story of Phillies infielder Eddie Waitkus, who was shot by a lovestruck fan in Chicago’s Edgewater Beach Hotel in 1949—Roy is met by a woman, veiled and naked, who points a gun and asks: “Roy, will you be the best there ever was in the game?” “That’s right,” he replies:

She pulled the trigger (thrum of bull fiddle). The bullet cut a silver line across the water. He sought with his bare hands to catch it, but it eluded him and, to his horror, bounced into his gut.

Though he’s come all the way back from this early disaster, an itinerant journey that led from farm jobs and carnival work to the minor leagues, and has become the star for the surging New York Knights, it’s mostly regret that Hobbs feels: the waste of his youth, the failure to fulfill his potential.

“If I had started out fifteen years ago like I tried to,” he tells Iris, “I’da been king of them all by now.”

She sighed deeply. “You’re so good now.” “I’da been better,” he says. “I’da broke most every record there was.”

It’s the sensibility of the novel, and of Malamud, in a drop of rain. Looking back at his life, it’s not the accomplishments Roy sees—what he’s done—but what he could’ve done had it not been for misfortune. He blames fate without realizing that he’s made his fate. It’s only on the book’s last page, the most bitter end in sports literature, that he realizes he’s not especially cursed, that everyone has had the same bad luck, the only difference being how they responded—that character is destiny.

On the occasion of the novel’s seventieth anniversary, not long after the major league season was delayed by the same sort of owner-player squabbles that drive the book’s plot, at a time when a game that once functioned as an easy metonym for America is losing audience and relevance, I find myself returning to The Natural, which has always seemed the most American of Jewish novels and the most Jewish story in American folklore.

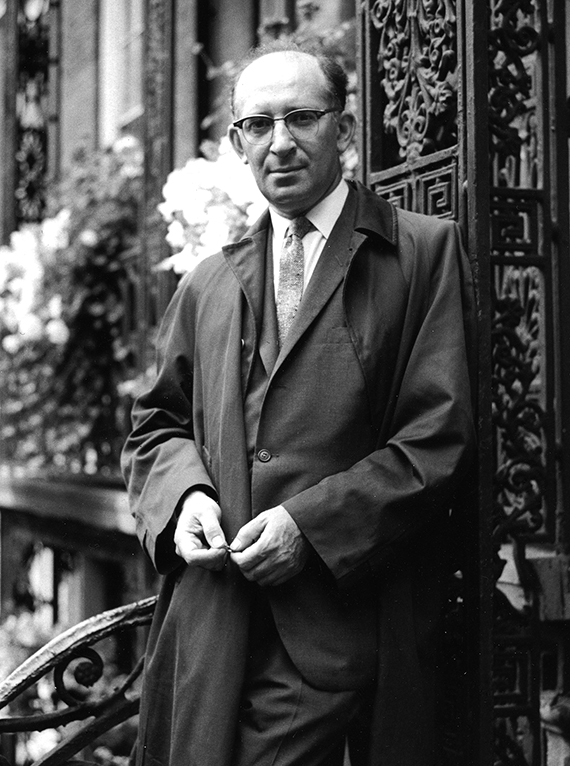

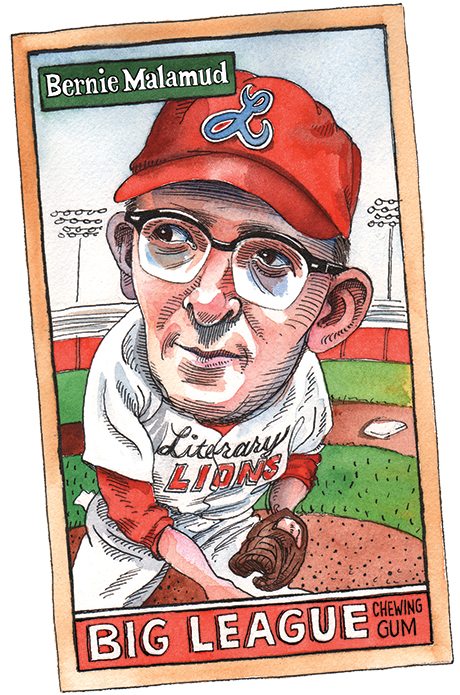

Start with its author, Bernard Malamud. A first-generation American, he was a product of his father’s stories about Russia, the haystacks and shuls and bleak little farms, as well as his own childhood in Brooklyn, which was stoops, corner stores, and elevated trains, steel wheels grinding. He attended Erasmus Hall High School, alma mater of Neil Diamond, Barbra Streisand, Mickey Spillane, and Bobby Fischer, then City College, that refuge of brilliant Jews quota-ed out of the Ivy League.

