The Most Important Word in the World

I had my Steinbeck kick back in high school, but I never got around to East of Eden. Maybe it was because I’d already seen the 1981 television miniseries as a kid, or maybe I was scared off by its 602 pages. Anyway, I read it this summer while on vacation from teaching Tanakh and Talmud, or so I thought.

Steinbeck patterns the rivalrous lives of his main male characters, brothers Charles and Adam Trask and Adam’s sons, Cal and Aron, on the tragic biblical siblings with whom they pointedly share initials. (East of Eden, of course, lies the land of Nod, to which Cain was banished after he murdered Abel.)

Steinbeck’s literary strength was never his subtlety, and in the middle of the novel, he stages an explicit theological discussion of the Cain and Abel story. Adam, his neighbor Samuel Hamilton, and his Chinese servant Lee are pondering God’s warning to Cain: “If thou doest well, shalt thou not be accepted? and if thou doest not well, sin lieth at the door. And unto thee shall be his desire, and thou shalt rule over him.” (Gen. 4:7)

Lee, who functions as the novel’s conscience, tells Adam and Samuel that he brought this biblical story to his Chinese elders, who in turn consulted rabbinic authorities and studied the meaning of the Cain and Abel story for two years. “My old gentlemen felt that these words were very important too—‘Thou shalt’ and ‘Do thou.’ And this was the gold from our mining: ‘Thou mayest.’ ‘Thou mayest rule over sin.’”

“Don’t you see?” he cries:

The American Standard translation orders men to triumph over sin, and you can call sin ignorance. The King James translation makes a promise in “Thou shalt,” meaning that men will surely triumph over sin. But the Hebrew word, the word timshel—“Thou mayest”—that gives a choice. It might be the most important word in the world. That says the way is open. That throws it right back on a man. For if “Thou mayest”—it is also true that “Thou mayest not.” Don’t you see?

Steinbeck, as voiced by Lee, is quite pleased with this exegetical reading. And he is not wrong to ascribe a robust notion of free will to the rabbinic tradition.

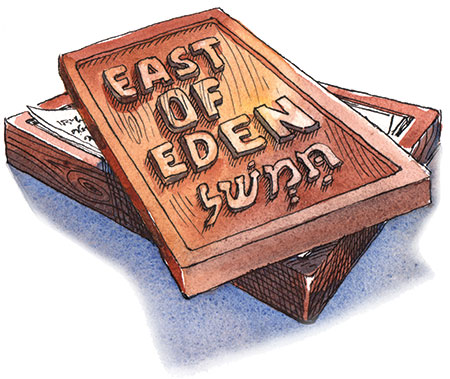

“Timshel” or “thou mayest” becomes the mantra, the moral core of East of Eden. It is, in fact, the final, redemptive word of the novel. When he finished drafting it, Steinbeck carved the Hebrew characters into the lid of a wooden box he made for his editor to hold the manuscript. Over the past seventy years, “timshel” has inspired songs, nonprofits, boat names, and innumerable tattoos both in English and Hebrew among fans of Steinbeck, free choice, and the ever-present possibility of redemption.

Yet, as others have noticed before me, it makes little sense. The word in the Torah is “timshol,” not “timshel,” and it doesn’t mean simply “thou mayest”; it means something like “thou mayest rule over.” Steinbeck’s translation accounts only for the tav at the beginning of the word, a prefix that indicates you, singular masculine, future tense—you will. The remaining letters of the verb, mem, shin, lamed, form the Hebrew root that means to rule, control, or govern. How did Steinbeck get both the pronunciation and the meaning of the key word in, arguably, his most ambitious novel wrong?

John Steinbeck began almost every working day of 1951 with a letter to his editor at Viking Press, Pascal Covici, before turning to East of Eden. At one point Steinbeck recruited Covici, himself a Romanian Jew (Pascal Avram), to find a rabbinic authority to consult with on the original Hebrew of the key phrase in Genesis 4:7. As the fictional Lee’s Chinese elders turned to the rabbis, Covici turned to Professor Louis Ginzberg of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, one of the preeminent rabbinic scholars of his generation. Ginzberg’s most well-known work, The Legends of the Jews, is a retelling of the entire Hebrew Bible in the light of classic, sometimes fanciful, rabbinic interpretations. It is a work of massive, almost unfathomable erudition and remains an invaluable resource today (I use it frequently).

