Cynthia Ozick’s Art and Ardor

What is history? How much can we know, and how much do we invent? What is valuable? Objects? Ideas? Institutions? Intimate experience? How do we determine what is precious and what is junk, what is real and what is invented? Can we control the past? Can we hold onto it? These are central questions in Cynthia Ozick’s exquisite new novel Antiquities, a book as richly layered as an archeological site.

The book begins simply, “My name is Lloyd Wilkinson Petrie, and I write on the 30th of April, 1949.” Petrie, an elderly gentleman, looks back on his life as a student and then trustee of the famed but now defunct Temple Academy for Boys. His recollections are modest and episodic—but like Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead and Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day, his memoir becomes the occasion for a quiet reckoning.

Petrie’s project is retrospective in every way. A record of times and places now forgotten, a tale of family now dead—including a famous relative, an archeologist, and his discoveries in Egypt. The memoir is a personal reminiscence and an exercise in old forms, the ethical will, the diary, the elegy. Petrie’s mode of writing is antique, as he pecks on his beloved Remington typewriter and later resorts to his Montblanc fountain pen. And, of course, his narrative is itself a relic, composed in the last century, just after World War II. Ozick’s project is retrospective as well—a backward glance at the themes and obsessions she has explored in her long, storied career. A sparkling essayist, Ozick titles several of her collections with alliterative pairings: Art & Ardor, Metaphor & Memory, Fame & Folly, Quarrel & Quandary. In her fiction, she explores dualities as well: the ancient and the recent past, the sacred and the secular, the classical and Hebraic traditions, the living and the remembered moment.

A Jewish and an American writer, Ozick is interested in the universal and the particular—but in the particular most of all. Like her contemporary Chaim Potok, Ozick writes about Jewish tradition, but while Potok built bridges, opening the world of religious Judaism to outsiders—secular Jews among them—Ozick has always been interested in the gap. A popular writer and a popularizer, Potok was an ambassador. A writer’s writer, Ozick is a sybil. She prefers incantations to explanations and takes a keen interest in Jewish mysticism, tribalism, and exceptionalism—positing that not all experience is translatable.

In her great story “Levitation,” an earnest convert, Lucy, hosts a dinner party with her husband, Feingold. At the end of the evening, only a few humanists and atheists remain in the dining room, while in the living room, Feingold and his Jewish guests talk about the Holocaust and its atrocities: “Germans in helmets, with shining tar-black belts, wearing gloves. A ragged bundle of Jews at the lip of the ravine.” This agony becomes a spiritual experience for those who speak and those who listen, elevating and estranging Jews from the ordinary world. As they speak of terrors, they begin to float up to the ceiling of the apartment, and Lucy can only watch. “Their words are specks. All the Jews are in the air.” Ozick’s art is not gentle or instructive. Her vision here is unapologetic, as she demonstrates that the Jewish experience does not belong to everyone. There are places, Ozick suggests, where outsiders cannot follow.

If a certain ferocity sets Ozick apart from Potok, her interest in religion and mysticism distinguishes her from literary peers such as Philip Roth and Saul Bellow. Her vision of Judaism is not only cultural and historical but spiritual. She never belittles believers. While her Jewish characters are often tragic, crazed, and conflicted, she writes seriously about their rituals. In Ozick’s work, the Old World does not seem so old. Unlike Bellow and Roth, she seems at home in the milieu of Yiddish master Isaac Bashevis Singer. She shares Singer’s interest in both high and low Jewish culture, his joy in the supernatural and the grotesque. The Yiddish world is rich and substantive for her, as is the predicament of Yiddish poets and novelists—Singer among them. Their rivalry and infighting inform Ozick’s tragicomic story “Envy, or Yiddish in America.” However, Ozick’s literary gods are American and English: George Eliot, Henry James, and Mary Shelley, to name just a few. In The Puttermesser Papers, Ozick’s golem—“I am made of earth, but I am also made out of your mind”—is as much the learned creature of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein as the crude monster of Jewish folk tradition. Ozick’s Judaism is diasporic; her shtetl, the Upper West Side—both cultured and parochial. Her yeshiva, the dual-curriculum Jewish day school—at once ambitious and hidebound.

