Lincoln and the Jews

The Civil War is, even now, the most important event in American history, but it is one to which fewer and fewer Americans can claim a direct familial connection. If your ancestors came to this country after 1865—if your background is Italian or Greek, Puerto Rican, or Korean—then you probably have no relative who took part in the struggle over America’s destiny. But does this mean that you are less connected to American history than if your forebears wore Union blue or Confederate gray? Are you less susceptible to the “mystic chords of memory” of which Abraham Lincoln famously spoke in his first inaugural address? Only a mind immune to the power of historical imagination could answer yes.

The Civil War continues to make a double claim on the memory of every American, regardless of when his or her family became American. The first is that the issues about which the war was fought—slavery and sectional division—continue to define American society and politics to this day. It’s impossible to make sense of quite a few daily headlines or election results without knowing about the Civil War’s causes and consequences. Second, and even more important, is that at a distance of 150 years, no American can claim any living memory of the war. To possess it imaginatively today requires the work of reading and thinking, which are open to anyone, regardless of ancestry. To say otherwise is to deny the very premise of America, which is that it is a country founded not on blood but on an idea of freedom.

For American Jews, the question of our relationship to the Civil War is complex. On the one hand, the vast majority of American Jews are descended from Eastern European immigrants who arrived here after 1880, and so they have no ancestral connection to the war. At the same time, as Jonathan D. Sarna and Benjamin Shapell amply demonstrate in Lincoln and the Jews, there was a sizable number of Jews in America in the mid-19th century—some 150,000 by the time Lincoln was elected president in 1860, many of them recent immigrants who fled Germany in the aftermath of the failed revolution of 1848. This was a small fraction of the nation’s population, then 31 million, but it means that if we look for Jewish connections to the Civil War, we will find plenty of them. Jews fought and died on both sides of the conflict, at ranks from private to general; they served in government in the North (two Pennsylvania congressmen were Jews) and in the South (Judah P. Benjamin, a former U.S. senator from Louisiana, was the Confederate secretary of state).

This means that Lincoln and the Jews is a less unlikely conjunction than it might first appear. It cannot be said that Lincoln spent a great deal of time thinking about Jews or Judaism, or that Jewish questions formed a significant part of the politics of the period. But Sarna and his coauthor Shapell, a Civil War collector who provided many of the documents and artifacts that illustrate it, show that Lincoln encountered a surprising number of Jews throughout his life. Lincoln and the Jews is largely a catalogue of the American Jews whose paths happened to intersect with his, from his early career in Springfield, Illinois to his years as president and commander-in-chief. Throughout, he seems to have treated them with the benevolence and absence of prejudice one would expect from the Great Emancipator. As Sarna summarizes on the book’s last page: He “interacted with Jews, represented Jews, befriended Jews, admired Jews, commissioned Jews, trusted Jews, defended Jews, pardoned Jews, took advice from Jews, gave jobs to Jews, extended rights to Jews . . . His connections to Jews went further and deeper than those of any previous American president.”

Lincoln’s philo-Semitism is especially notable in contrast to his fellow politicians and his own generals. Lincoln and the Jews reproduces a number of letters in which such figures refer to Jews, almost always with a sneer—as when George McClellan, Lincoln’s battle-shy general and later rival in the 1864 presidential election, finds himself on board a ship unfortunately full of “the sons of Jacob.” Exactly why Lincoln was immune from this conventional prejudice is cause for speculation. Perhaps it is because he grew up in rural Kentucky and Indiana, areas with no Jewish population, and so gained his earliest impressions of Jews from the heroic accounts of the Bible, with which he was deeply familiar. (Sarna notes that the Protestant denomination in which Lincoln was raised believed in predestination and was thus indifferent to efforts to proselytize Jews.)

Lincoln met his first real-life Jews in the mid-1830s, when he moved to the Illinois capital of Springfield to serve in the state legislature. They tended to be small businessmen, clothing retailers, or department store owners, whom he encountered as neighbors, constituents, and legal clients. While nothing in particular is known about his relationships with men such as Louis Saltzenstein, a postmaster whose store the young Lincoln patronized, or Julius Hammerslough, from whom Lincoln bought some suits, such acquaintances show that Lincoln was accustomed to dealing with Jews on familiar terms.

