In the Beginning, There Was Angst

In English, we use the single word “book” to denote a printed work bound between covers, but Yiddish offers two separate words, “bukh” and “seyfer.” A seyfer is a sacred book—a Torah, say, or a compendium of legal decisions or commentaries. A bukh, on the other hand, is just a book, the kind of work English speakers would call secular, or as the Yiddish has it, veltlikh: “worldly,” pertaining to and irredeemably bound up with the things of this world.

As in so many cases, here too, the Yiddish preserves an aspect of the deeply rooted sensibility of Eastern European Jews. A bukh might be packed with insights and its author highly respected, but such a work can never compel the same kind of reverence as a seyfer. An authoritative tradition stretching from Sinai can be built on and sustained by a seyfer; the attitudes and passing fancies of the day are recorded in a bukh. By identifying each with a distinct word—one Hebraic, the other Germanic—the Yiddish language seems to deny the possibility that the latter could ever serve the purposes of the former.

Adam Kirsch’s new book, The Blessing and the Curse: The Jewish People and Their Books in the Twentieth Century, is ostensibly about books in this second, secular sense. He tells us as much in the introduction. Here Kirsch writes that he has sought to introduce readers to “some of the most significant and compelling Jewish books of the twentieth century,” though he quickly qualifies this by observing that he has excluded “the writing that continued to be produced in traditional religious genres.” The works he takes up include novels, poems, plays, diaries, autobiographies, and essays in religious philosophy—but not, for instance, a single work of contemporary halakha or Torah commentary.

Kirsch’s admission might imply that, like the programmatic secularists of earlier generations, he is eager to exchange the sacred traditions of the Jews for individual flashes of genius, the idiosyncratic meanderings of Jewish minds unmoored from covenant. But the deeper I read in this highly readable book, the more I realized that there is something distinctly scriptural about the impulse underlying Kirsch’s project. When taken by themselves, the works under discussion look like individual productions, often prompted by some sort of personal crisis. But when laid out alongside each other in Kirsch’s narrative, these books suddenly appear as episodes in the collective story of a people set apart for a mysterious destiny.

Hence the aptness of the book’s title, which comes from a passage near the end of the book of Deuteronomy. With the Promised Land in view, Moses gives the Israelites the enigmatic prophecy that the road ahead will include both blessings and curses, but if the Israelites repent they shall be “gathered again from all the peoples among whom the Lord your God has scattered you.” What fascinates Kirsch is Moses’s understanding that the blessing seems inconceivable without the curse; Israel’s future will entail both as a function of its chosenness.

Kirsch’s carefully selected series of written works, 36 in all, characterize the Jewish 20th century as a dramatic fulfillment of this very prophecy. He offers a mini-essay about each of the pieces he has selected, and since each essay is almost the same size as every other (8–10 pages), the individual works come to seem like steps along a single journey, albeit one leading in multiple directions, including detours and ambivalent turns. Like the Torah itself, this is also a story of exile and homecoming—though here, the questions of where home is and how the Jews should comport themselves there have become considerably less certain. Where a committed secularist would raise up the literary in place of the sacred, Kirsch’s discussions read more like a coda to the sacred scriptures. And unlike other prominent canon builders, such as Irving Howe or Gershon Shaked or Ruth Wisse, Kirsch lowers the volume of his own critical voice, standing back and marveling at the mysterious fate imposed on the Jews in the last century.

Where, then, does this story begin? American Jews typically see themselves as heirs to the world of the shtetl, and Kirsch could have reaffirmed this self-image by beginning, say, with a Yiddish writer such as Isaac Leib Peretz, Sholem Aleichem, or S. An-sky. Instead, he opens with a German book written considerably to the west of Anatevka: Arthur Schnitzler’s The Road into the Open. By beginning with a work produced in cosmopolitan Vienna, Kirsch avoids the kind of narrative of cultural decline that we have become accustomed to. In the beginning, Kirsch tells us, there was not a tradition-bound Jewish world, filled with wonder rabbis and dybbuks. In the beginning, there was assimilation and angst.

