A Complex Network of Pipes

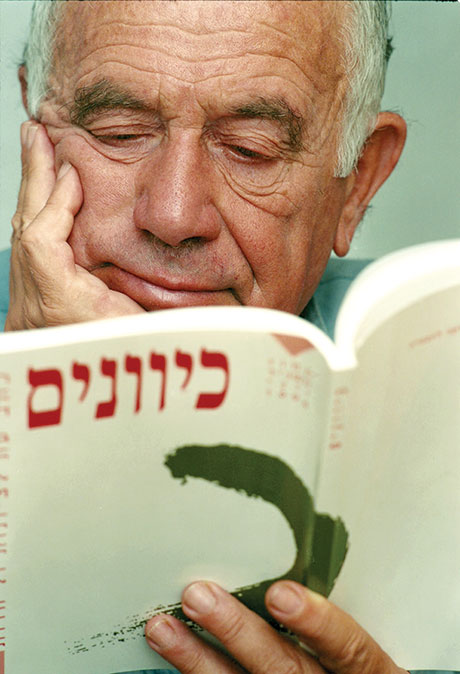

While browsing in Yehuda Amichai’s collected Hebrew verse in preparation for writing this review, I came across a poem, previously unknown to me, that stirred a pang of memory. Since it isn’t one of the hundreds of poems included in The Poetry of Yehuda Amichai by its editor Robert Alter, I’ll translate it here:

On the day my daughter was born no one died.

Over the entrance to the hospital it said:

“Priests may visit today.”

It was the longest day of the year.

In my joy

I drove with a friend to the hills at Sha’ar ha-Gai.

We saw a pine tree, sick and bare but full of cones.

Tsvi said a tree about to die produced more cones

than one assured of living. I said to him, “You’ve

just produced

a poem without knowing it. Man of exact science

though you are,

that was a poem.” He answered me, “And you,

though you

may be a man of dreams, have just produced a

baby girl equipped

with every last, exact appurtenance that’s needed

for a life.”

My memory was of the many hikes I, too, took with Tsvi Sachs, who was my friend as he was Amichai’s and whose family and mine were close in those years. (Amichai’s daughter Emanuella was born in the late 1970s.) Tsvi was a professor of botany at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and a renowned figure in his field. It was always an education to be with him in nature. A few months ago, unable to attend a memorial lecture in his honor, I wrote his widow Laura: “To this day, I sometimes find myself looking at a plant, asking myself why it’s growing this way or that, and wondering what Tsvi would say about it. If plants had minds, no one could read them like he could.”

I suppose the hospital was Bikur Cholim. An institution bordering on Jerusalem’s most heavily religious neighborhoods, it would have taken the trouble to inform kohanim, members of the priestly caste forbidden by Jewish law to be in the vicinity of a corpse, that they were free to enter on that June 21 when Amichai drove with Tsvi Sachs to Sha’ar ha-Gai, “The Gate of the Ravine,” where the Judean lowlands meet the Jerusalem hills. There’s a lovely humor in the poem’s switch of roles, its scientist speaking like a poet and its poet fathering a work of scientific perfection. But in fact, I imagine that the scientist was speaking like a scientist. All Tsvi probably meant to say was that the tree’s imminent death triggered the release of plant hormones that maximized its reproductive forces in a last effort to propagate itself. It took a poet to see a poem in this.

And that, when one thinks of Yehuda Amichai, is a large part of his greatness. The man saw poetry everywhere. If anyone spoke it, it was he. You couldn’t know him without being struck by the casual way in which original and sometimes startling metaphors dropped from him in ordinary conversation, spontaneously occasioned by something that you and he might be looking at or talking about. It wasn’t done for effect. It was just the way his mind worked. His thought was habitually associational. One thing made him think of another and what it made him think of was generally something that would not have occurred to anyone else.

Of course, metaphors are not what make a poem a poem. A poem can have no metaphors at all, and, conversely, a passage of prose can have many. Poetry differs from prose because of its sound: meter, rhythm, rhyme, echo, alliteration. Prose can have some of these things, too, but it ceases to be prose when they are heightened to a certain level, just as a walk speeded up to a certain point becomes a run. It’s a matter of music.

Amichai’s poetry has its music, but it is for the most part background music. He abandoned the occasional use of rhyme, regular meter, and driving rhythms early in his career, after which his lines took on a conversational tone devoid of special sound effects. I can’t think of another major poet of our or any other age whose poetry depends so much—at times, it would seem, almost exclusively—on figurative language.