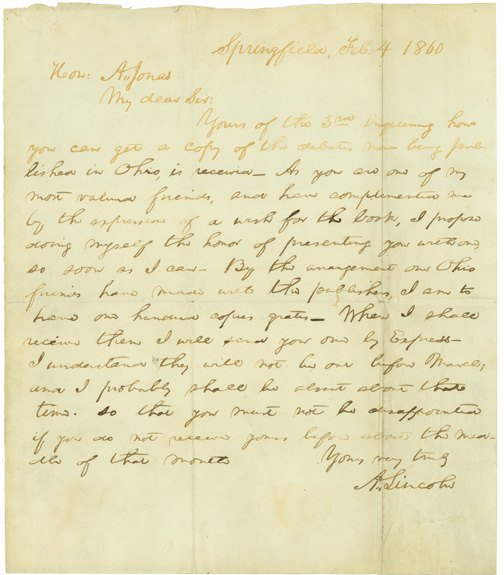

In one instance, Sarna shows, there was something more like real friendship. Abraham Jonas was, like Lincoln, a lawyer and politician who became an activist in the newly founded Republican Party. Jonas, it seems, was not especially religious—“on at least one occasion in 1854 he dined openly with Abraham Lincoln and others at an ‘oyster saloon’”—but he was well known as a Jew in his small town of Quincy, Illinois. The two Abrahams probably met in 1843, at a Washington’s Birthday event in the state capital, and soon Jonas became Lincoln’s political ally. Jonas hosted Lincoln during his statewide tour in 1858 for the Lincoln-Douglas debates and later boosted his candidacy for president. After Lincoln was elected, Jonas reaped his reward in patronage, getting a job as postmaster in his hometown of Quincy. While the two men do not seem to have been especially close—surely Lincoln had many political friends like Jonas—the relationship did help to contribute to Lincoln’s view of Jews as equal citizens and ordinary Americans.

Interestingly, Sarna notes that Jonas urged Republican leaders to earn favor with Jewish voters by blasting the inaction of the Buchanan administration over the Mortara Affair. This was the notorious case in which a young Italian-Jewish boy who had been baptized without his parents’ knowledge was subsequently abducted from his home and held by Catholic authorities who refused to return him to his family. “In the free states,” Jonas wrote to Illinois’ Senator Lyman Trumbull, “there are 50,000 Jewish votes, two thirds of whom vote the democratic ticket,” but a strong stand on the Mortara Affair might win them over to the Republican side. This may have been the first time in American politics that a strategist talked about courting the “Jewish vote,” which, small as it was, could have been significant in a closely contested election.

Lincoln’s personal friendships with Jews did not lead the majority of Jewish voters to support him in 1860. Some German-Jewish immigrants, who had fled their home country on account of their liberal politics, continued to fight on the side of progress and anti-slavery, becoming Republican stalwarts. But the majority of Jews lived in eastern cities that were Democratic strongholds, and the involvement of many Jews in the clothing trade led them to fear the disruption of cotton imports should the South secede. (There was also, perhaps, though Sarna doesn’t speculate on it, a certain inherited fear of social disruption: Historically, civil wars and ideological strife had boded ill for Jews in Europe.)

Nor, as Sarna points out, were American Jews necessarily opposed to slavery. Though the experience of slavery and emancipation stands at the heart of Jewish history, rabbis could be found who justified the institution—andnot just in the South. Sarna introduces the reader to Rabbi Morris Raphall of New York’s B’nai Jeshurun, who devoted his sermon on January 4, 1861—which had been declared a national day of fasting by President Buchanan—to a biblical defense of slaveholding. Isaac Mayer Wise was unimpressedby Lincoln and appalled by the crowds that gathered in Cincinnati to greet the president-elect on his way to Washington, comparing them to Philistines worshiping their god Dagon.