Schnitzler was an exceedingly keen observer of Viennese Jews, so attuned to the twists and turns of the human psyche that Sigmund Freud once confessed in a letter to him that he had avoided meeting Schnitzler out of “fear of finding my own double.” The Road into the Open really describes a road to ambivalence, thwarted desire, and self-delusion. Faced with the rising tide of antisemitism, one of Schnitzler’s central characters, Heinrich, expresses hope that some radical change might still redeem him and his generation: “Everyone must manage to find an escape for himself out of his vexation or out of his despair or out of his loathing, to some place or other where he can breathe again in freedom.” But the options embraced by the novel’s main Jewish characters—Zionism, socialism, and assimilation—all turn out to be desperate attempts to avoid the truth that they were living, in Kirsch’s words, a “life without a future.” This phrase sums up Kirsch’s view of Schnitzler’s message and of the Jewish predicament in pre–World War I Europe in general. By beginning with this dark prognosis, Kirsch allows a note of historical determinism to creep into his narrative from the start. But it does seem fitting for the saga as it unfolds. Europe is a modern-day Egypt, as our most attuned writers were telling us all along.

The darkening mood is reinforced by the texts that come next, Franz Kafka’s The Trial, Isaac Babel’s Red Cavalry, and Isaac Bashevis Singer’s Satan in Goray. After these works, fiction falls away from Kirsch’s story, and he turns to primary documents by Jews caught up in the eye of the Holocaust storm: Victor Klemperer’s diary, the diary of Anne Frank, Elie Wiesel’s Night, and Primo Levi’s Survival in Auschwitz. Klemperer is a welcome addition to these more familiar works. His two-volume diary was not published in English until 1998, and Kirsch makes a strong case for its unparalleled insight into Jewish life in Germany during the rise and fall of the Third Reich. A professor of French literature at Dresden University of Technology, Klemperer endured the mounting humiliations suffered by all Jews after the Nuremberg Laws, even though he had chosen to be baptized as a Protestant in 1912. As he was dispossessed of everything he valued, Klemperer clung desperately to his faith that the Nazis were not the true face of Germany. “I am fighting the hardest battle for my Germanness now,” he wrote in May 1942. “I must hold on to this: I am German, the others are un-German.” Soon, this faith became yet another wartime casualty: “I can no longer believe in the completely un-German character of National Socialism,” he later confided in his diary. “It is homegrown, a malignant growth out of German flesh.” Ultimately, Klemperer survived the entire war, thanks to what Kirsch describes as sheer bureaucratic randomness. His service in World War I and his Gentile wife gave temporary protection—but hardly insulated him from impoverishment, constant harassment, and the threat of imminent deportation. Reflecting on Klemperer’s uncanny survival of the paradigmatic curse in modern Jewish life and his subsequent resumption of his academic career in East Germany, Kirsch supplies the language of transcendence that remained inaccessible to Klemperer himself: “For a man who didn’t believe in miracles,” Kirsch writes, “it was a miraculous ending—and for that very reason, an unrepresentative one.”

After situating the Holocaust as a turning point in human history, Kirsch moves to a section on America called “At Home in Exile” and a section on Israel called “Life in a Dream.” Refreshingly, neither path is endorsed as the obviously correct one. In fact, the narrative arc that Kirsch pursues in each section makes the two centers of post–World War II Jewish life look remarkably similar, in the sense that each raised momentous hopes that have remained, at least in Kirsch’s estimation, tantalizingly out of reach.

The section on America portrays the drama of acculturation as a perilous balancing act between Jewish loyalties and American allurements. For every exuberant embrace of America as a new home for Jews (Kirsch points to Saul Bellow’s The Adventures of Augie March and many of Grace Paley’s stories), there are darker portents that an unbridgeable gulf ultimately divides Americanness and Jewishness. Nowhere is this clearer than in Cynthia Ozick’s story “The Pagan Rabbi,” which ends with a suicide, proving Ozick’s point, according to Kirsch, that “a rabbi can never become a true pagan. . . . To cherish the world, the body, and the senses is to sin against Judaism.”

American Jews, in this view, are doomed to wander between irreconcilable choices. Most of the American Jews depicted in the texts Kirsch selects are divided selves. But Israel hardly offers the relief from existential affliction that Zionist idealists have been insisting it would. From S. Y. Agnon’s Only Yesterday to Orly Castel-Bloom’s Dolly City, Kirsch exposes recurrent themes of madness, alienation, and spiritual confusion. Castel-Bloom’s surrealistic novel reimagines Tel Aviv as “Dolly City,” named for the novel’s mad narrator. It is “a city without a base, without a past, without an infrastructure. . . . All the streets in Dolly City are one-way streets, but everybody drives in all directions anyway.”

