A Movement Strikes Back

From The Jewish Week to Ha’aretz, from many pulpits and all over the blogosphere, people have been talking about Daniel Gordis’ “requiem” for Conservative Judaism. We continue this lively, instructive conversation with seven responses from some of the movement’s most thoughtful teachers and rabbis, along with a response from Jonathan D. Sarna, one of the leading historians of American Jewry.

- Noah Benjamin Bickart of The Jewish Theological Seminary teaches Jews who are passionate about “an egalitarian, halakhic, yet non-fundamentalist Judaism,“ even though they may not call themselves Conservative Jews.

- Elliot N. Dorff argues that numbers don’t dictate the strength of a movement; the power of its ideas does.

- Susan Grossman acknowledges the movement’s failings, but sees more reason for hope than despair.

- For Judith Hauptman, the Conservative push for women’s rights holds the key to its future—and the future of Judaism as a whole.

- Moving to Israel has clouded Gordis’ ability to understand the American Jewish scene, argues Jeremy Kalmanofsky.

- Whether it’s 18 percent or eight families, Gordon Tucker maintains “patience and tenaciousness change the world,” a fact that is lost when we focus on numbers.

- David B. Starr says that Gordis asked the right question, but the answer may be harder than he thinks.

- Plus Jonathan D. Sarna looks back at a time when both Reform and Orthodox Judaism in America seemed imperiled.

Daniel Gordis replies to his critics and outlines his positive vision for the future. His proposal may surprise you.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

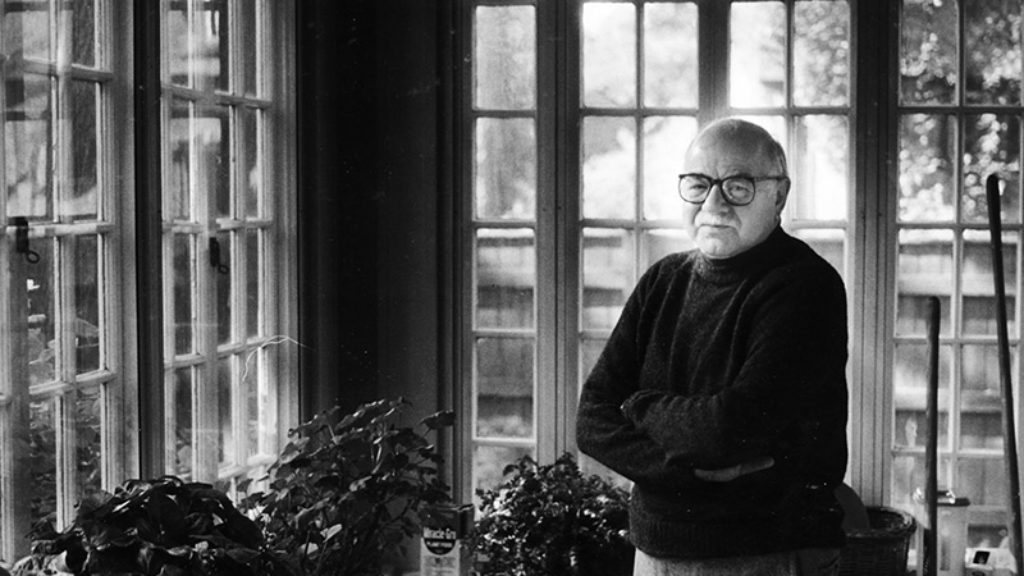

Daniel Bell (1919-2011)

In memoriam.

Rachel and Her Children

blurb.

The Improbables

Not writing what you know can help an author steer away from autobiographical shoals, but it puts a certain research burden on the writer.

Conversion, “Catholic Israel,” and the Jewish Future: An Exchange

Tal Keinan argued for a radical transformation of Jewish life in God Is in the Crowd. Our editor wasn't convinced, which led to a pointed but cordial discussion.

dougaltabef

At the risk of being politically incorrect, I would make a couple of Emperor's clothes anecdotal observations: 1. Conservative Judaism has become dry as dust. God and spirituality have been set aside as being too...what? Fundamental, de-classe, or medieval. 2. Egalitarianism is a disaster. When men have had the chance to abdicate from key roles...they have. Being subject to time bound obligations is another way of saying having unique responsibilities. Tradition kept men involved because they were asked to play a unique role. Why? Probably becasue, just as we are seeing, in the absence of having had to play them, men sneak out the back door.