Take—I’m still browsing—his poem “I Am Invited to Life,” translated by Alter:

I am invited to life. But

I see that my hosts show signs of fatigue

and impatience.

Trees sway, clouds fall ever more

silent. Mountains move

from place to place, the heavens gape.

And in the nights, winds move around

objects uneasily, smoke, people, lights.

I sign the guestbook

of God: I was, I lingered,

it was good, I enjoyed, I was guilty, I

betrayed,

I was impressed by the reception

in this world.

This is a poem that playfully hinges on the metaphor of life as the giver of a reception or cocktail party by whose end the poet has bored the other guests, the elements of nature, to distraction. They sway with too much to drink, yawn (the literal meaning of m’fahakim, translated by Alter as “gape”), moodily withdraw, wander aimlessly around the room, even take to moving around its furniture. And yet the poet has had a good time. He is impressed by the grand affair the world has staged for him, even though the world has not been in the least impressed by him.

Alter’s translation is fluent. It isn’t its fault that it can’t reproduce the levity of the internal rhyme in “I was, I lingered” (hayiti, shahiti) or fully convey the religious allusions in “I was guilty, I betrayed” (ashamti, bagadeti) and “in this world” (ba-olam ha-zeh)—the first of these alludes to the confessional in the Yom Kippur prayer that begins ashamnu, bagadnu, “we have been guilty, we have betrayed,” the second to the rabbinic contrast of “this world” (ha-olam ha-zeh) with “the next world” (ha-olam ha-ba). If one wished to press a point, one might invoke the well-known

saying in Ethics of the Fathers, “This world is like a parlor before the world to come; prepare yourself in the parlor that you may enter the banquet hall.” The cocktails will be followed by a formal dinner in another room—but to that, it seems, the poet is too nonchalant about his life and its guilts to have been invited.

Amichai was a deeply Jewish poet. His Orthodox education and upbringing in Germany before emigrating with his family to Palestine at the age of 12 in 1936 (he died in Jerusalem in the year 2000) left their permanent mark on him, though his adult life was lived as a non-observant Jew in secular Israeli society. This society regarded him as its own quintessential expression. He lived and wrote about its wars and tragic conflicts; he shared its appetite for life and its love of its land; his irreverent humor struck a chord in it. And yet he also had an ironic detachment from it, a distance that came partly from being steeped in a Jewish tradition that was foreign to it. He knew, as it didn’t, what had been lost. He had a yearning for the sacred whose pieties and pretensions he liked to tease. “‘What kind of man are you?’ people ask me,” begins a five-stanza poem of his translated by Chana Bloch. And he replies:

I am a man with a complex network of pipes in

my soul,

sophisticated machineries of emotion

and a precisely-monitored memory system

of the late twentieth century,

but with an old body from ancient days

and a God more obsolete even than my body.

This stanza, too, is controlled by an extended metaphor. But what has suggested it? And why, after the second stanza further explores the idea of “an old body from ancient days” (“I am a man for the surface of the earth. / Deep places, pits and holes in the ground / make me nervous. Tall buildings / and mountaintops terrify me”), does the third stanza switch to an entirely new set of images?

I am not like a piercing fork

nor a cutting knife nor a scooping spoon

nor a flat, wily spatula that sneaks in from

underneath.

At most I’m a heavy and clumsy pestle

that mashes good and evil together

for the sake of a little flavor,

a little fragrance.

“Guideposts don’t tell me where to go,” continues the first line of the fourth stanza in Bloch’s translation. Actually, “arrows,” the literal meaning of chitzim, the word used by Amichai, would have been, as we shall see, better. The rest of this stanza and the last one read:

I conduct my business quietly, diligently,

as if carrying out a long will that began to be written

the moment I was born.

Now I am standing on the sidewalk,

weary, leaning on a parking meter.

I can stand here for free, my own man.

I’m not a car. I’m a human being, a man-god, a

god-man

whose days are numbered. Hallelujah.

And only now, having reached the poem’s end, can we reconstruct its chain of associations. These start with the parking meter. Stopping to rest against it in a Jerusalem street, the poet has thought to his amusement, “If I were a car I’d have to pay for this—but I’m not.” This causes him to ask, more seriously, just what the difference between a human being and a machine is and to come to the first stanza’s paradoxical conclusion that even if the mind or “soul” can be analyzed in mechanical terms as a technologically advanced arrangement of neurons and synapses, the more primitive body remains a spiritual organism in need of God. It is in the poet’s body—described as conservatively earth-hugging in stanza two and as the transmitter of ancestral imperatives in stanza four—that his humanity most resides.

