The Novelist and the Physicist

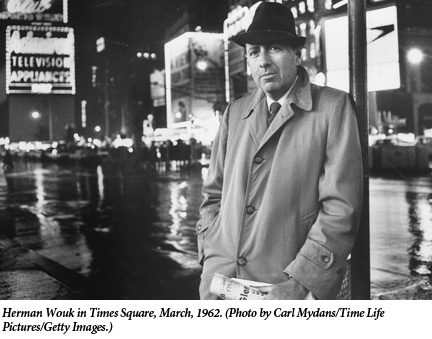

Whatever one thinks of Herman Wouk as a fiction writer—and professional views have generally tilted against him—his fecundity and popularity are unassailable: twelve novels over sixty-three years (four of them emerging since he turned 69), two apologias for Judaism, four plays, and some fictional trifles. All told, he has sold nearly forty million books, and virtually all of his works are in print.

In the 1950s, Wouk produced the three works that made his reputation. The Pulitzer Prize-winning The Caine Mutiny sat atop the Times’ list for nearly two years and took on the charged Cold War issue of the rights of authority vs. those of personal conscience, finding for authority. Marjorie Morningstar, another commercial blockbuster, loosed Dickens on the Jewish Upper West Side of the mid-1930s and established that bourgeois ways and mores were darkly amusing but more conducive to the good life than those of Bohemia. The novel was also the first, as Norman Podhoretz pointed out in an otherwise scorching review in Commentary, “to treat American Jews intimately as Jews without making them seem exotic.” And, finally, with the somewhat pugnacious This Is My God: The Jewish Way of Life, Wouk entered into the lists of Judaism’s post-war explicators.

Among his many other works, the World War II novels of the 1970s stand out. The Winds of War and War and Remembrance comprise a 2,000-page, million-plus word apprehension of World War II, brimming, like their avowed model War and Peace, with reverently reconstructed battles, madly intersecting fates, and scores of characters, historic and imagined, who witness all that requires witnessing. Wouk’s next four novels—the last of which appeared in 2004—did not enjoy the extraordinary commercial success of his earlier work (or the serious attention of critics, which Wouk may have counted a good thing), but they sold well enough, while continuing to take on big topics: the Nixon White House; the place of Jews in a pluralistic democracy; the history of the State of Israel; and the science and politics (and romance) of particle physics. And now, in his mid-90’s, Wouk has published The Language God Talks, which aims to elucidate the complex and fraught question of whether religious faith and science can live in peace.

Although it has recently been rendered current by crusading school boards, cable television’s best minds, and opportunists of all varieties, the question is not new, dating back at least to Philo’s 1st-century attempt to conjoin Genesis and Plato. The question bloomed in a public way, of course, in early modern times, in the literal and figurative trials faced by Copernicus, Darwin, and John Thomas Scopes, and it flourishes today in conference proceedings, campaign speeches, and yards of trade books. One opens The Language God Talks, therefore, wondering what Wouk, certainly a prodigious explicator and street-corner moralist, but no scientist or theologian, could contribute to a discussion already so ripe.

From a structural perspective, the answer turns out to be a charming, if rambling, and occasionally disjointed, essay. The Language God Talks is a personal and literary memoir, but it also includes nimble explications of cosmology, astrophysics, and Jewish learning, along with sharply-drawn miniatures of some of the great and odd beings upon whom science seems to depend for its progress. These include the superstar physicist and legendary know-it-all Murray Gell-Mann, whom Wouk at one point tries to engage in conversation on science, and whose “responses, while not impolite, hinted that an orangutan was getting a bit too familiar.

The core of the book is made up of Wouk’s recollections of his meandering intellectual friendship with the brilliant, charmingly caustic atheist-Jewish physics laureate Richard Feynman, and their stop-and-start debate as to the purpose, or lack thereof, of the universe. This brings us to the book’s modest but welcome contribution to the 2,000-year-old discussion: a convincing depiction of a sharp quarrel on a matter of infinite cultural and personal importance between two men who never sacrifice the respect due to an honest interlocutor. The argument between Wouk and Feynman was triggered when Wouk, doing research for War and Remembrance, interviewed Feynman about the Manhattan Project. At the conclusion of the interview Feynman chided him, “You had better learn [calculus]. It’s the language God talks.”

