The Jewish Preview of Books—November 2018

Dozens of books on Jewish history, culture, and literature are published each month. Here are some debuting this November.

The vile and tragic murder of Jews at prayer in a Pittsburgh synagogue has compelled us at the Jewish Review of Books, like so many others, to again ponder the rising tide of anti-Semitism in the U.S. and around the world. One place we might turn for new insight is Paul Hanebrink’s soon-to-be-released A Specter Haunting Europe (Belknap), which promises a full-scale investigation of the myth of Judeo-Bolshevism, the canard that Jews push communism as part of an elaborate plot to destroy Western civilization. Hanebrink revisits the myth as it circulated between the world wars and asks why it has resurfaced among Far-Right white supremacist groups today.

Two years ago, the world lost Elie Wiesel, one of Judaism’s most eloquent speakers against anti-Semitism and hatred. Elie Wiesel’s student Ariel Burger, who studied with him for decades and also served as his teaching assistant, has just written a memoir of their relationship: Witness: Lessons from Elie Wiesel’s Classroom (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt). Another teaching memoir (Ilana Blumberg’s), Open Your Hand: Teaching as a Jew, Teaching as an American (Rutgers), makes the argument that the ends of education should be moral. There is also a broader history of Jewish education coming out this month, David Aberbach’s Nationalism, War and Jewish Education: From the Roman Empire to Modern Times (Routledge).

Three years ago, Zachary Leader published the first half of a prodigious biography of author and Nobel laureate Saul Bellow. In 800 pages, Leader chronicled Bellow’s meteoric rise, leaving plenty of ground for the second half, The Life of Saul Bellow: Love and Strife, 1965–2005 (Knopf), of roughly equal length, which is due out next week. As we noted in our review of the first half, this second volume “will carry Bellow through (to stop just at the highlights) a Broadway flop, a bitter divorce and decade-long alimony battle, Mr. Sammler’s Planet, co-editorship of several small literary magazines, journalism from Tel Aviv and Sinai in the midst of the Six-Day War, Humboldt’s Gift, the Nobel Prize, marriage to a glamorous Rumanian mathematician, then another bitter divorce, and his brilliant late-life renaissance culminating in Ravelstein, his novel about—an imprecise but unavoidable preposition with Bellow—his friend and University of Chicago colleague Allan Bloom. And, of course, his final, and finally happy, marriage to Bloom’s student Janis Freedman Bellow.” We’ll publish a fuller review, including a romp through previous Bellow biographies, next week.

The 20th century may have been a particularly fruitful time for American Jewish literature, but the path was cleared by important developments in the 19th. Sharon B. Oster’s No Place in Time: The Hebraic Myth in Late-Nineteenth-Century American Literature (Wayne State University Press) describes how Jews, who were once considered a relic of an ancient, pre-Christian past, came to conceive themselves, and be conceived, as part of a modern America. A high point came with Emma Lazarus, a tireless advocate for refugees—both Jewish and non-Jewish. We also look forward to the publication of Sunny Yudkoff’s Tubercular Capital: Illness and the Conditions of Modern Jewish Writing (Stanford), which promises to trace the role this common and incurable disease, and the “culture of convalescence” surrounding it, played in the literature of Sholem Aleichem and other Jewish authors.

Two popular works from scholars have piqued our interest this month: Malka Simkovich’s Discovering Second Temple Literature (JPS) promises an intelligent introduction to the fascinating world of Jewish literature that was written between the Bible and the Talmud, including strange retellings of familiar biblical stories and wild apocalyptic tales that never made it into the Jewish canon. And Jeffrey Rubenstein has written another book, The Land of Truth: Talmud Tales, Timeless Teachings (JPS), which promises more of what he does best—offering insightful literary readings of abstruse talmudic tales.