In other Israeli novels, the problem is less the absence of a past than its overwhelming weight. In A. B. Yehoshua’s Mr. Mani, a modern Israeli family is bound to repeat the cycles of dysfunction stretching back more than a century. “He couldn’t control this impulse he had to do away with himself every evening,” Yehoshua writes about the first of several Mr. Manis to appear in his multigenerational novel. “That thought wasn’t his own but came from someone or somewhere else.” Despite the Zionist dream that galut Jews could be remade into a truly emancipated people, the past clings irredeemably in this and other works Kirsch discusses. And yet another suicide—this time a real one—haunts the quintessential kibbutznik-turned-writer Amos Oz, whose mother committed suicide and whose novel Where the Jackals Howl warns of imminent psychological chaos, threatening to disrupt the Zionist enterprise. The new Jew is still shaped by the old Jew, it turns out, just as children are by their parents and Israel is by the nightmare of Europe.

Where in all of this, we might ask, are the blessings promised by the title? Tellingly, both the America and Israel sections conclude with writers who use the language of religion, ritual, and prayer to create ultimately affirmative visions. These writers are the American-born playwright Tony Kushner and the German-born poet Yehuda Amichai. Kirsch shows how both use experimental literary forms to preserve the powerful yearnings articulated by traditional Judaism, yearnings for transcendence, for justice, for peace and quiet in a home they can call their own. “Yearning,” indeed, is one of Kirsch’s operative terms, his substitute, so it seems, for the more traditional concept of faith. It is instructive that Kirsch moves on from the nonfictional, documentary works of the European section, concluding the American and Israel sections, respectively, with a fantastical play and a selection of fanciful poems that reconfigure the terms of Jewish prayer. In one of the most powerful scenes in Angels in America, Tony Kushner has Ethel Rosenberg’s ghost recite the Kaddish as her fellow Jew and political archrival Roy Cohn dies of AIDS. Kirsch calls this scene “an affirmation of the power of religion and ritual to make death tolerable, to incorporate it into a resilient and tragic view of life.” As for Amichai, he reimagines the numbers tattooed on concentration camp survivors as “The telephone numbers of God, / Numbers that do not answer.” Kirsch explains that Amichai is doing something more audacious than simply denying the existence of God: “He asks the reader to pity God, describing him as a father who has lost his children. . . . In this way, Amichai reveals himself as a profound post-Holocaust theologian.”

Here Kirsch affirms the role of literature as an engine of fantasies and dreams that survive the depredations of history. Indeed, it is the confounding history of 20th-century Jews that has lent their literature its correspondingly sublime force. As Kirsch writes about Amichai, “There is something exhilarating about living so directly at the center of history, in a country defined by the greatest ambitions and the most dire tragedies. . . . He is plugged into a powerful current, and he is strong enough to let it flow through him.” Kirsch’s electrical metaphor is a provocative way of conceptualizing the Jewish literary imagination in general. It characterizes the Jewish writer’s relationship to history as a risky relation, involving both danger and the potential for a surge in power.

Indeed, survival through re-creation is the animating theme in Kirsch’s final section, “Making Judaism Modern.” Turning to some of the key texts in modern Jewish religious thought, from Martin Buber’s Three Addresses on Judaism to Mordecai Kaplan’s Judaism as a Civilization to Judith Plaskow’s Standing Again at Sinai, Kirsch makes explicit the spiritual aspirations of his own book. Modernity may have eroded the basis for traditional Judaism, but the spiritual strivings that formerly propelled Jews have not lost their momentum. As he writes of Plaskow’s feminist theology, “It is because she belongs to Judaism and it belongs to her that it is possible, and necessary, for her to give it a new form and content.” Kirsch finds surprising common ground between Plaskow and the post-Holocaust theologian Emil Fackenheim: both seek to create a postrabbinic Judaism on the ruins of a world that can no longer be explained by traditional theologies.

It is just as inevitable as it is a little churlish for readers of an ambitious survey like this one to point out names and works that are missing. Because Kirsch himself admits to his near-exclusive focus on Ashkenazi writers at the expense of Sephardi and Mizrahi writers, I will not dwell on their absence. Still, I will permit myself one other complaint. Missing from the Holocaust section of the book are any works by the numerous Yiddish writers, diarists, and poets who eloquently and voluminously responded to the destruction of their world.