Born in 1914, Malamud, mustachioed and small, came out of college in the dim light of the Depression. His first jobs were teaching—four dollars a week to lead sixteen-year-olds through the modern canon: Hardy, James, Poe. He took a position at Oregon State College in Corvallis in 1949—about as far into Galus as a midcentury Brooklyn Jew could go. When not teaching freshman composition, he was writing, filling pages with visions of the Old World and Brooklyn. The stories on which much of his reputation rests began appearing in small literary magazines in the late 1940s and were eventually published in his first collection, The Magic Barrel, in 1958. Meanwhile, he was also working on a novel.

After burning a failed early attempt, Malamud published his first novel in 1952. It makes sense that he opened with baseball. Writing about the clubhouses, dugouts, and stadiums of 1930s New York was like writing about his childhood, the baseball-saturated city as it was before the war, when New York’s three great teams—the Yankees, who played in the Bronx; the Giants, who played in Manhattan; the Dodgers, who played in Brooklyn—were still in residence, each with its own history of heroes and curses.

The Yankees won the American League in 1936, when Malamud was twenty-two, with a lineup that included Lou Gehrig and Joe DiMaggio. The Giants, led by Mel Ott and Carl Hubbell, won the National League. The Dodgers, then managed by Casey Stengel—who played his first season two years before Malamud was born for a Brooklyn team led by Bill Dahlen, who, in 1891, played his first season alongside the Cubs’ Cap Anson, who played the game before there was a National League—finished seventh out of eight teams. It was a great chain of American tradition.

If you grew up in New York during the Depression, the game wrote a new novel every day. What’s more, by covering the national pastime, rewriting its myths, Malamud laid his claim to America itself. With The Natural, he was telling the world he was something more than just another brainy Brooklyn Jew. He was an American writer, made no less so by tribal affiliation. He was staking his claim same as Saul Bellow would do in the famous opening sentence of The Adventures of Augie March, published one year later: “I am an American, Chicago born.”

The plot of The Natural is simple. Roy Hobbs, who’d been shot by a “wacky dame” on the eve of his first pro tryout, has come all the way back to make his big league debut at thirty-five years old, ancient for a rookie. He dominates for half a season, leading his team to within a game of the World Series, before the temptations of the city—women, money—corrupt him, and he throws it all away and strikes out.

Malamud built the story around the game’s greatest stories, the common heritage of every fan. Roy Hobbs is a baseball Paul Bunyan, the kid who arrives from the sticks with a straw suitcase (like Mickey Mantle) intent on breaking every record (like Ted Williams). When the young Hobbs, who wears No. 9, same as Williams, expresses his ambition by saying, “Sometimes when I walk down the street I bet people will say there goes Roy Hobbs, the best there ever was in the game,” he is Williams saying, “All I want out of life, is that when I walk down the street folks will say, ‘There goes the greatest hitter that ever lived.’”

Working as a pitcher in his youth—Hobbs later moves from the mound to the outfield, just like Babe Ruth—he strikes out the Whammer, an aging star based on the Babe, defeating him with three straight pitches in a scene that recalls Ernest Thayer’s 1888 poem “Casey at the Bat,” which was itself based on the late-game antics of the sport’s first star, Mike “King” Kelly.

After his early failed attempt—the one that ended with his shooting—Hobbs is signed by the New York Knights, a fictional version of the pathetic Dodgers of the 1920s and 30s, the club known as Dem Bums. (Questioned on the Dodgers’ prospects, Giants manager Bill Terry asked a reporter, “Is Brooklyn still in the league?”)