But why the shift of imagery in stanza three? Here, I suggest, the associational chain starts with “arrows.” The street the poet is standing in has signs, whether to indicate that it is one-way or to designate turning lanes at a traffic light, and these cause him to think in the first line of the fourth stanza: “And because I am a human being, I will not let myself be directed like a car in traffic.” But arrows not only direct. They also pierce, and the next association, taking us back to the third stanza, is with other piercing objects like knives and forks. The thought of these leads to the thought of kitchen utensils in general and from there to the whimsical question: “If I were a kitchen utensil, what kind of kitchen utensil would I be?” To which the answer is: not the kind that neatly divides things up or separates them out into categories that form the basis for hard-and-fast judgments, but the kind that nonjudgmentally preserves their unity, which is more confusing but far richer than anything considered separate from or in opposition to everything else.

And all this looping back and forth of ideas and images, culminating in the fifth stanza’s celebration of the ultimate, although perhaps doomed, unity of the human and divine (for the poem’s ambiguous last line makes us ask just whose days are numbered, the poet’s alone or all humanity’s), has originated in a chance encounter with a parking meter! Thought leads to thought, metaphor to metaphor. And it leads us to the thought that metaphor, though not a necessary condition for poetry, can sometimes be its main attribute.

For what, broadly speaking, is a metaphor, called by Amichai in an interview with the Israeli American literary critic Chana Kronfeld (as cited in her recently published The Full Severity of Compassion: The Poetry of Yehuda Amichai), “the greatest invention of mankind, more than the wheel and the computer”? It is a link between distant phenomena, just as a rhyme is a link between distant words and a metric foot a link between distant lines. Seemingly unrelated items are brought into contact; discrete objects or ideas are set side by side. Each time Amichai says something like, “Like a newspaper clinging to a fence in a blowing wind, / so my soul clings to me. / If the winds stops, / my soul will fall” (from “A Great War Is Being Fought,” translated by

Kronfeld); or “Like an old windmill, / two hands always raised to shout to the sky / and two lowered to prepare sandwiches” (“To the Mother,” Robert Alter); or “The echo of a great love is like / the echo of a huge dog’s barking / in an empty Jerusalem house / marked for demolition” (“71,” from Time, Ted Hughes); or “Like a knife peeling a round fruit, I sense / the motion of time round and round” (“Herodion,” Leon Wieseltier), he heightens our awareness of the potential interconnectedness of all things. Not clumsily like a pestle, but with the precision of a needle, a good metaphor stitches together fragments of the world that have never been joined before.

Metaphors humanize the world, just as did primitive religion when it personified nature and anthropomorphized the gods. They commit the “pathetic fallacy,” scorned by science (although the only pathetic thing about it is not realizing that when John Ruskin coined the phrase, he was using “pathetic” to mean “feeling-full,” not “pitiful”), of filling the world with human thoughts and emotions. There is a passage toward the end of Amichai’s great early poem “The Elegy for the Lost Child” that is also not in Alter’s anthology. In it, the search for a small boy who has gone missing in the Israeli countryside is juxtaposed with a love affair. (Love and death were Amichai’s two great themes.) A man and a woman are in bed in their attic room:

Last winter’s rains lived on even in summer.

The trees spoke loudly in earth’s sleep. Tin voices rang

in the stirring wind. We lay together. I rose to go.

The eyes of the woman I loved

were wide-open with fear. She propped herself up

in the bed on her elbows. The sheet was the white

of Judgment Day and she wouldn’t remain

in the building alone and left for the world

that began with the stairs by the door.

But the child remained and began to resemble

the mountains and winds and trunks of the olive trees.

As in a family likeness: the face of the youth who fell

in the Negev recurs in the face of the cousin

born in New York. A mountain the Arava broke

in two

appears in the broken look of a friend.

It was in the Negev, whose Arava Valley is part of the Syro-African Rift, that Amichai fought as an infantry soldier in Israel’s 1948 War of Independence. Perhaps the friend is the parent of a boy killed in battle. It is the dry Israeli summer, not long before Yom Kippur (on which it is customary to wear white), though the roots of the trees still drink old rainwater. The wind ripples in the trees and rattles the tin roof over the attic. The poet rises from love’s bed to join the search party for the child. The young woman is frightened. But the child, found dead at the poem’s end, is with the elements amid which it came to grief.