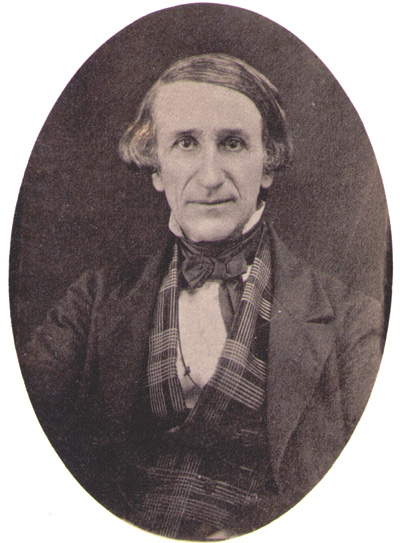

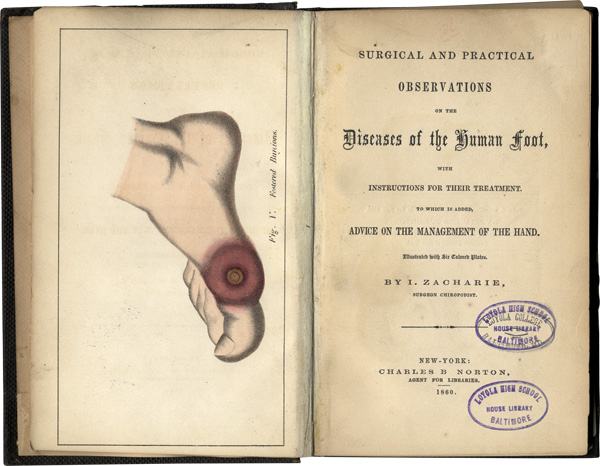

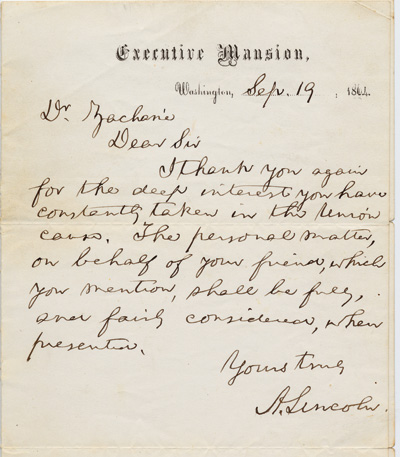

As president, Lincoln had to pass judgment on many issues involving Jews, from appointments and promotions to cases of desertion. Sarna and Shapell chronicle all of these, no matter how minor, and show that Lincoln always acted generously and without prejudice. While General Benjamin Butler was writing about Jewish smugglers, “They are Jews who betrayed their Savior; & have also betrayed us,” Lincoln proclaimed to a visitor, “I myself have a regard for the Jews.” He even extended this regard to a character like Issachar Zacharie, the most colorful figure to appear in Lincoln and the Jews. Zacharie, a chiropodist and con man, managed to use his foot-doctoring skills to win the president’s confidence, whereupon he was entrusted with secret diplomatic missions to the South. Alas, Zacharie’s dream of establishing an Army podiatric corps came to nothing, even though Lincoln took time out of his frenzied schedule to give him not one but three handwritten testimonials.

There was only one occasion during the Civil War when the treatment of Jews actually posed a serious policy and political issue for Lincoln. This was in December 1862, when Ulysses Grant issued his notorious General Order No. 11, expelling “Jews as a class” from the territory under his command, from Mississippi to Illinois. It remains the most famous act of official anti-Jewish discrimination in American history. Sarna, who has previously devoted a book to the affair, points out that Grant’s pique had a personal source. His own father had entered into partnership with some Jewish merchants who hoped to take advantage of the family connection to get a permit to purchase cotton in Grant’s territory. When Grant banned Jews from his department, it was less out of religious bigotry than from the widespread belief that the merchants who traveled to war zones for the purpose of commercial speculation were mostly Jews—as indeed many were, just as many Jewish businessmen served the Union Army as sutlers and quartermasters.

It is a sign of Lincoln’s good nature and sense of justice that, as soon as he heard about Grant’s impetuous order, he ordered it revoked. Legend has it that when one of the Jewish expellees, Cesar Kaskel, came to the White House to seek Lincoln’s help, he used biblical language: “we have come unto Father Abraham’s bosom, asking protection.” “Whether or not such a conversation actually took place,” Sarna writes, General Order No. 11 was immediately countermanded. Soon after, a delegation of Jews came to Washington to thank the president, who told them that he would permit “no distinction between Jew and Gentile.”

Such acts of benevolence helped Lincoln to win the support of many Northern Jews who had initially opposed his election. And when the president was assassinated, the outpouring of grief from Jewish Americans was intense. As Sarna notes, the day Lincoln was shot—April 14, 1865—was a Friday, which meant that the next day was Shabbat. As the news of his death early Saturday morning spread across the country, rabbis were the first clergymen to eulogize the president. As one Jewish observer noted, “it was the Israelites’ privilege here . . . to be the first to offer in their places of worship, prayers for the repose of Mr. Lincoln.” Some congregations spontaneously offered a Kaddish prayer for Lincoln, an unprecedented gesture for mourning a Gentile.

If, in fact, he was a Gentile: Isaac Mayer Wise, who had disdained Lincoln in 1860, declared in 1865 that “he supposed himself to be a descendant of Hebrew parentage,” “bone from our bone and flesh from our flesh.” Call it the madness of grief, but this desire of Jews to claim Lincoln for their own was a way of demonstrating that being American and being Jewish could be complementary parts of the same identity. To this day, American Jewish life rests on that same promise.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

In Pursuit of Wholeness: The Book of Ruth in Modern Literature

While not the most dramatic of all the biblical stories, the quietly moving book of Ruth, which we read on Shavuot, continues to resonate in Western literature.

Zion and Party Politics, 1944

In the summer of 1944 support for Zionism was transformed from a low-risk political gesture to a bona fide election issue. FDR was not pleased.

The Best Revenge: A (Qualified) Case for Hunters

“I need an army,” the American Nazi says, “hundreds of ignorant white men looking for someone to blame.”

Satmar, American-Style

The explosive growth of Satmar Hasidim has shocked and worried many who see their culture as un-American. But two new books argue it was only in America that the sect could have flourished at all.

Jacob Arnon

Why does a book aimed at exploring President Lincoln's relationship to the Jewish people in the US describe what some Rabbi thought about slavery or another person's impressions about people cheering him:

"Isaac Mayer Wise was unimpressedby Lincoln and appalled by the crowds that gathered in Cincinnati to greet the president-elect on his way to Washington, comparing them to Philistines worshiping their god Dagon."

There certainly were many more non Jewish clergyman preaching about the "justness of slavery."

The point is to explore why a President was so benignly disposed towards the Jewish people. It is this that makes the head of State so unique among country leaders in the mid 19C.

No people is perfect and the mea culpas included in the book is merely meant to sensationalize.