The core of the book is made up of Wouk’s recollections of his meandering intellectual friendship with the brilliant, charmingly caustic atheist-Jewish physics laureate Richard Feynman, and their stop-and-start debate as to the purpose, or lack thereof, of the universe. This brings us to the book’s modest but welcome contribution to the 2,000-year-old discussion: a convincing depiction of a sharp quarrel on a matter of infinite cultural and personal importance between two men who never sacrifice the respect due to an honest interlocutor. The argument between Wouk and Feynman was triggered when Wouk, doing research for War and Remembrance, interviewed Feynman about the Manhattan Project. At the conclusion of the interview Feynman chided him, “You had better learn [calculus]. It’s the language God talks.”

Though he had long expressed more traditional views regarding the Holy One’s locutions, Wouk found Feynman impressive. Eventually, he took up calculus, first with the aid of a self-help book, then with a tutor, and finally in a high school class that proved too demanding. Offering a few lame words of encouragement to his teenage classmates, the “defeated, departing old codger,” Wouk writes, exited the classroom to “a sympathy hand.”

Wouk never returned to calculus, but he met Feynman again at the Aspen Institute in the summer of 1973, where the two men walked the mountain trails. They talked about science, Talmud, literature, history, and other matters that brought pleasure to both of them, if not agreement. Wouk took notes, as he seems to do on almost every occasion, and considered writing a book about their conversations. But he put it off, and in fact never saw Feynman again. The Language God Talks ends, in what reads like an act of longing, with one last fictional meeting set in Washington, D.C., where Wouk lived for many years, and where Feynman has come for medical treatment shortly before his death of cancer in 1988. They walk the city together while reprising some of the themes they had taken up in Aspen, in particular the matter of faith and science.

Wouk, who has been rightly charged with thumbing scales to get his fictions to come out right—Isaac Rosenfeld said that he wrote like “a man [playing] chess against himself”—engages in no such cheating here. Though weakened by illness, “Feynman” remains Feynman, interested in Wouk’s religious views, but convinced as ever that, as he once said in a television interview: “It doesn’t seem to me that this fantastically marvelous universe, this tremendous range of time and space and different kinds of animals, and all the different planets, and all these atoms with all their motions, and so on, all this complicated thing can merely be a stage so that God can watch human beings struggle for good and evil—which is the view religion has. The stage is too big for the drama.”

At the conclusion of their imagined conversation, as they near the steps of the Georgetown University Medical Center, Wouk plays his final hand, pressing Feynman on the anthropic principle. This is the principle some physicists have invoked to explain why the constants of nature seem uniquely calibrated to evolve and foster life. What is this if not precisely the possibility, even the probability, of a God-constructed stage? Feynman counters impatiently: “Yes, yes, I know that flight of fancy. It completely loses me.” And a moment later the argument is over, with Wouk calling out “Teiku!“—an Aramaic word that, as Wouk explains, the Talmud uses to end irresoluble disputes. “I’ve enjoyed myself,” Feynman responds, and the reader, who has shared in the enjoyment, believes him.

Nonagenarian authors are certainly entitled to sympathy hands, but this slight book’s agile prose and good humor justify real respect. Wouk, however, doesn’t seem to be hanging around for the notices. The book’s publicity kit pointedly notes that he is currently at work on a novel. A recent videotape of him during a rare public appearance at the 2010 Los Angeles Times Festival of Books offers every indication of vitality. Wouk remains the relaxed, broad-browed, gravelly-voiced Bronx sage—Uncle Herman at the family table—telling practiced tales and deftly cracking wise about large topics to the delight of his audience, and his own considerable pleasure.

Suggested Reading

The Jewbird

It is in his stories, rather than his novels, that Malamud emerged as a unique writer. A new series brings new exposure to both.

From the Middle to the End

A deceptively simple novel about a suburban, Midwestern Jewish family catapults into something annoyingly profound.

The Jewish Critic and the Devil’s Point of View

We have never met this Mendele before, but he expects us to trust him, appreciate his wit, catch his references, and share his attitudes. In a few deft lines, the author created a figure so democratic you don’t have to look up to him, so familiar you don’t have to fear him, and so appealing you won’t realize you’re being flogged.

Tattooing God’s Name, a Jewish Adventure Out West, and Ultra-Orthodox Voting Patterns

A round-up of three new and notable articles in Jewish studies.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In