One thinks of Dylan Thomas’s “A Refusal to Mourn the Death, by Fire, of a Child in London” and its vow to “not murder / The mankind of her going with a grave truth / Nor blaspheme down the stations of the breath / With any further / Elegy of innocence and youth.” Amichai, who once journeyed to visit Thomas’s grave in Wales and wrote about it, surely knew the poem; the word for “elegy” in his title is the loan word elegya. His own poem does not refuse to mourn. What it refuses to do is turn its child into a symbol. “London’s daughter / robed in the long friends, / The grains beyond age, the dark veins of her mother” is made to stand for us all. Thomas’s poem ends with the line—a grave truth if ever there was one!—“After the first death, there is no other.” Amichai’s elegy ends with the discovery of the dead child, or perhaps with its funeral.

But the child died at night,

clean and neatly combed. Groomed and licked by the tongues

of God and the night. “When we got here, there was still light.

Now it’s dark.” Clean and white like a sheet

of stationary in a sealed envelope, hymned

by the Psalms of the lands of the dead.

Some went on searching, whether for a pain

to suit their tears or a joy to suit their laughter.

Not everything suits everything. Even the hands

are another body’s. But to us it seemed

that something had befallen. We heard a clink like

a fallen coin’s. We stood. We walked about. We bent to look.

We found nothing and we went our way, each his own way.

A joy to suit their laughter? At a child’s death? Of course not. But the searchers who have told the media, or curious bystanders, that it was still light out when they reached the place where they later, in darkness, found the child’s body (perhaps “clean and neatly combed” because it has died in a sudden accident, so that it seems “licked by the tongues of God and the night”)—the searchers who have searched not only for the child but also, unknowingly, for something in themselves—these searchers will, like the rest of us, go on living their lives looking for the right outward correlatives—the right metaphors, if you will—for their inner states of being. And how hard it is to find them when “not everything suits everything” and even a pair of hands can be attached to the wrong body!

The lost child’s death, despite its tantalizing intimation of bearing some message, some light in the darkness, stands for nothing; after the first death, there is every other. The “family likeness” of metaphor is relationship, not identity. Kronfeld, in discussing Amichai’s use of metaphor, speaks of its “living on the hyphen” in the sense of “never eras[ing] the disparate domains that it brings together, even while it strives to make the transient, limited space in between them as existentially meaningful as it can possibly be.” This is a good point. (There are many good points in Kronfeld’s book, which are unfortunately blunted by her frequent resort to the dulling discourse of academic literary theory.)

It is up to Amichai’s readers to enter this “in between” and explore its possibilities. The motion of time may be infinitely circular, but it is also cruelly finite, because the knife in “Herodion” will soon have finished peeling the fruit that will then be eaten. The word for soul in “A Great War Is

Being Fought,” Kronfeld points out, is nefesh, while the Hebrew word for wind, ru’ach, also means spirit, so that in terms of medieval Jewish philosophy’s tripartite division of the soul into nefesh, neshama, and ru’ach, the biological soul, the emotional soul, and the mental-spiritual soul, the newspaper-nefesh, the life force clinging to the body, is kept there only by the pressure of the spirit. The apparent simplicity of Amichai’s metaphors can be deceptive.

Because its music is so muted, Amichai’s poetry is relatively easy to translate. There is no disrespect for the gifted translators in The Poetry of Yehuda Amichai (besides those already mentioned, these include Glenda Abramson, Assia Gutmann, Barbara and Benjamin Harshav, Stephen Mitchell, Ruth Nevo, Tudor Parfitt, and Harold Schimmel) in saying that the challenges that faced them were on the whole fewer than those presented by other prominent modern poets. “On the whole,” however, does not mean always. Preserving the natural flow of the verse while finding the best equivalent for a Hebrew word or phrase that has no exact counterpart in English, conveying a facet of Israeli life or society immediately recognizable to the Hebrew but not the English reader, coping with Amichai’s often veiled allusions to Jewish tradition—all these things pose problems. Nor can one solve them, as one often can in translating prose, by smuggling explanations into the text, since the tightness of good poetry rarely allows for such stretching. In dealing with these difficulties, the translations in Alter’s volume, most of them previously published, have done their job well without attempting to do the impossible. They read smoothly and hardly ever make one wince by going off-key or stepping on a poem’s toes. Although the English Amichai of this volume may not in every case be as fully nuanced as the Hebrew one, he is an accurate enough facsimile. Alter has chosen wisely and seen to it that English readers have gotten the real thing.