Bump Bailey, the Knights’ best hitter, whom Hobbs must dislodge to earn a place in the starting lineup, is a trickster clown based on Babe Herman—the other Babe—who spent six seasons with Brooklyn. Though Herman hit .393 in 1930, he was seen as an error-prone buffoon whose bumbling was captured in the first sentence of John Lardner’s profile, which many consider the greatest lead in sports writing history: “Babe Herman did not triple into a triple play, but he doubled into a double play, which is the next best thing.” Bump’s tragic end—chasing a long drive, he runs into the center field wall and dies—is an homage to Brooklyn center fielder Pete Reiser, who, in his brilliant haste and hustle, collided with the wall over a dozen times during his career. In the course of ten seasons, he had to be stretchered off the field eleven times. Hobbs uses a homemade bat in The Natural—he calls it Wonderboy—same as the dead-ball era star Heinie Groh, who called his hand-tooled stick the “bottle bat” because, with a skinny shaft and fat barrel, that’s what it looked like. The abdominal distress that hospitalizes Hobbs late in the novel is a riff on the so-called bellyache heard round the world that kept Babe Ruth out for two months in 1925. (Attributed to a hot dog and beer binge, the famous bellyache was more likely a symptom of syphilis.)

The Natural is like a Chuck Close painting: a big picture made from little pictures. The little pictures are the details and anecdotes of folklore. The big picture is the game’s great scandal of 1919, when eight members of the White Sox—soon to be known as the Black Sox—took money from gamblers to throw the World Series.

In real life, when the news broke, a kid accosted Chicago star Shoeless Joe Jackson, who was walking with Happy Felsch, outside Comiskey Park, saying, “‘It ain’t true, Joe.’ The two suspected players did not turn back,” James T. Farrell reported in a Chicago newspaper. “The crowd took up the cry and more than once men and boys called out and repeated: ‘It ain’t true, Joe.’”

In the novel, what seems like the same kid hands Hobbs the newspaper, then, when Hobbs hands it back, says, “‘Say it ain’t true, Roy.’ When Roy looked into the boy’s eyes he wanted to say it wasn’t but couldn’t, and he lifted his hands to his face and wept many bitter tears.”

By the end of the novel, Malamud has given us a surreal vision of the game’s great story lines. First the corruption, the temptations of wealth and fame. Hobbs’s dream is corrupted because it’s the wrong dream—a quest for records is vanity. The legend of the shooting star is second, the player who burns bright for a season, then vanishes, because, as a coach says of flame-throwing pitcher Nuke LaLoosh in the movie Bull Durham, “He’s got a million-dollar arm but a five-cent head.” Even at peak performance, such a player—because no one can perform like that and last—is touched by doom, which makes it impossible to stop watching. Tony Conigliaro, who hit monster shots for the Red Sox until nearly being killed by a bean ball in 1967, or Mark “The Bird” Fidrych, the eccentric Tigers pitcher (he whispered to the ball, screamed at the mound) became a national sensation in 1976 before blowing out his arm in 1977—it was their incandescence that made their downfall seem inevitable.

The Natural was published on August 21, 1952, as the pennant race was heating up. The Giants were still in the hunt, but it was the Dodgers, led by Jackie Robinson, who’d win the National League before losing the World Series to the Yankees in seven games. The novel’s events seemed to echo the unfolding action—Mickey Mantle hitting a titanic home run in the eighth inning of Game 6 of the World Series was Hobbs connecting with Wonderboy; Casey Stengel, who’d switched from Brooklyn to New York, was Pop Fisher, the Knights’ desiccated skipper arrived at the perfect moment. The ballparks were still packed in 1952, the crowds still rambunctious. The intellectual fan having been hungry for a literature that took the game seriously, the book sold and sold. It was The Natural that made the rest of Malamud’s career possible.

Critical reaction was mixed. The New York Times gave the book little space, but the space it did give was all praise. Norman Podhoretz’s first piece for Commentary, the magazine he’d eventually take over, was a review of The Natural. Handing Podhoretz the galley, editor Elliot Cohen said something like, “Since you know something about both Brooklyn and baseball . . .” Podhoretz praised Malamud’s approach—“The Natural is the first serious novel we have had (after Ring Lardner’s You Know Me Al) about a baseball player”—but questioned his prose, which he considered overripe and portentous:

The habit of symbolizing everything, from baseball bats to men and women, and of multiplying allusions to the point where they begin to crowd out reality altogether, is one of the more unfortunate legacies bequeathed by Joyce and Eliot to contemporary writers.

