The Yiddish-Speaking Hitmen’s Union

In the American Jewish imagination, Jews in the Old World were all chaste and innocent and only learned to be bad once they arrived in the United States. Jewish gangsters like Meyer Lansky, Bugsy Siegel, Brownsville’s Murder Incorporated, and Detroit’s Purple Gang, among many others, are still remembered in historiography, fiction, and film, but that they had predecessors in the Old World is not. Szczepan Twardoch’s newly translated novel, The King of Warsaw, about a Yiddish-speaking hitman with a side hustle as a professional boxer, then, is not just a good read but a welcome reminder of the full range of Jewish life in interwar Poland. Of course, part of our determined forgetfulness is because that world was destroyed by the Nazis, and we would prefer to remember rabbis, scholars, artists, businessmen, and politicians than those on the opposite end of the spectrum: beggars, bums, imbeciles, crooks, gamblers, and murderers. This is as true of the great majority of Jewish historians as it is of a nostalgic, pious public.

So, what are we to make of Twardoch, a non-Jewish Pole who has written a crime novel featuring a volatile Jewish gangster who, among many, many brutal and nefarious acts, slices and dices a fellow Jew? Will there be complaints from the cultural appropriations department of the Jewish communal trust? Perhaps. Though if Jews are to take their history and literature seriously, then they should be able to accept Jews of all kinds in historical and literary works, from the best to the worst. Moreover, if the product is good, it shouldn’t matter who’s writing. If anything, Twardoch should be thanked for delving into the lower depths of Jewish gangland because he has made aspects of interwar Jewish Warsaw come brilliantly alive. The last time a Jewish crime story reached the heights of Polish bestseller lists was in 1933, when Urke Nachalnik, the nom de guerre of yeshiva-boy-turned-gangster Yitzkhok Farberovitsh, published his jailhouse memoir. The book was so popular, it won him early release from prison.

The King of Warsaw tells the story of Jakub Szapiro, a longtime boxer for Warsaw’s Maccabi sports club whose day job involves various gangland exploits, among them extortion and murder, the latter of which is described in cinematic, Tarantinoesque colors. Twardoch paints violence more than writes it. His book is mottled with with vivid accounts of brutality and bloodshed. His main partner in crime is fellow gangster and Polish socialist agitator Buddy Kaplica, with whom he shakes down store owners, murders debtors, visits brothels, and battles fascists. Both gangsters are surrounded by a lush panorama of characters who range from the wholesome to the grotesque and include a perverse, assimilated Jewish former Polish military man, a monstrous mafia goon with a parasitic twin, and a hooker with a heart of steel—and all of them perambulate among a truly compelling supporting cast. Take, for instance, “rat-faced, skinny little Munja”:

He was swarthy and dark-haired with a black mustache. Most people took him for a Gypsy and he had slightly Asian features, although Munja himself said he was a Jew, a little Polonized and assimilated, but a Jew. He was born in Harbin, he came to Poland in 1925, and supposedly he knew Chinese.

Yet for all that, he didn’t know Yiddish, he didn’t follow the traditions, and was notorious for pulling out a knife in a fistfight, and shooting a pistol in a knife fight. . . . He smoked like a chimney and had an ugly mustachioed wife who frightened him more than Kaplica, so he showed up at home no more than once a week.

Cleverly structured, Jakub Szapiro’s story is told from the perspective of a washed-up Israeli general he had taken under his wing as a boy, who taps out his memoirs on a rickety typewriter in Tel Aviv. Twardoch’s stylized prose is compelling: amid flashes of violence, he frequently interjects historical and philosophical ruminations. This allows the violent action to recede to the background as the reader ruminates with the writer about ideology or historical truth before being thrust back into a melee of fists and knives.