Ozick’s style distinguishes her as well. Some artists work with bold brushstrokes, and when brushes fail, they use palette knives and hands. Ozick takes a different approach. In her essay “The Seam of the Snail” in Metaphor & Memory, Ozick sets herself apart from those who express themselves brightly and with prodigal variety. She writes self-deprecatingly, “My own way is a thousand times more confined.” Confessing to perfectionism, she calls herself “a kind of human snail,” toiling slowly, and then artfully develops the image: “I measure my life in sentences pressed out, line by line, like the lustrous ooze on the underside of the snail, the snail’s secret open seam, its wound, leaking attar.” She chooses painstaking creation. In a process she figures as wondrous and soul rending, Ozick enamels sentences word by careful word. Note the accretion of detail and glorious rhyme she uses to describe civil servant Ruth Puttermesser. “The truth was that Puttermesser was now a fathomer; she had come to understand the recondite, dim, and secret journey of the City’s money, the tunnels it rolled through, the transmutations, investments, multiplications, squeezings, fattenings and battenings it underwent.” And consider the descriptive mysteries of Petrie’s narrative in Antiquities. He writes of his father’s Egyptian relics, “Many of these pieces, and pieces they are, are instantly identifiable: clay lamps, jugs with handles like ears and spouts like the mouth of a fish, amulets, female figures, and the like, but many are baffling.” Virtuosic at layering words and images, Ozick is also a master of concision—capturing a world of emotion and experience in one short phrase. Petrie recalls his wonder and confusion at a foreign boy at school: “Too many cities were in his tones.” Let others bang out chapters—runways built for plot and speed. Ozick practices the jeweler’s art of cloisonné. This is not to say—as many do of women writers—that Ozick is simply a miniaturist, and that her tales are quiet, and that they are character driven—that is, lacking in suspense. Ozick’s imagination is huge, her work passionate, her inquiry urgent. The philosophical questions in Antiquities become ever more intense as Ozick’s aged narrator grapples with the past. After all, he has limited time left.

Lloyd Petrie knows that he himself is a living relic and, in some ways, the repository of history. He reminisces about old rooms, old lessons, old teachers, old classmates, now deceased or themselves decrepit. His fellow trustees are frail in mind and body. But even as he writes elegiacally of the Temple Academy for Boys, with its Anglican and Anglophilic traditions—chapel, and study of classical languages—Petrie turns to mysteries of the more distant past—the summer of 1880 when his father ran off to Egypt to dig with his cousin William, “then a youthful prodigy of twenty-eight.” This episode becomes a touchstone for Petrie, as do the artifacts his father brought back from Cairo, among them a scarab ring and a stork jug with one emerald eye. Petrie has kept these relics near him since he was a boy, and he considers them now as he puzzles over his father’s life, wondering what they mean and what they are worth.

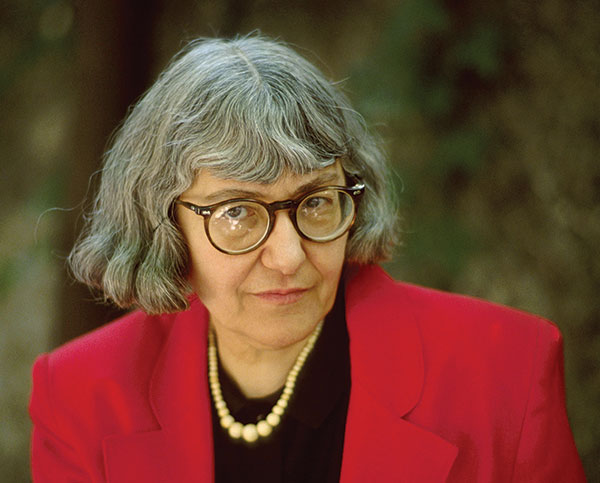

Ozick includes a black-and-white photograph of “Cousin William” as a frontispiece for her fictional Petrie’s narrative. She may be writing fiction, but she makes it clear that her narrator’s famous relation was quite real, the great Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie (1853–1942). There he stands in the undated photo, striding forth with staff in hand, a striking contrast to his obscure unpictured cousin. William is bold and active, supremely confident. He “spoke thrillingly of his plans for the decades ahead: he would search in the Holy Land for all those famed and yet lost and buried cities, among them Lachish and Hinnom and so may storied others. He meant one day, he said, to open the womb of the land that was the mother of true religion.” Empirical and imperial, the Victorian archeologist sought not only to uncover, not only to interpret, but to possess physical evidence for his own beliefs.