According to academics, especially those who have taught the novel at the college level, the plot of The Natural is based on the legend of the Fisher King, the wounded monarch in search of the Holy Grail. The king is old and feeble, and his land is overcome by drought. Redemption comes with Perceval, the knight who carries a magical sword, which, according to prophecy, will break at a key moment. The legend was in the air in Malamud’s formative years. Richard Wagner based Parsifal on the legend, which also supplied the structure for T. S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land.” Hints of it turn up all over The Natural. It’s in the woeful team at the center of the action, which is led by a broken baseball king named Pop Fisher. When Hobbs appears to save Pop Fisher and his club, he, too, carries a magical sword that shatters in the clinch. (“Wonderboy lay on the ground split lengthwise, one half pointing to first, the other to third.”)

The city, like the team, is in the midst of a drought when Roy arrives. His first hit is met by a crack of thunder (“a noise like a twenty-one gun salute”) then a downpour of rain. (“By the time Roy got in from second he was wading in water ankle deep.”) Within days of his first appearance in the lineup, the outfield grass, which had been parched, is lush and green. When Roy is down two strikes with a man on third, “it felt like winter.” The Fisher King and his disciples had been in search of the Holy Grail. Pop Fisher and his boys—the New York Knights!—are in search of the National League pennant, which was the only grail most Brooklynites cared about in 1952.

And yet, although I agree that the structure of Malamud’s novel is the Grail Legend and that its settings, characters, and anecdotes are baseball lore, its sensibility is Jewish. The Knights’ desiccated kingdom is not Britain or New York. It’s Jerusalem. Roy Hobbs is not Perceval. He’s David, whose thrown stone was a split-finger fastball. As in the temple era, the path to redemption must be cleared by sacrifice. In this case, it’s Bump Bailey, who chases a fly ball from this world to the next. The final battle does not take place on the field but in the heart of one man, Hobbs, who, same as Jacob, wrestles the angel till his hip aches. As in the War Scroll currently on display in the Israel Museum, it’s the sons of light (win the game and walk away poor but righteous) against the sons of darkness (throw the game and walk away damned but rich).

And the bat?

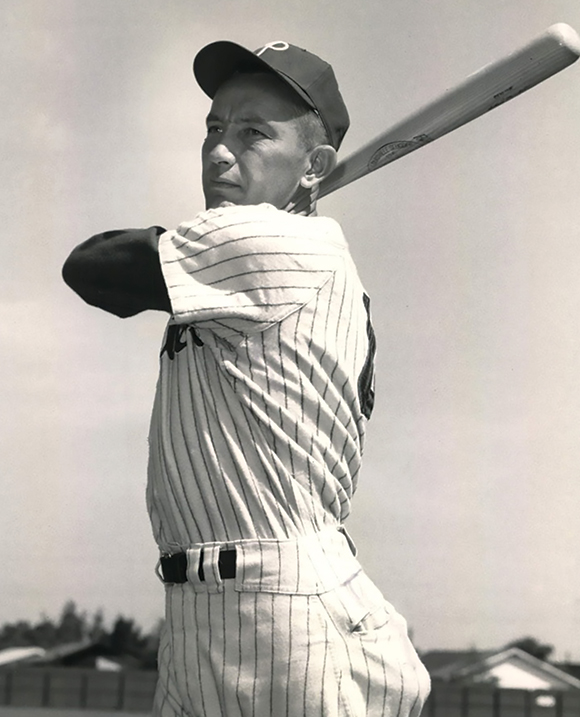

It’s not Excalibur. It’s the Staff of Moses. Some even say that Hobbs himself was Jewish, like Hank Greenberg, Sid Gordon, or Al Rosen. It’s a suggestion based on one sentence that appears late in the book, a sentence that sounds like a signal sent on a frequency only Jews will receive: “[Hobbs] considered fasting but he hadn’t fasted since he was a kid.”