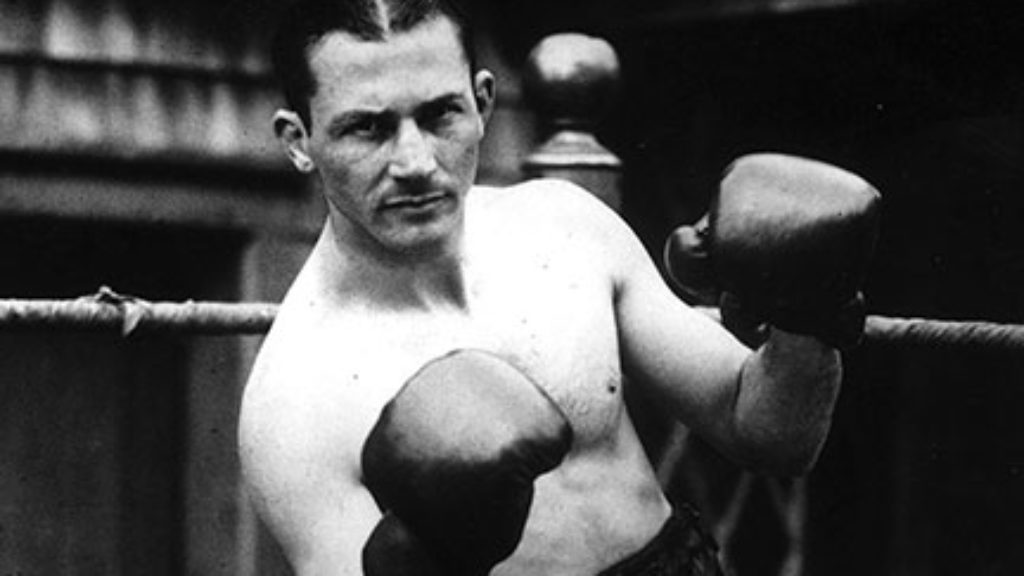

Twardoch appears to have been inspired by Jerzy Rawicz’s 1968 book, Doktor Lokietek i Tata Tasiemka (Doctor Lokietek and Papa Stripe), a history of political/socialist gangsters in interwar Poland. There also appear to be bits of famed Polish-Jewish boxing champion Shepsl Rotholtz in Jakub Szapiro, and more than a bit of Rifka Linderboym, the famed Warsaw madame, in Ryfka Kij, Szapiro’s ex-lover and sometime partner in crime.

Indeed, Twardoch has an uncanny ability to pluck real-life events and people out of history and slot them into his fictional depictions of gangland Warsaw in 1937. Some of these are major characters and plot points, but others are simple throwaways most readers won’t grasp, such as a quick joke about Rabbi Tzvi Yekhezkl Mikhlzon (the Plonsker Rov, a major rabbinic figure in Warsaw) or the brief mention of the 1937 arrest of a Betarnik in Jerusalem for blowing the shofar at the Kotel on Yom Kippur, which was genuinely reported as a two-sentence blurb in the middle of page three in the September 16, 1937, issue of Nasz Przeglad, Warsaw’s Polish-language Jewish daily newspaper.

These are details only a historian would notice, but Twardoch’s research has paid off. He manages to create a truly believable simulacrum of interwar Warsaw, its streets, its clattering markets, its whorehouses, its upscale restaurants, and its denizens—Jews and Poles of all persuasions—all of which sucks the reader into an atmosphere in which Jewish and Polish Warsaw abutted one another, were intertwined, and yet were also completely separate. He doesn’t shy away from depicting harsh Polish antisemitism but does avoid the tangled thicket of religious culture because this story is one of secular Jews, though they are certainly not entirely denuded of tradition. Moreover, Twardoch is completely dedicated to his characters. He is never done with exploring their personalities—at least not until he kills them off.

Sean Gasper Bye’s translation is solid and provides a fine narrative flow, although I do have a few quibbles, mostly boxing related. A boxer enters and exits the ring wearing a “robe,” not a “gown”—a small error but jarring to a fan. Also, the local gym where Szapiro coaches is called “Star” (Gwiazda). While an accurate translation, it prevents the reader from knowing that the Gwiazda Gym was owned by the Left Labor Zionists, who had the best Jewish boxing club in Poland during the 1930s. This becomes important when Twardoch introduces Szapiro’s brother, a staunch Labor Zionist who tries to convince his gangster brother to immigrate to Palestine.

A related matter, though not the fault of the translator, is the name of one of the main characters, Ryfka Kij (pronounced “Rifka Kee”). It’s likely Twardoch discovered this character and her famed brothel in Jerzy Rawicz’s book, where she is known as “Ryfka de Kij,” which, to the uninitiated, vaguely sounds as if it could be a Dutch or a Danish name. Twardoch shortened it to “Ryfka Kij” but doesn’t tell the reader where it comes from. It’s actually the nickname of a real person from Warsaw’s Jewish underworld: “Rifke di ki,” or “Rifka the Cow” in Polish-Yiddish dialect. A notorious Warsaw madame, her real name was Rifka Linderboym. Together with her son, Khatskel, she was involved in human trafficking and ran some of the city’s best-known brothels, including one of the most notorious ones in the heart of the Jewish quarter at 27 Wolinska Street, where many terrible crimes took place.

Had Yiddish survived as a vernacular in Poland, one could imagine The King of Warsaw being written in it, but, alas, we are left with only a linguistic echo in Twardoch’s occasional use of the distinctive Warsaw Yiddish dialect. Nonetheless, Twardoch has reached deep into Poland’s blood-soaked earth and has seized its Jewish history with both hands. In doing so, he has created a stunning portrait (recently adapted for Polish television) of a multicultural Poland that no longer exists.

The world of pre–World War II Jewish Warsaw was made up of Bundists, Zionists of many stripes, Agudaniks, anarchists, assimilators and the unaffiliated, Hasidim, Litvaks, Jews from the provinces—the broad spectrum of Jewish humanity. Warsaw was Eastern Europe’s main Jewish cultural center and a magnet for many of them. Outside of New York, it was the largest Jewish city in the world in the 1930s. Among the many secondary tragedies of the Holocaust is that there is more focus on how its victims died than how they lived.