In contrast, Ozick’s Petrie is uncertain and faltering. Exhausted by typing, he feels “called upon to lie down, and invariably this leads to a doze.” He is plagued as well by “a state of suffering of the soul . . . a suffering that is more a gnawing paralysis than a conscious pain.” His recollections often sadden and terrify him. Probing ever deeper into memory, he feels he “is in the grip of the void.” The pain of youth, the perils of old age—he is acutely conscious of it all. He breaks off and then attempts again to write. He declares, “I earnestly wish to stop my memoir,” but he does not. The past possesses him.

What does Ozick’s narrator offer us? Susceptibility. Fallibility. Not only a sense of wonder but a sense of fear. He is not a scientist but an acolyte. Not so much a discoverer as a worshipper of hidden things. Ozick writes with unmatched tenderness about such characters—those who love art too much; those who idolize their heroes; those entranced by tradition, religious or literary or both at once. Ruth Puttermesser studies Hebrew grammar in bed where “the permutations of the triple-lettered root elated her.” Lucy, the novelist and convert in “Levitation,”falls in love with the Psalms when she hears her minister father read them from the pulpit, and “all at once she saw how the Psalmist meant her; then and there she became an ancient Hebrew.” Becomes one and yet cannot escape the English literary tradition. “Lucy read only one book—it was Emma—over and over again.” Reading is a blessing and a curse in Ozick’s world, a gateway to heightened emotion and new experience and also a maze of cruel tricks and dead ends.

Ozick appreciates the tragedy of such earnest aesthetes. Indeed, she counts herself among them. She admits that Henry James saturates her first novel Trust. Dangerously in love with the master’s brilliance, his worldliness, and craft, Ozick writes in The Din in the Head: Essays, “I kept on my writing table (a worn old hand-me-down, three feet by one and a half, that I had acquired at age eight) a copy of The Ambassadors, as a kind of talisman.” But Ozick suggests that novels do not always bring the infatuated reader luck, and this complication has become a major theme in Ozick’s later work. Masters mislead followers. Adulation can cause asphyxiation, and Ozick shows how it is done. Bracingly, she explores the opposite case as well. It is possible for the acolyte and the student and the unknown to break free. In The Cannibal Galaxy, a day-school student once ignored becomes a brilliant scholar and forgets her principal’s vaunted curriculum entirely. In Dictation, the secretaries of Henry James and Joseph Conrad begin plotting together secretly. The great Sir William graces the frontispiece of Antiquities, but his unheralded cousin controls the narrative. In a subtle parallel, a portrait of James “once adorned the chapel” of Petrie’s school—but the Academy “gleaned its name” from the family of James’s doomed young cousin Minnie Temple.

If archeologists dig, artists bury. In Ozick’s world, those who decipher the past meet their match in those who encrypt memories. What is art, after all, but encoded meaning? Petrie wonders all his life at what his father meant by running off to Egypt for a summer, but his parents are a mystery. With neat symmetry, Petrie’s son remains mysterious as well, a screenwriter in Hollywood with little interest in his father’s life. But Petrie has secrets of his own—among them two great loves who haunt him still. Long married, he was also long in love with his typist, Miss Margaret Stimmer, “darling Peg,” and so he treats his antique Remington tenderly.

Deeper in the past, Petrie was infatuated with a boy at school—a strange child named Ben-Zion Elefantin. This Jewish boy is undersized and brilliant, exotic in his uncompromising rituals. He resists ordinary friendship, and his oddity becomes the source of Petrie’s fascination. Elefantin seems a world unto himself—embattled and without friends or natural community. It is this resistance that attracts Petrie: the boy’s hard shell, his difficult allegiance to a tradition Petrie does not understand. Elefantin seems a cipher and a relic, the young emblem of a religion older than old. In fact, Elefantin reveals to Petrie that he is not only Jewish but a descendent of an ancient, unnamed sect, distrusted even in the Jewish world. This remnant, reminiscent of the Karaites, broke off before the writing of the Talmud. Why is it important that Elefantin comes from this ancient sect? What is the significance of prerabbinic Judaism here? Petrie cannot tell us. What comes through is the romance of antiquity, a reverence for a religion purer and more elemental than the legalistic Judaism that developed later. A Judaism still based on place—not yet diffused in words.

Elefantin’s history is wonderful and strange, entrancing to Petrie even in old age. For like Ozick’s pagan rabbi, magic civil servant, and enthralled convert, the narrator of Antiquities loves what is foreign and secret. Occult passion is Ozick’s great subject.