Alas, the Steinbeck-Covici letters do not reveal exactly what Ginzberg told Covici and what Covici relayed to Steinbeck in this game of exegetical telephone. However, it seems that great minds did not think alike. For some reason, Steinbeck was not entirely pleased with Ginzberg’s interpretation of the key word. He wrote Covici:

Don’t forget that in the Jewish translation you sent, they did not think “timshel” was a pure future tense. They translated it “thou mayest.” This means that at least there is a difference of opinion and that is enough for me. I will have to have the whole verb before I will finish, from infinitive on through past, subjunctives and compounds and futures. But we will get it. We may have to go outside of rabbinical thought to pure scholarship which may be non-Jewish. . . . Dr. Ginzberg, dealing in theology, may have a slightly different attitude from that of a pure etymologist.

This is confused and confusing. Steinbeck clearly didn’t understand how verbs worked in Hebrew and may have simply given up. However, one thing that is clear is that Steinbeck arrived at his spelling and pronunciation of the Hebrew nonword “timshel” as a result of Covici’s consultation with Ginzberg, one of the greatest scholars of Hebrew texts of his generation. How was this possible? Here, I have a hypothesis.

Ginzberg was born in Kovno, Lithuania, in 1873 and immigrated to the United States in 1899. Having received a traditional yeshiva education in his youth, Ginzberg would almost certainly have pronounced Hebrew with a Lithuanian, or Litvish, accent, which differs significantly from that of other Ashkenazi Jews. For instance, the word “Torah” might be pronounced “Toyrah” by Polish Jews but “Teyrah” by Litvaks. The “oh” sound morphs into an “ey.” Thus, “timshol” in Ginzberg’s Litvish accent might have sounded like “timsheyl,” which is almost Steinbeck’s “timshel.”

For a moment in 1951, a literary giant and a talmudic genius indirectly sparred over the implications of a single biblical phrase, inadvertently bringing us the iconic nonword “timshel.” And who am I to step into the fray seventy years later and presume to solve the “timshel” mystery? Well, that’s the beauty of interpretation. Thou mayest.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The First Lady of Zionism

At the age when most of us are just about to fold our tents, Henrietta Szold, pitched hers—and in the Holy Land, no less.

A Pinch of Levity

Is it true that three people are required to perfect a joke: one to tell it, one to get it, and a third not to get it? Stuart Schoffman tracks a single Jewish joke through multiple tellings.

In Pursuit of Wholeness: The Book of Ruth in Modern Literature

While not the most dramatic of all the biblical stories, the quietly moving book of Ruth, which we read on Shavuot, continues to resonate in Western literature.

Screwball Tragedy

Picture a Jewish town, located deep in a Polish forest, that hasn’t received so much as a postcard from the outside world in more than a century. Max Gross conjured it up The Lost Shtetl: A Novel, and the result is both screwball and serious.

Reuven Spero

And more likely than not, Prof. Ginzberg would have placed the accent on the first syllable, as did many Ashkenazic Jews. That would certainly give one a good "timshel."

As for your other point, when Lee exclaims "Thou mayest" he is simply giving shorthand for the entire phrase "Thou mayest rule over sin;" and you mayest not as well. The beauty implied in the Hebrew is granting agency to human decision-making. Interesting, though, is that two of the A/C characters - Adam and Cathy - are so defined by their outlooks on life that much of their life decisions are virtually without agency, predetermined, and therefore predictable. There is something almost frustratingly boring about Adam, and Cathy is not much more than a caricature. Cathy overcomes that - maybe - when she wills half of her inheritance to Adam. Adam overcomes that in the last lines of the book when he blessed his less-loved son, Cal (the "C" - Cain - son) burdened with sin, with that last word, "timshel."

I see the denouement of the book in last scene where Lee is examining a delicate but strong porcelain teacup. The creator is striving for perfection in his creation, but imperfections are always there - and the teacup is consigned to the slag heap, for the creator (Creator - a "C" word"?) to take this weak material and try again, and again, and again and perhaps one day fashion that perfect teacup. And maybe not, but every attempt brings us a little closer, perhaps.

This reminds of the the scene with the button molder in Ibsen's Peer Gynt. There, it is the merciful love of a woman, of Helvig, that redeems Peer Gynt from oblivion. Here, and for this I truly love Steinbeck, it is the incessant human struggle for self-perfection that redeems us. For love, in Ibsen's play, is a transcendent but static redemptive stage, but in East of Eden, it is only struggle, putting one's self through the fire of the crucible, that could produce a finer human (see Is. 1).