Yiddish voices would have contributed an important perspective to Kirsch’s account of the Holocaust, not only because the vast majority of those murdered by the Nazis were Yiddish speakers but because the distinctive cultural strategies enacted by Jews in the Nazi ghettos, where so many spent up to four years, were vividly recorded in Yiddish—and almost nowhere else. It was only a select few who survived more than a single day in Auschwitz, but countless Jews spent years locked up in a ghetto. Why not dwell for a moment among these men and women who continued to write and dream and love when all else had been taken from them? Kirsch defends the Western European bias of the received canon of Holocaust literature on the grounds that these works “speak to modern, secular readers the world over.” This underestimates the power of Yiddish writers such as Emanuel Ringelblum, Avraham Sutzkever, and Chava Rosenfarb (not to mention Itzhak Katzenelson, Rokhl Auerbakh, Leib Rochman, Rachel Korn, and Rachmil Bryks), who wrote movingly, accessibly, and in many registers about the unique trials of ghetto life. But even without these voices and others whose absence readers may note, the choral effect of Kirsch’s book remains powerful and illuminating. Although he cannot quite convince himself that a secular book can be turned into a seyfer, he offers a compelling case that the Jewish 20th century was so poignantly described by its witnesses that it can now take its place as a chapter in the unfolding saga of the people who heard Moses’s strange prophecy on the banks of the Jordan. As he looks toward the uncertain Jewish future, Kirsch is content to follow the words of earthbound men and women, launched at moments of doubt as well as ecstasy, aiming at the heavens.

Suggested Reading

The Jewbird

It is in his stories, rather than his novels, that Malamud emerged as a unique writer. A new series brings new exposure to both.

Inside or Outside?

After the discoveries of the Cairo Geniza and the Dead Sea Scrolls, scholars of Judaism slowly began to reconstruct the 400-year period separating the latest parts of the Hebrew Bible from the earliest rabbinic compilations.

Misreading Kafka

The Kafka myths, and the "myth-busters" who make them.

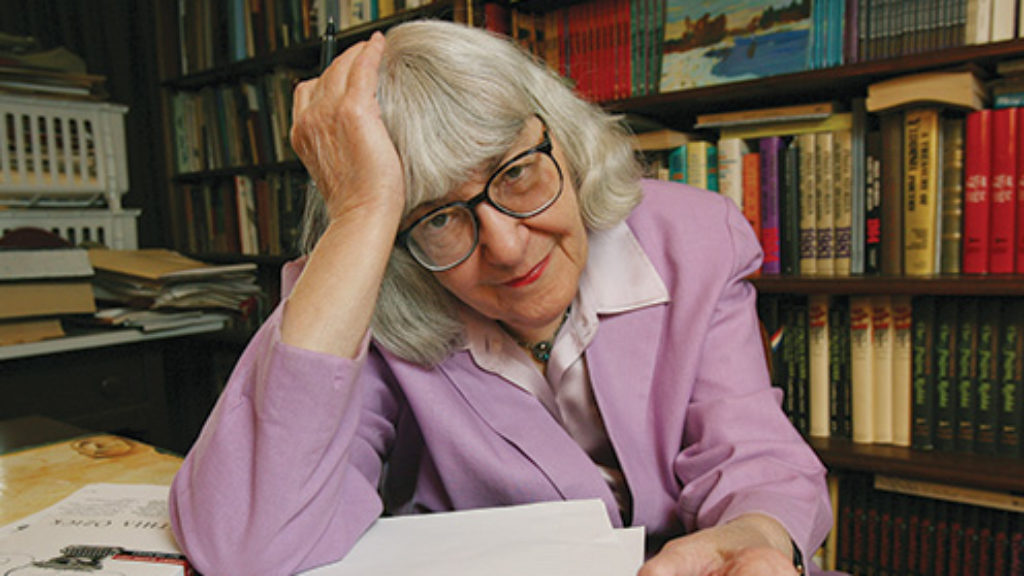

Cynthia Ozick: Or, Immortality

Ozick is as marvelously demanding, harrumphing, and uncompromising as she has always been.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In