The privileged schoolboy’s love for the young Jew is also deeply Jamesian. Like Morgan Moreen, the young boy in James’s “The Pupil,” Elefantin has an uncompromising precocity and purity about him—“no normal boy spoke like a book”—in contrast to his worldly and itinerant family. Like Merton Densher in The Wings of the Dove, Petrie finds himself falling in love with the idea of a person—and ultimately with that person’s memory. Like John Marcher in “The Beast in the Jungle,” Petrie seeks the center, the vital experience in life, “the significant thing.” He wants to capture what he exchanged with Elefantin, what he learned, and what he experienced. Searingly, he writes of the moment that he lay down with the Jewish boy and heard his story:

And now, the two of us, prone on the floor among the nubbles of dust, breathing their spores, I seemed to be breathing his breath. Our bare legs in the twist of my fall had somehow become entangled, and it was as if my skin, or his own, might at any moment catch fire.

A moment of grace, a fleeting instant of unity, intellectual and erotic. Elefantin reveals himself, explaining his heritage as descendent of a forgotten Jewish sect, a tributary cut off from the mainstream. “And so we live on as apparitions,” Elefantin tells Petrie. “And I, Ben-Zion Elefantin, am just such an apparition, am I not?” This moment is the high point of Petrie’s life—but what does it mean? Who or what is the object of his affections? Does he love a boy or an idea? A person or a ghost? Ozick is more interested in crossing over between realms than in drawing clear distinctions. She prefers the question to the answer. Emotion overshadows and often defies explanation. “Only the two of us know,” Petrie declares in his last undated entry.

In this respect, Ozick differs from James, who studies a problem with and for the reader, analyzing it from every angle. For all his psychological complexity, James plots out conflicts leading to conventional revelations—the flaw in a marriage, the machinations of a mistress, the love confessed too late. For all his interiority, James develops social dramas, pitting fully developed characters against each other. He is a diamond cutter, faceting each situation and then turning dilemmas to catch the light. But Ozick is a pearl fisher, freediving. She does not guide the reader closely. Her novels have fewer players—indeed, many have just one. Her best plots are fantastical, her dramas those of the divided self.

Ultimately, Ozick’s protagonists are those who fall in love with literature and cannot get over it. Those who remember and reimagine what they have lost like Rosa in “The Shawl.” Those obsessed with the past like Lloyd Petrie. Those consumed by literary jealousy like Edelshtein in “Envy, or Yiddish in America.” George Eliot famously claimed that she identified most with her aging pedantic character Edward Casaubon—but she weaves Casaubon into a much larger plot, and his point of view is one of many in Middlemarch. Tighter in focus, much of Ozick’s work fixes exclusively on just the sort of vanity Casaubon embodies, its grandiloquence and hopelessness. How small people are, she seems to say, but how desperate, how poignant. We are idolators in grief, in literature, even in our monotheistic hearts. Rosa imbues her shawl with magic. Puttermesser births a female golem from her own imagination. Cloaked in his tallis, the lovesick Rabbi Isaac Kornfeld calls out to a wood nymph, “Creature, see how I am coiled in the snail of this shawl as if in a leaf.” Shawl, snail, leaf. Emblems of tradition, art, and nature. Symbols in Ozick’s personal cosmography as well. The shawl, a relic, prayer covering, and shroud. The snail, the slow insignia of the writer’s work. The leaf, art’s antidote, a reproach to bookishness.

Ozick plays with each of these elements in Antiquities as Petrie interrogates the past. She writes about grief. She writes about mystery. She writes about the search for what is holy, what is significant, and what is real. And she writes about creativity, brilliantly marrying the problem of old age with the problem of art, as Ozick’s frail trustee asks the artist’s question. How can I capture experience? How can I hold time fast even as time slips away from me? This novel is brief, but its questions are fundamental. The narrator’s life is now confined, but his desire, wonder, and regret are limitless.

Suggested Reading

Cynthia Ozick: Or, Immortality

Ozick is as marvelously demanding, harrumphing, and uncompromising as she has always been.

A Harem of Translators

Singer insisted that all foreign-language translations of his work be based on the English versions. And most of them were done by young women who closer to typist-editors than true translators.

Going Public

The Jewish Jane Austen, or better?

Lost in Translation

The novelist Jonathan Rosen has written evocatively of the parallels between rabbinic literature and the World Wide Web: “When I look at a page of Talmud and see all those texts tucked intimately and intrusively onto the same page, like immigrant children sharing a single bed, I do think of the interrupting, jumbled culture of the Internet.” Rosen’s insight is…

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In