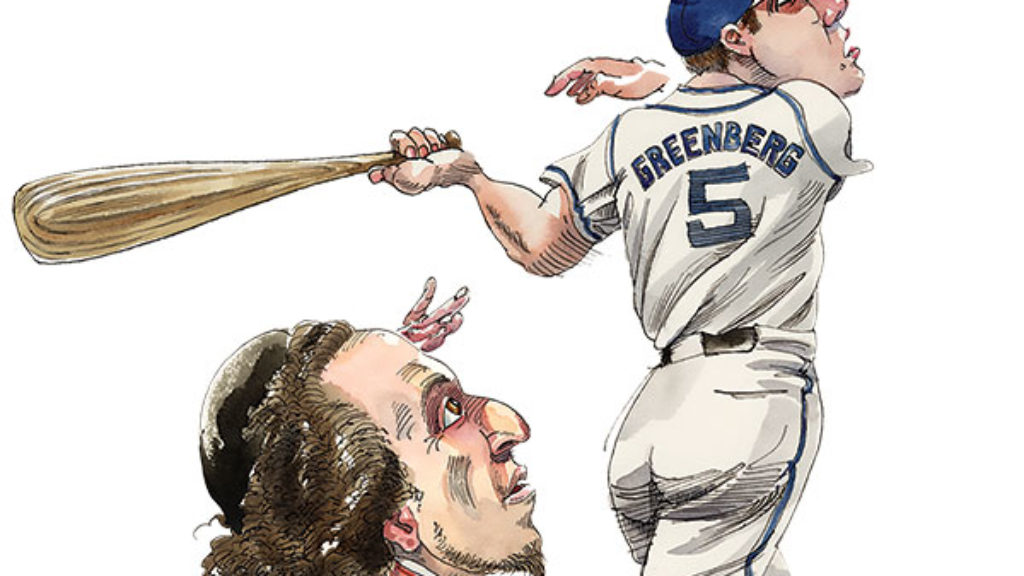

Amichai was a prolific poet. It is impressive how high a percentage of his poems are very good ones—considerably higher, I would say, than among most poets of stature. And a poet of stature he is. He ranks with the major Hebrew poets of antiquity such as Yosi ben Yosi and Hakalir, with such medieval greats as Halevi and Hanagid (whom he particularly admired; “On the Day My Daughter Was Born” has a distinctly Hanagidish flavor), with the best the 20th century can boast of. It is fitting that he and Bialik should have opened and closed this century between them, like parentheses that can contain any number of other names. But that, of course, is only a metaphor.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Symbol Catcher

My friends and I took for granted that the connection between the cards and the players they represented wasn’t just arbitrary.

Swimming in an Inky Sea

Ilana Kurshan, a hyper-literary, ideologically egalitarian, hopeless romantic (in her words), doesn’t fit the typical profile of a Daf Yomi participant.

Du Bois, the Warsaw Ghetto, and a Priestly Blessing

When the editors at Jewish Life asked the venerable civil rights leader W. E. B. Du Bois to speak about the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, they had no idea that it would lead to a priestly blessing.

Workday Jews

In their respective books, Chad Alan Goldberg and Eliyahu Stern address the question of whether the Jews are the quintessentially modern people or a people who came to modernity late and with a sudden shock. They reach very different conclusions.

gershonhepner

IS GOD OBSOLETE OR MERELY ARCHAIC?

Saying God is altogether obsolete,

as once poetically Yehuda Amichai declared,

isn't very controversial, the conceit

today is by a large majority of people shared,

including those whose faith was formerly Mosaic,

Jews now completely stereotypical in this stampede.

I'm not, for although I would say that He's archaic,

God still succeeds in satisfying a most basic need,

to be connected with the past, and to the laws

that in the past connected Jews to Him, “Only connect'”

a mantra that's not obsolete, His major cause,

which, though it seems somewhat archaic, we must still respect.

maieutic

Hey--a significant amount of this is a riff on Bob Dylan--esp "Subterranean Homesick Blues" but other songs too that Dylan was riffing on--is that what they call a mile-en-abyme"?!