Much more is coming out in a more strictly academic vein, including celebrated Kabbalah scholar Moshe Idel’s The Privileged Divine Feminine in Kabbalah (De Gruyter); Lior B. Sternfeld’s history of Jews in Iran during the last century, Between Iran and Zion (Stanford); Yuval Jobani’s The Role of Contradictions in Spinoza’s Philosophy: The God-Intoxicated Heretic (Routledge); and an exploration of a 17th-century Dutch Spinoza rebutter, Isaac Orobio: The Jewish Argument with Dogma and Doubt (De Gruyter). And if you haven’t had enough of Gershom Scholem yet, Mirjam and Noam Zadoff are bringing out an edited collection of articles, Scholar and Kabbalist: The Life and Work of Gershom Scholem (Brill).

Looking to books on Israel, we anticipate dipping into a new English translation of three Amos Oz essays in Dear Zealots: Letters from a Divided Land (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) by veteran translator Jessica Cohen, winner of the Man Booker International Prize for her translation of David Grossman’s A Horse Walks into a Bar. We also look forward to Zalman Shoval’s memoir, Jerusalem and Washington: A Life in Politics and Diplomacy (Rowman & Littlefield). Shoval immigrated to Mandatory Palestine before the Second World War, and he served in the Knesset for a long time before being appointed Israeli ambassador to the United States in the 1990s.

In fiction, look for a new English translation of Dror Burstein’s Muck (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux), a retelling of the story of the prophet Jeremiah set in the modern period; Michael Weingrad reviewed the Hebrew original for us—he translated the title as Mud. Also available now in English translation is Samir Naqqash’s Tenants and Cobwebs (Syracuse), inspired by his experience as a Jewish child growing up in Baghdad. Finally, look for Thelma Adams’s Bittersweet Brooklyn (Lake Union Publishing), a multigenerational historical fiction novel about Jewish mobsters told through the eyes of the women they love.

Suggested Reading

On That Distant Day

Benjamin Netanyahu is back in the Prime Minister’s chair, but where are the factions who put him there taking Israel?

Hidden Master

The closer we look at Green's theology, the more radical it turns out to be.

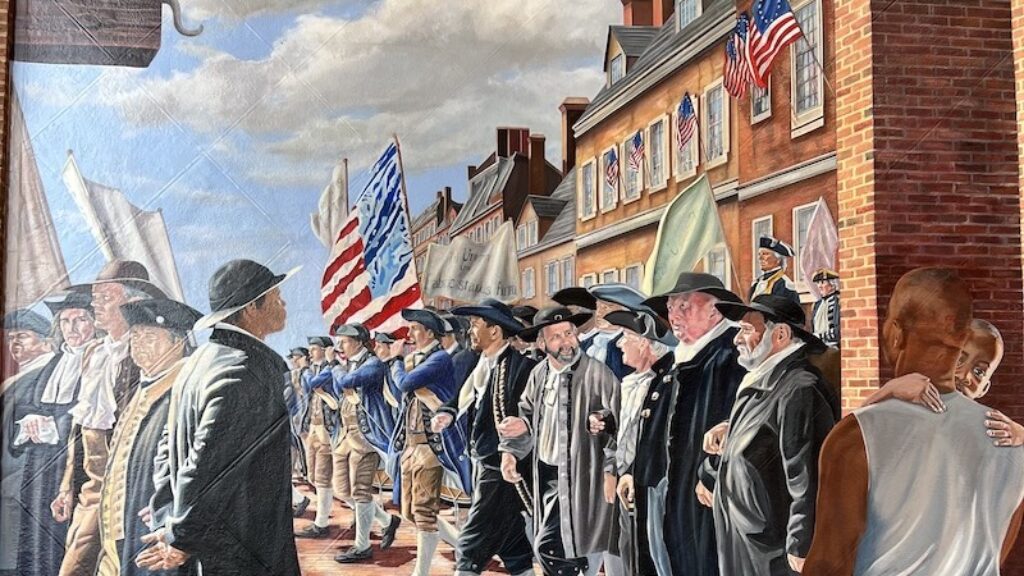

When Freedom Began to Ring

How the land of opportunity became the opportune land for Jews to thrive.

Love and War

David Grossman has for sometime been one of Israel's most talented and important writers. In many of his novels, his feeling for adolescence—one is tempted to say, his identification with it—has been so brilliantly intuitive that the imagining of adulthood has scarcely been possible. In To the End of the Land, Grossman makes his breakthrough.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In