Malamud became increasingly focused on Jews and the Jewish condition as his career progressed. It’s as if he took that first faint signal, tuned it in, and amped it up. The Assistant, The Fixer, The Tenants—Jews, Jews, Jews. On the first page of his first novel, Hobbs, who like Malamud was getting to the big leagues late (Malamud was thirty-eight when The Natural was published), is striking a match in the darkness. On the last page of his last novel, God’s Grace, published in 1982, mankind has been erased from the earth, and only a few primates, taught to talk by Calvin Cohn, who’d been the last human, carry on the tradition. “In a tall tree in the valley below, George the gorilla, wearing a mud-stained white yarmulke he had one day found in the woods, chanted, ‘Sh’ma, Yisroel, the Lord our God is one.’”

The Natural was adapted for film by screenwriter Roger Towne, who remade its sensibility from midcentury Brooklyn Jew to modern Hollywood. Everyone assumed that Malamud would hate it. The reviewer David Thomson dismissed it as “poor baseball and worse Malamud.” Hobbs, who is big, rough, and weird in the book, becomes dignified Robert Redford in the movie. (As they say, write Yiddish, cast British). The sounds of New York—the hecklers and horns—are replaced by Randy Newman’s surging soundtrack. The novel’s bleak last page—Roy silently hands the paper boy back the newspaper with the headline “Suspicion of Hobbs Sellout,” then cries those “many bitter tears”—makes way for a Hollywood ending. Instead of selling out and then striking out, Hobbs hammers the ball into the stadium lights, sparks showering down, light defeating the darkness.

Malamud “went with his daughter to see the film,” the director Barry Levinson told sportscaster Bob Costas. “And she said afterwards, ‘So, Dad, what do you think?’ And he said, ‘At last, I’m an American writer.’”

Suggested Reading

The Symbol Catcher

My friends and I took for granted that the connection between the cards and the players they represented wasn’t just arbitrary.

The Rise of Hank Greenberg

On Rosh Hashana, Greenberg went to shul, then the ballpark and hit two home runs. "Hank’s Homers are strictly Kosher," said the Detroit Free Press.

The Jewbird

It is in his stories, rather than his novels, that Malamud emerged as a unique writer. A new series brings new exposure to both.

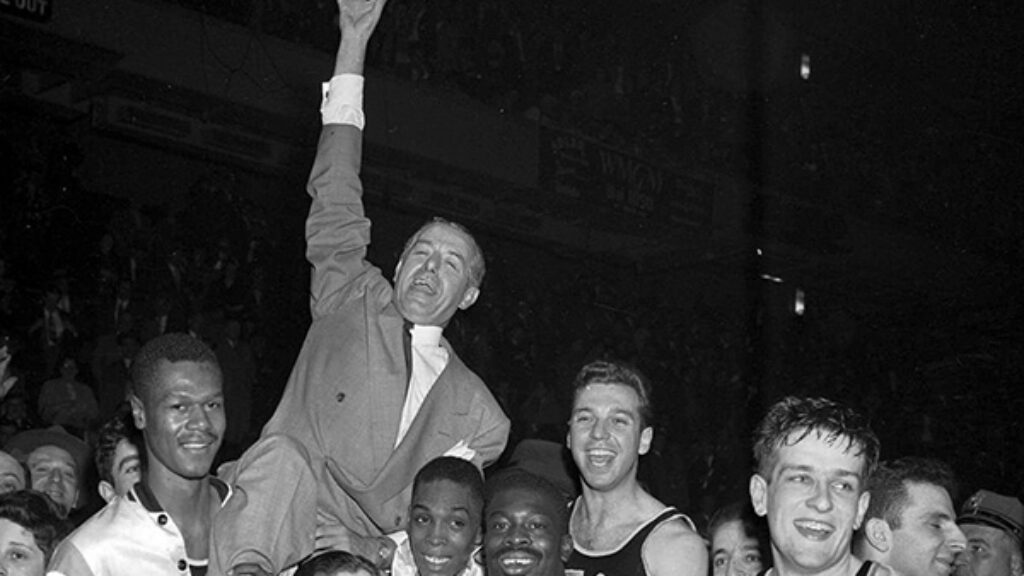

The Fix Was In

The 1951 basketball game that pitted CCNY, which fielded blacks and Jews, against the all-white University of Kentucky seemed less a meeting of schools than a clash of civilizations: old versus new, South versus North, prejudice versus tolerance.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In