Religion is a delicate and finely tuned organism. Having a place, having a connection, being called on to serve a higher purpose...all of these things bring our the best in us. Dumbing it down, rolling our eyes at the prayers we say or the texts we read is an obvious invitation to evisceration. We can tie ourselves up in intellectual constructs that explain everything except for the plain reality in front of our faces.

And finally, and speaking as an oleh, yes its hard to be an American and a Jew. There is a siren song to Americanization, which few, including the Modern Orthodox can resist. On the other hand, in Israel the deck is stacked in a Jew's favor. More than denominational or doctrinal differences, that distinction of place will be the ultimate arbiter of destiny to Jewish continuity.

vincent.calabrese

Egalitarianism of the lowest common denominator, in which anyone can do anything but no one *has* to do anything, is indeed disastrous. This has been standard in most Conservative shuls, where the sense of obligation on the parts of the congregants has all but disappeared. But egalitarianism is not a disaster in communities in which people actually view themselves as being obligated vis-a-vis Jewish practice--the small but growing frumm egal community represented by places like Mechon Hadar.

I have no sympathy for the men who sneak out the back door because their commitment to Torah and Mizvot is so weak that it amounts to cultural inertia. People who would only be reading Torah or leading davening because there would be no one to do it if they did not, are not the kind of people I want leading davening in my congregation.

hanabluma

People who have devoted their lives to an undertaking often don't want to hear bad news about it. And often can't see problems and the need for serious change. Gordis probably can precisely because he has some distance.

rich

Took a while to read all of them but there appears to be a common theme that links not only the multiple comments but the original piece by Rabbi Gordis. When people self-identify by denomination, they are really stating their loyalty to the structure and not to the ideology. For example, my congregation has no affiliation but its practice is pretty recognizable as a descendant of the Conservative shuls of the 1960's and the people who make it function are products of their Hebrew Schools and camps and university Hillels. So while traditional Conservative organizations have brought to the Jewish mosaic remains very much in place, just as the people regard themselves as fully a subset of American. If gender equality is the norm in the culture, it is becoming the norm on the pulpit. If people have been driving on shabbos since they got their first Model T, they are driving now. If a top-down culture has become dysfunctional in many workplaces and therefore disappeared, its preservation among Conservative institutions acquires similar skepticism.

So it does not seem to be recognizable Conservative ideology or religious thought or practices that are in jeopardy but the organizations that created them and nurtured the talent that allowed the people to think through how they would accept or reject or modify the various parts of their tradition and transport those elements to a venue that they find more suitable.

A few of the writers picked up on this theme and asked the critical question implicit in the few study. It is less how people identify but more what are the consequences if the institutional structure fails to adapt to current reality or more simply if they fail. Maybe new institutions will take their place, maybe not. Orthodoxy has done very well with a very loose organizational structure, just enough to prevent anarchy. But decentralizing something that depends on hierarchy, which is what the Conservative institutions are likely to have to do, may be quite a project, particularly amid a leadership that has once succeeded by promoting its brand.

SDK

Conservative institutions are by and large focused on two demographics -- upper middle class intramarried families with children who are willing to spend >3K per year for someone to educate them and empty-nesters whose children live in other cities but who are keeping the seats warm until the shul closes its doors.

If you belong to any other demographic -- if you are not upper-middle class, if you are intermarried, if you are younger, your kids are older or if you never had kids --there is nothing for you. Even the members will wonder why you are there.

That doesn't mean that people are not living committed, meaningful, Jewish lives. They are just not doing it in the same location as their parents, that's all.

Dutch

The defining characteristic of Conservative Judaism from a halakhic perspective, of course, is egalitarianism. Kashruth and Shabbat doctrine (other than driving to shul on Shabbat) are not substantially different from Orthodox doctrines. But good luck finding a community of observant Jews in your average Conservative synagogue.

Jews who are shomer Kashrut and shomer Shabbat must also hold the egalitarian aspects to be inalienable and central to their practice to affirmatively identify as Conservative. Even then, they must struggle to find in their own synagogues coreligionists who are similarly observant . Those who see egalitarianism as at all optional will invariably find a more robust community of similarly observant friends in a modern Orthodox community.

The rabbinate, of course, can wax poetic about the strength and scholarship of Conservative Jewish exegesis, but with a membership that largely cannot distinguish between Kiddush and Kaddish, that scholarship falls on deaf ears.