The Jewish cultural life created in Warsaw was the product of its varied Jewish communities. From synagogues and yeshivas to sports clubs and women’s organizations, to smoky jazz clubs and theaters and restaurants, it was a broad and rich human world. As it homes in on one of the city’s forgotten Jewish subcultures, The King of Warsaw also touches on many others. An intense, provocative read, it lifts the massive stone sitting on Warsaw’s history and reanimates what squirms beneath.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

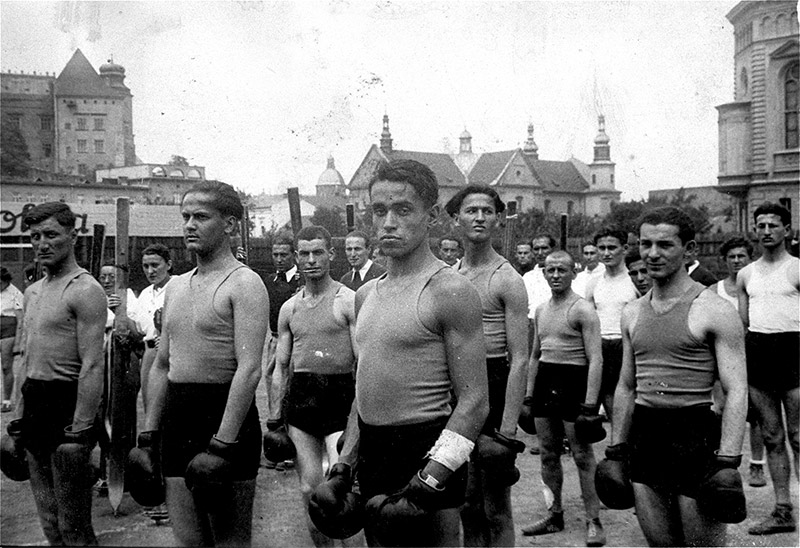

Jewish Pugs

A successful Jewish jock, demonstrating strength and physical courage, nicely rounds out Jews’ sense of completeness as human beings.

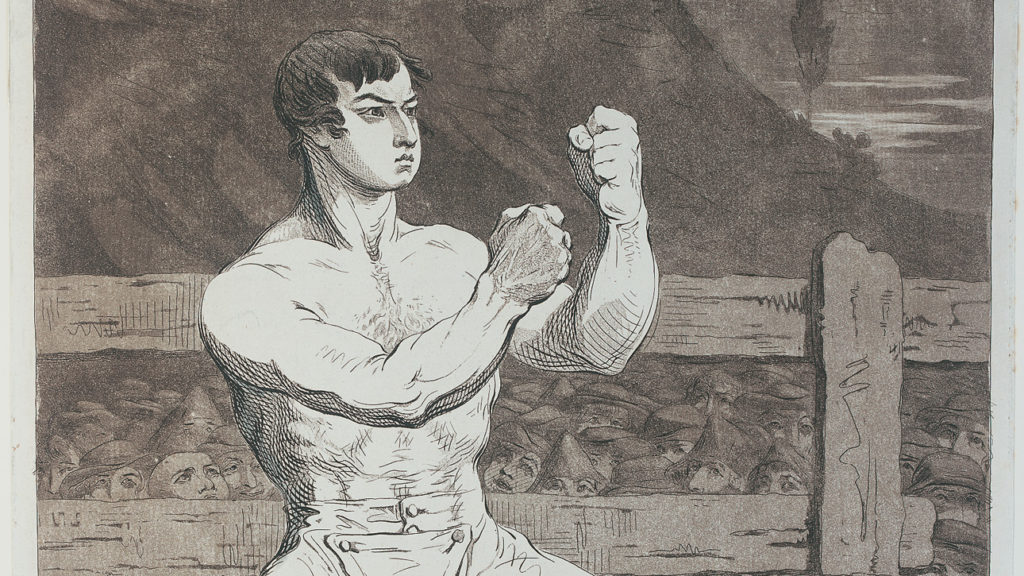

Muscular Judaism

The history of Jewish boxers such as Daniel Mendoza in England is as central to understanding the entry of Jews into European society as the better-known and much-researched history of Jewish salonnières and intellectuals in Berlin and Vienna.

Hasidic Renewal on the Brink of Destruction

Kalonymus Kalman Shapira, a Hasidic communal leader, and Hillel Zeitlin, a writer who sought to bring Yiddish religious books to a new audience, met on the page, and almost certainly in the Warsaw Ghetto.

POLIN: A Light Unto the Nations

How is it that the largest public building to go up in Poland since that country regained its freedom, the first museum to tell the story of Poland from beginning to end, goes by the name of POLIN?

Alan Kaufman

Great essay! Once again, as in his groundbreaking book 'Bad Rabbi: And other strange but true stories from the Yiddish press', Portnoy's review excavates aspects of pre-war Jewish life that lay deeply buried in the Holocaust, forgotten. Very often saccarine pieties bar the full richness and drama of Jewish life until the Portnoys appear to rescue History from its commemorating institutions.